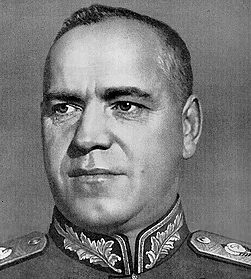

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov (Russian: Георгий Константинович Жуков; listen (help·info); 1 December 1896 – 18 June 1974) was a Soviet general and Marshal of the Soviet Union. He also served as Chief of the General Staff, Minister of Defence, and was a member of the Presidium of the Communist Party (later Politburo). During the Second World War, Zhukov oversaw some of the Red Army‘s most decisive victories.

Born to a poor peasant family from central Russia, Zhukov was conscripted into the Imperial Russian Army and fought in the First World War. He served in the Red Army during the Russian Civil War. Gradually rising through the ranks, by 1939 Zhukov had been given command of an army group and won a decisive battle over Japanese forces at Khalkhin Gol, for which he won the first of his four Hero of the Soviet Union awards. In February 1941, Zhukov was appointed as chief of the Red Army’s General Staff.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Zhukov lost his position as chief of the general staff. Subsequently, he organized the defense of Leningrad, Moscow, and Stalingrad. He participated in planning several major offensives, including the Battle of Kursk, and Operation Bagration. In 1945, Zhukov commanded the 1st Belorussian Front; he took part in the Vistula–Oder Offensive, and the Battle of Berlin, which resulted in the defeat of Nazi Germany, and the end of the war in Europe. In recognition of Zhukov’s role in the war, he was chosen to accept the German Instrument of Surrender, and inspect the Moscow Victory Parade of 1945.

After the war, Zhukov’s success and popularity caused Joseph Stalin to see him as a potential threat. Stalin stripped him of his positions and relegated him to military commands of little strategic significance. After Stalin’s death in 1953, Zhukov supported Nikita Khrushchev‘s bid for Soviet leadership. In 1955, he was appointed as Defence Minister and made a member of the Presidium. In 1957 Zhukov lost favour again and was forced to retire. He never returned to a position of influence, and died in 1974.

Contents

- 1Early life and career

- 2Eastern Front of World War II

- 3Post-war service

- 4After Stalin

- 5Retirement

- 6Death

- 7Family

- 8Legacy

- 9In popular culture

- 10Decorations

- 11References

- 12Further reading

- 13External links

Early life and career[edit source]

Zhukov was born into a poverty-stricken peasant family of Russian[1] ethnicity in Strelkovka, Maloyaroslavsky, Kaluga Governorate in western Russia.[2] His father Konstantin, who had been orphaned at age two and then adopted by Anuska Zhukova, was a cobbler.[3] His mother Ustin’ya was a peasant laborer. Zhukov was said to resemble his mother, and he believed he inherited his physical strength from her; Ustin’ya was reportedly able to accomplish demanding tasks such as carrying 200-pound sacks of grain over long distances.[3] In an era when most members of Russia’s poor and working classes completed only two years of schooling, Zhukov completed the three-year primary education course at his hometown school.[3] He was then apprenticed to his mother’s brother Mikhail as a furrier in Moscow.[4]

While working for his uncle, Zhukov supplemented his education by reading with his cousin Alexander on a wide range of topics, including the Russian language, German language, science, geography, and mathematics.[4] In addition, he enrolled in a night school, where he completed courses as the work in his uncle’s shop permitted.[4] He completed his apprenticeship in 1914 and established his own business, which included three young employees under his leadership.[4]

World War I[edit source]

Non-commissioned officer Georgy Zhukov, Russian Imperial army, 1916

In 1915, Zhukov was conscripted into the Imperial Russian Army, where he served in the 10th Dragoon Novgorod Regiment, and was wounded in action against the Germans at Kharkiv. During World War I, Zhukov was awarded the Cross of St. George twice, and promoted to the rank of non-commissioned officer for his bravery in battle.

He joined the Bolshevik Party after the 1917 October Revolution; in party circles his background of poverty became a significant asset. After recovering from a serious case of typhus, he fought in the Russian Civil War, serving in the Second Cavalry Brigade, commanded by Semyon Timoshenko, which was later absorbed into the 1st Cavalry Army, led by Semyon Budyonny. He completed a cavalry training course for officers in 1920 and received his commission as an officer. He received the Order of the Red Banner for his part in subduing the Tambov Rebellion in 1921.[5]

Interwar period[edit source]

Zhukov as a regimental commander, 1920sGraduates of the Leningrad Higher Cavalry School 1924/25

Sitting in the second row (right to left): 1. Bagramyan, 3. Yeremenko. Standing in the third row (right to left): 1. Zhukov, 5. Rokossovsky.

Zhukov quickly advanced through the ranks as the commander of a cavalry troop and squadron, and deputy commander of a cavalry regiment. At the end of May 1923, he was appointed commander of the 39th Cavalry Regiment.[6] In 1924, he entered the Higher School of Cavalry,[7] from which he graduated the next year, returning afterward to command the same regiment.[8] He attended the Frunze Military Academy beginning in 1929, and graduated in 1930.[9]

In May 1930, Zhukov became commander of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade of the 7th Cavalry Division.[10] In February 1931, he was appointed as the Assistant Inspector of Cavalry for the Red Army.[11]

In May 1933, Zhukov was appointed commander of the 4th Cavalry Division.[11] His career was accelerated by the Great Purge, when thousands of officers were arrested and shot, but those associated with the First Cavalry Army were protected. In 1937, Zhukov became commander of first the 3rd Cavalry Corps, and later the 6th Cavalry Corps.[12] In 1938, he became deputy cavalry commander of the Belorussian Military District.[13]

Khalkhin Gol[edit source]

In 1938, Zhukov was directed to command the First Soviet Mongolian Army Group, and saw action against Japan’s Kwantung Army on the border between the Mongolian People’s Republic and the Japanese-controlled state of Manchukuo. The Soviet–Japanese Border Wars lasted from 1938 to 1939. What began as a border skirmish rapidly escalated into a full-scale war, with the Japanese pushing forward with an estimated 80,000 troops, 180 tanks and 450 aircraft.

These events led to the strategically decisive battle of Khalkhin Gol. Zhukov requested major reinforcements, and on 20 August 1939, his Soviet offensive commenced. After a massive artillery barrage, nearly 500 BT-5 and BT-7 tanks advanced,[14] supported by over 500 fighters and bombers.[15] This was the Soviet Air Force‘s first fighter-bomber operation.[16]

The offensive first appeared to be a typical conventional frontal attack. However, two tank brigades were initially held back and then ordered to advance around on both flanks, supported by motorized artillery, infantry, and other tanks. This daring and successful maneuver encircled the Japanese 6th Army and captured the enemy’s vulnerable rear supply areas. By 31 August, the Japanese had been cleared from the disputed border, leaving the Soviets clearly victorious.[16]

This campaign had significance beyond the immediate tactical and local outcome. Zhukov demonstrated and tested the techniques later used against the Germans in the Eastern Front of the Second World War. His innovations included the deployment of underwater bridges, and improving the cohesion and battle-effectiveness of inexperienced units by adding a few experienced, battle-hardened troops to bolster morale and overall training.[17]

Evaluation of the problems inherent in the performance of the BT tanks led to the replacement of their fire-prone petrol (gasoline) engines with diesel engines. This battle provided valuable practical knowledge that was essential to the Soviet success in development of the T-34 medium tank used in World War II. After this campaign, veterans were transferred to untested units, to better spread the benefits of their battle experience.[18]

For his victory, Zhukov was declared a Hero of the Soviet Union. However, the campaign—and especially Zhukov’s pioneering use of tanks—remained little known outside the Soviet Union. Zhukov considered Khalkhin Gol to be invaluable preparation for conducting operations during the Second World War.[19] In May 1940, Zhukov became an army general, making him one of the eight high-ranking Red Army officers.

Pre-war military exercises[edit source]

Zhukov and Semyon Timoshenko in 1940

In the autumn of 1940, Zhukov started preparing plans for the military exercise concerning the defence of the Western border of the Soviet Union. It had been pushed further to the west after the Soviet Union annexed eastern Poland and the Baltic republics.[20] In his memoirs, Zhukov reports that in this exercise, he commanded the Western or Blue forces—the supposed invasion troops—and his opponent was Colonel General Dmitry Pavlov, the commander of the Eastern or Red forces –the supposed Soviet troops. He noted that Blue had 60 divisions, while Red had 50 divisions. Zhukov describes the exercise as being similar to events that later took place during the German invasion.[21]

Russian historian Bobylev noted that the details of the exercises were reported differently by the various participants who published memoirs.[22] He said that there were two exercises; one from 2 to 6 January 1941, for the North-West direction; another from 8 to 11 January, for the South-West direction.[22] During the first, Western forces attacked Eastern forces on 15 July, but the Eastern forces counterattacked and, by 1 August, reached the original border.[22]

At the time, the Eastern forces had a numerical advantage: 51 infantry division against 41; 8,811 tanks against 3,512 – with the exception of anti-tank guns.[22] Bobylev describes how by the end of the exercise, the Eastern forces did not manage to surround and destroy the Western forces. In their turn, the Western forces threatened to surround the Eastern forces.[22] The same historian reported that the second game was won by the Easterners, meaning that on the whole, both games were won by the side commanded by Zhukov.[22] However, he noted that the games had a serious disadvantage since they did not consider an initial attack by Western forces, but only an attack by Eastern forces from the initial border.[22]

According to Marshal Aleksandr Vasilevsky, the war-game defeat of Pavlov’s Red Troops against Zhukov was not widely known. The victory of Zhukov’s Red Troops was widely publicized, which created a popular illusion of easy success for a preemptive offensive.[23] On 1 February 1941, Zhukov became chief of the Red Army’s General Staff.[24] He was also elected a candidate member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union In February 1941, and was appointed a Deputy People’s Commissar for Defence in March.

Soviet offensive controversy[edit source]

See also: Soviet offensive plans controversy

From 2 February 1941, as the chief of the general staff, and Deputy Minister of Defense, Zhukov was said to take part in drawing up the “Strategic plan for deployment of the forces of the Soviet Union in the event of war with Germany and its allies.”[25] The plan was completed no later than 15 May 1941, according to a dated document found in the Soviet archives after they were declassified in the 1990s. Some researchers, such as Victor Suvorov, have theorized that on 14 May, Soviet People’s Commissar of Defense Semyon Timoshenko and General Zhukov presented these plans to Stalin for a preemptive attack against Germany through Southern Poland.

Soviet forces would occupy the Vistula Border and continue to Katowice or even Berlin—should the main German armies retreat—or the Baltic coast, should German forces not retreat and be forced to protect Poland and East Prussia. The attacking Soviets were supposed to reach Siedlce, Dęblin, and then capture Warsaw before penetrating toward the southwest and imposing final defeat at Lublin.[26]

Historians do not have the original documents that could verify the existence of such a plan, and there is no evidence that Stalin accepted it. In a transcript of an interview on 26 May 1965, Zhukov said that Stalin did not approve the plan. But Zhukov did not clarify whether execution was attempted. As of 1999, no other approved plan for a Soviet attack had been found.[27]

On 10 June 1941, Zhukov sent a message to the Military Council of the Kiev Special Military District, after someone, most likely the commander of the Kiev district, Mikhail Kirponos, had ordered troops on the border to occupy forward positions. Zhukov ordered: “Such action could provoke the Germans into armed confrontation fraught with all sorts of consequences. Revoke this order immediately and report who, specifically, gave such an unauthorised order.” On 11 June, he sent a telegram saying that his immediate superior, Timoshenko, had ordered that they were to report back by 16 June confirming that the troops had been withdrawn from their forward positions.” According to the historian David E. Murphy, “the action by Timoshenko and Zhukov must have been initiated at the request of Stalin.”[28]

David Glantz and Jonathan House, American scholars of the Red Army, argue that “the Soviet Union was not ready for war in June 1941, nor did it intend, as some have contended, to launch a preventative war.”[29] Gerhard Weinberg, a scholar of Nazi foreign policy, supports their view, arguing that Adolf Hitler‘s decision to launch Operation Barbarossa was not because of a sense of urgent foreboding, but rather from a “purposeful determination” and he had started his planning for the invasion well in advance of the summer of 1941[30]

Eastern Front of World War II[edit source]

On 22 June 1941, Germany launched Operation Barbarossa, an invasion of the Soviet Union. On the same day, Zhukov responded by signing the “Directive of Peoples’ Commissariat of Defence No. 3”, which ordered an all-out counteroffensive by Red Army forces. He commanded the troops to “encircle and destroy [the] enemy grouping near Suwałki and to seize the Suwałki region by the evening of 24 June” and “to encircle and destroy the enemy grouping invading in [the] Vladimir-Volynia and Brody direction” and even “to seize the Lublin region by the evening of 24 June”.[31]

Despite numerical superiority, this manoeuvre failed and disorganized Red Army units were destroyed by the Wehrmacht.[32] Zhukov subsequently claimed that he was forced to sign the document by Joseph Stalin, despite the reservations that he raised.[33] This document was supposedly written by Aleksandr Vasilevsky.[34]

When Stalin arrived unannounced at command headquarters on 29 June, demanding to know why he was not being told what was happening at the front, Zhukov courageously told him: “Comrade Stalin, our duty is first of all to help the front commanders and only then to inform you.” But when he had to admit that they lost contact with the front commanders in Belarus, Stalin lost his temper and called him “useless”.[35]

On 29 July, Zhukov was removed from his post of chief of the general staff. In his memoirs he gives his suggested abandoning of Kiev to avoid an encirclement as a reason for it.[36] On the next day the decision was made official and he was appointed the commander of the Reserve Front.[36] There he oversaw the Yelnya Offensive, delivering the Red Army’s first victory over the Germans. On 10 September, Zhukov was made the commander of the Leningrad Front.[37] There he oversaw the defense of the city.

On 6 October, Zhukov was appointed the representative of Stavka for the Reserve and Western Fronts.[38] On 10 October, those fronts were merged into the Western Front under Zhukov’s command.[39] This front then participated in the Battle of Moscow and several Battles of Rzhev.

In late August 1942, Zhukov was made deputy commander in chief and sent to the southwestern front to take charge of the defence of Stalingrad.[40] He and Vasilevsky later planned the Stalingrad counteroffensive.[41] In November, Zhukov was sent to coordinate the Western Front and the Kalinin Front during Operation Mars. In January 1943, he—together with Kliment Voroshilov—coordinated the actions of the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts and the Baltic Fleet in Operation Iskra.[42] On January 18, 1943, Zhukov was promoted to Marshal of the Soviet Union.[43]Zhukov and Ivan Konev during the Battle of Kursk, 1943

Zhukov was a Stavka coordinator at the battle of Kursk in July 1943. He was considered the main architect of the Soviet victory together with Vasilevsky.[44] According to Zhukov’s memoirs, he played a central role in the planning of the battle and the hugely successful offensive that followed. Commander of the Central Front Konstantin Rokossovsky, said, however, that the planning and decisions for the Battle of Kursk were made without Zhukov, that he only arrived just before the battle, made no decisions and left soon afterwards, and that Zhukov exaggerated his role.[45] A sense of the nature of the beginning of Rokossovsky’s famous World War II rivalry with Zhukov can be gathered from reading Rokossovsky’s comments in an official report on Zhukov’s character:[46]

Has a strong will. Decisive and firm. Often demonstrates initiative and skillfully applies it. Disciplined. Demanding and persistent in his demands. A somewhat ungracious and not sufficiently sympathetic person. Rather stubborn. Painfully proud. In professional terms well trained. Broadly experienced as a military leader… Absolutely cannot be used in staff or teaching jobs because constitutionally he hates them.

From 12 February 1944, Zhukov coordinated the actions of the 1st Ukrainian and 2nd Ukrainian Fronts.[47] On 1 March, Zhukov was appointed the commander of the 1st Ukrainian Front until early May following the ambush of Nikolai Vatutin, its commander, by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army near Ostroh.[48] During the Soviet offensive Operation Bagration, Zhukov coordinated the 1st Belorussian and 2nd Belorussian Fronts, later the 1st Ukrainian Front as well.[49] On 23 August, Zhukov was sent to the 3rd Ukrainian Front to prepare for the advance into Bulgaria.[50]Zhukov accepting the German Instrument of Surrender in Berlin, 1945

On 16 November, he became commander of the 1st Belorussian Front which took part in the Vistula–Oder Offensive and the battle of Berlin.[51] He called on his troops to “remember our brothers and sisters, our mothers and fathers, our wives and children tortured to death by [the] Germans … We shall exact a brutal revenge for everything.” More than 20 million Soviet soldiers and civilians died as a result of the war. In a reprise of atrocities committed by German soldiers against Soviet civilians in the eastward advance into Soviet territory during Operation Barbarossa, the westward march by Soviet forces was marked by brutality towards German civilians, which included looting, burning and systematic rapes.[52]

Zhukov was chosen to personally accept the German Instrument of Surrender in Berlin.[53]

Post-war service[edit source]

Soviet occupation zone[edit source]

Zhukov, Montgomery, Sokolovsky and Rokossovsky at the Brandenburg Gate.

After the German capitulation, Zhukov became the first commander of the Soviet occupation zone. On 10 June 1945, he returned to Moscow to prepare for the Moscow Victory Parade of 1945. On 24 June, Stalin appointed him commander in chief of the parade. After the ceremony, on the night of 24 June, Zhukov went to Berlin to resume his command.[54]

In May 1945, Zhukov signed three resolutions to improve living standards in the Soviet occupation zone:

- 11 May: resolution 063 – provision of food

- 12 May: resolution 064 – restoration of the public services sector

- 13 May: resolution 080 – provision of milk supplies for children

Zhukov requested the Soviet government to transport urgently to Berlin 96,000 tons of grain, 60,000 tons of potatoes, 50,000 cattle, and thousands of tons of other foodstuffs, such as sugar and animal fat. He issued strict orders that his subordinates were to “hate Nazism but respect the German people,”[55] and to make all possible efforts to restore and maintain a stable living standard for the German population.[56]

Inter-allied diplomacy[edit source]

Zhukov sharing a toast with Eisenhower, Montgomery and other Allied officials, June 1945

From 16 July to 2 August, Zhukov participated in the Potsdam Conference with the fellow representatives of the Allied governments. As one of the four commanders of the Allied occupational forces, Zhukov established good relationships with his new colleagues, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, and Marshal Jean de Lattre, and the four frequently exchanged views about such matters as the sentencing, trials, and judgments of war criminals, geopolitical relationships between the Allied states, and how to defeat the Japanese and rebuild Germany.

Eisenhower developed a good relationship with Zhukov and it proved beneficial in resolving differences in post-war occupational issues.[57] Eisenhower’s successor, General Lucius D. Clay, also praised the Zhukov–Eisenhower friendship, and commented: “The Soviet–America relationship should have developed well if Eisenhower and Zhukov had continued to work together.”[58] Zhukov and Eisenhower went on to tour the Soviet Union together in the immediate aftermath of the victory over Germany.[59] During this tour Eisenhower introduced Zhukov to Coca-Cola. As Coca-Cola was regarded in the Soviet Union as a symbol of American imperialism,[60] Zhukov was apparently reluctant to be photographed or reported as consuming such a product. Zhukov asked if the beverage could be made colourless to resemble vodka. A European subsidiary of the Coca-Cola Export Corporation delivered an initial 50 cases of White Coke to Marshal Zhukov.

Decline of career[edit source]

Zhukov at a post-war victory parade in Sverdlovsk, between 1948–1950

Zhukov was not only the supreme military commander of the Soviet occupation zone, but became its military governor on 10 June 1945. He was replaced with Vasily Sokolovsky on 10 April 1946. After an unpleasant session of the main military council — in which Zhukov was accused of egoism, disrespect to his peers and of political unreliability and hostility to the Party Central Committee — he was stripped of his position as commander in chief of the Soviet Army.[2][61][62]

He was assigned command of the Odessa Military District, far from Moscow and lacking in strategic significance and troops. He arrived there on 13 June 1946. Zhukov suffered a heart attack in January 1948, spending a month in the hospital. In February 1948, he was given another secondary posting, this time command of the Urals Military District. Peter G. Tsouras described the move from Odessa to the Urals as a relegation from a “second-rate” to a “fifth-rate” assignment.[63]

Throughout this time, security chief Lavrentiy Beria was supposedly trying to topple Zhukov. Two of Zhukov’s subordinates, Marshal of Aviation Alexander Novikov and Lieutenant-General Konstantin Telegin, were arrested and tortured in Lefortovo Prison at the end of 1945. After Stalin’s death it was claimed that Novikov was allegedly forced by Beria into a “confession” which implicated Zhukov in a conspiracy.[64] In reality, Novikov may have been encouraged to point the finger at Zhukov because he saw Zhukov’s membership at the investigation commission of the Aviators Affair – a purge of the Soviet aircraft industry following accusations that, during the war, the fighter planes had been of poor quality – which Novikov was implicated in, as instrumental to his downfall.[2] Regardless, in a conference, all generals except GRU director Filipp Golikov defended Zhukov against accusation of misspending these accusations. During this time, Zhukov was accused of unauthorized looting of goods confiscated by the Germans and Bonapartism.[61][65]

In 1946, seven rail carriages with furniture that Zhukov was taking to the Soviet Union from Germany were impounded. In 1948, his apartments and house in Moscow were searched and many valuables looted from Germany were found.[66] In his investigation Beria concluded that Zhukov had in his possession 17 golden rings, three gemstones, the faces of 15 golden necklaces, more than four kilometers (2.5 mi) of cloth, 323 pieces of fur, 44 carpets taken from German palaces, 55 paintings and 20 guns.”[67][incomplete short citation] Zhukov admitted in a memorandum to Zhdanov:

“I felt very guilty. I shouldn’t have collected those useless junks and put them into some warehouse, assuming nobody needs them any more. I swear as a Bolshevik that I would avoid such errors and follies thereafter. Surely I still and will wholeheartedly serve the Motherland, the Party, and the Great Comrade Stalin.”[68]

When learning of Zhukov’s “misfortunes”—and despite not understanding all the problems—Eisenhower expressed his sympathy for his “comrade-in-arms.”[69] In February 1953, Stalin relieved Zhukov of his post as Commander of the Urals Military District, recalling Zhukov to Moscow. It was thought Zhukov’s expertise was needed in the Korean War; however, in practice, Zhukov received no orders from Stalin after arriving in Moscow. On 5 March 1953, at 09:50, Stalin died of a stroke. Following Stalin’s passing, Zhukov’s life entered a new phase.[58]

Relationship with Stalin[edit source]

Zhukov with Stalin and Semyon Budyonny during the Soviet Victory Parade of 1945

During the war, Zhukov was one of only a few people who understood Stalin’s personality. As the chief of staff and deputy supreme commander, Zhukov had hundreds of meetings with Stalin, both private and during Stavka conferences. Consequently, Zhukov understood Stalin’s personality and methods well. According to Zhukov, Stalin was a bold and secretive person, but he was also hot-tempered and skeptical. Zhukov was able to gauge Stalin’s mood: for example, when Stalin drew deeply on his tobacco pipe, it was a sign of a good mood. Conversely, if Stalin failed to light his pipe once it was out of tobacco, it was a sign of imminent rage.[70] His outstanding knowledge of Stalin’s personality was an asset that allowed him to deal with Stalin’s outbursts in a way other Soviet generals could not.[71]

Both Zhukov and Stalin were hot-tempered, and both made concessions necessary to sustain their relationship. While Zhukov viewed his relationship with Stalin as one of a subordinate–senior, Stalin was in awe and possibly jealous of Zhukov. Both were military commanders, but Stalin’s experience was limited to a previous generation of non-mechanized warfare. By contrast, Zhukov was highly influential in the development of contemporary combined operations of highly mechanized armies. The differences in their outlooks were the cause of many tempestuous disagreements between the two of them at Stavka meetings. Nonetheless, Zhukov was less competent than Stalin as a politician, highlighted by Zhukov’s many failures in politics. Stalin’s unwillingness to value Zhukov beyond the marshal’s military talents was one of the reasons why Zhukov was recalled from Berlin.[72]

Significant to their relationship as well was Zhukov’s bluntness towards his superior. Stalin was dismissive of the fawning of many of his entourage and openly criticized it.[73] Many people around Stalin—including Beria, Yezhov, and Mekhlis—felt obliged to flatter Stalin to remain on his good side.[74] Zhukov remained obstinate and argumentative, and did not hesitate to publicly contradict Stalin to the point of risking his career and life. Their heated argument about whether to abandon Kiev due to the Germans’ rapid advance in summer of 1941 was typical of Zhukov’s approach.[75] Zhukov’s ability to remain skeptical and unwavering at giving into pressure did garner him the respect of Stalin.

After Stalin[edit source]

Arresting Beria[edit source]

After Stalin’s death, Zhukov returned to favour, becoming Deputy Defence Minister in 1953. He then had an opportunity to avenge himself on Beria. With Stalin’s sudden death, the Soviet Union fell into a leadership crisis. Georgy Malenkov temporarily became First Secretary. Malenkov and his allies attempted to purge Stalin’s influence and personality cult; however, Malenkov himself did not have the courage to do this alone. Moreover, Lavrentiy Beria remained dangerous. The politicians sought reinforcement from the powerful and prestigious military men. In this matter, Nikita Khrushchev chose Zhukov because the two had forged a good relationship, and, in addition, during World War II, Zhukov had twice saved Khrushchev from false accusations.[76][77]

On 26 June 1953, a special meeting of the Soviet Politburo was held by Malenkov. Beria came to the meeting with an uneasy feeling because it was called hastily—indeed, Zhukov had ordered General Kirill Moskalenko to secretly prepare a special force and permitted the force to use two of Zhukov’s and Bulganin’s special cars (which had black glass) in order safely to infiltrate the Kremlin. Zhukov also ordered him to replace the MVD Guard with the guard of the Moscow Military District.

Finally, Khrushchev suggested expelling Beria from the Communist Party and bringing him before a military court. Moskalenko’s special forces obeyed.[78][79]

Zhukov was a member of the military tribunal during the Beria trial, which was headed by Marshal Ivan Konev.[80] On 18 December 1953, the Military Court sentenced Beria to death. During the burial of Beria, Konev commented: “The day this man was born deserves to be damned!” Then Zhukov said: “I considered it as my duty to contribute my little part in this matter.”[78][79]

Minister of Defence[edit source]

When Nikolai Bulganin became premier in 1955, he appointed Zhukov as Defence Minister.[80] Zhukov participated in many political activities. He successfully opposed the re-establishment of the Commissar system, because the Party and political leaders were not professional military, and thus the highest power should fall to the army commanders. Until 1955, Zhukov had both sent and received letters from Eisenhower. Both leaders agreed that the two superpowers should coexist peacefully.[81] In July 1955, Zhukov—together with Khrushchev, Bulganin, Vyacheslav Molotov and Andrei Gromyko—participated in a Summit Conference at Geneva after the USSR signed the Austrian State Treaty and withdrew its army from the country.

Zhukov followed orders from the then Prime Minister Georgy Malenkov and Communist Party leader Khrushchev during the invasion of Hungary following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.[82] Along with the majority of members of the Presidium, he urged Khrushchev to send troops to support the Hungarian authorities and to secure the Austrian border. Zhukov and most of the Presidium were not, however, eager to see a full-scale intervention in Hungary. Zhukov even recommended the withdrawal of Soviet troops when it seemed that they might have to take extreme measures to suppress the revolution.

The mood in the Presidium changed again when Hungary’s new Prime Minister, Imre Nagy, began to talk about Hungarian withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact. That led the Soviets to attack the revolutionaries and to replace Nagy with János Kádár. In the same years, when the UK, France, and Israel invaded Egypt during the Suez crisis, Zhukov expressed support for Egypt’s right of self-defence. In October 1957, Zhukov visited Yugoslavia and Albania aboard the Chapayev-class cruiser Kuibyshev, attempting to repair the Tito–Stalin split of 1948.[83] During the voyage, Kuibyshev encountered units of the U.S. Sixth Fleet and “passing honours” were exchanged between the vessels.

Fall from power[edit source]

On his 60th birthday, in 1956, Zhukov received his fourth Hero of the Soviet Union title – making him the first person to receive the honour four times. The only other four-time recipient was Leonid Brezhnev, who never rose above modest military rank and received all of his four Hero of the Soviet Union medals for his birthday as part of his overall cult of personality and love for medals, titles, and decorations. Despite his general lack of political ability, Zhukov became the highest-ranking military professional who was also a member of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. He further became a symbol of national strength, the most widely-esteemed Soviet military hero of World War II. Zhukov’s prestige was even higher than the police and security agencies of the USSR, and thus rekindled concerns among political leaders.

Going even further than Khrushchev, Zhukov demanded that the political agencies in the Red Army report to him before the Party. He demanded an official condemnation of Stalin’s crimes during the Great Purge.[citation needed] He also supported the political vindication and rehabilitation for Mikhail Tukhachevsky, Grigoriy Shtern, Vasily Blyukher, Alexander Yegorov and many others. In response his opponents accused him of being a Reformist and Bonapartist. Such enviousness and hostility proved to be the key factor that led to his later downfall.[84]

The relationship between Zhukov and Khrushchev reached its peak during the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1956. After becoming the First Secretary of the Party, Khrushchev moved against Stalin’s legacy and criticised his personality cult in a speech, “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences.” To complete such startling acts, Khrushchev needed the approval—or at least the acquiescence—of the military, headed by Minister of Defense Zhukov.

At the plenary session of the Central Committee of the CPSU held in June 1957 Zhukov supported Khrushchev against the “Anti-Party Group“, that had a majority in the Presidium and voted to replace Khrushchev as First Secretary with Bulganin. At that plenum, Zhukov stated: “The Army is against this resolution and not even a tank will leave its position without my order!”[85] In the same session the “Anti-Party Group” was condemned and Zhukov was made a member of the Presidium.

His second fall was more sudden and public even than his first. On 4 October 1957, he left on an official visit to Yugoslavia, and Albania.[86] He returned to Moscow on 26 October, straight to a meeting of the Presidium, during which he was removed from that body. On 2 November, the Central Committee convened to hear Zhukov being accused of ‘non-party behaviour’, conducting an ‘adventurist foreign policy’, and sponsoring his own personality cult. He was expelled from the Central Committee and sent into forced retirement at age 62. The same issue of the Krasnaya Zvezda that announced Zhukov’s return also reported that he had been relieved of his duties.[87] According to many researchers, Soviet politicians—including Khrushchev himself—had a deep-seated fear of “powerful people.”[88][89]

Retirement[edit source]

Zhukov on vacation in Sochi

After being forced out of the government, Zhukov stayed away from politics. Many people—including former subordinates—frequently paid him visits, joined him on hunting excursions, and waxed nostalgic. In September 1959, while visiting the United States, Khrushchev told President Eisenhower that the retired Marshal Zhukov “liked fishing.” Zhukov was actually a keen aquarist.[90] In response, Eisenhower sent Zhukov a set of fishing tackle. Zhukov respected this gift so much that he is said to have exclusively used Eisenhower’s fishing tackle for the remainder of his life.[91]

After Khrushchev was deposed in October 1964, Brezhnev restored Zhukov to favor—though not to power—in a move to use Zhukov’s popularity to strengthen his political position. Zhukov’s name was put in the public eye yet again when Brezhnev lionised Zhukov in a speech commemorating the Great Patriotic War. On 9 May 1965, Zhukov was invited to sit on the tribune of the Lenin Mausoleum and given the honour of reviewing the parade of military forces in Red Square.[92]

Zhukov had begun writing his memoirs, Memories and Recollections, in 1958. He now worked intensively on them, which together with steadily deteriorating health, served to worsen his heart disease. It would take another decade until publication after Zhukov clashed constantly with Mikhail Suslov, the Communist Party’s Chief Ideologue and Second in Command in charge of Censorship, who demanded many revisions and removals, particularly his criticisms of Stalin, Voroshilov, Budyonny and Molotov. After Brezhnev came to power, Suslov made further demands to exaggerate the then-Colonel Brezhnev’s role in WWII by glorifying the little known and strategically unimportant Battles of Malaya Zemlya and Novorossiysk as a decisive turning point in the Eastern Front, both of which Zhukov refused to do.[93] In December 1967, Zhukov had a serious stroke. He was hospitalised until June 1968, and continued to receive medical and rehabilitative treatment at home under the care of his second wife, Galina Semyonova, a former officer in the Medical Corps. The stroke left him paralysed on his left side, his speech became slurred and he could only walk with assistance.

His memoirs were published in 1969 and became a best-seller. Within several months of the date of publication of his memoirs, Zhukov had received more than 10,000 letters from readers that offered comments, expressed gratitude, gave advice, or lavished praise. Supposedly, the Communist Party invited Zhukov to participate in the 24th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1971, but the invitation was rescinded.[94]

Death[edit source]

Zhukov’s grave in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis

On 18 June 1974, Zhukov died after another stroke. Contrary to Zhukov’s last will for an Orthodox Christian burial, and despite the requests of the family to the country’s top leadership,[95] his body was cremated and his ashes were buried at the Kremlin Wall Necropolis alongside fellow generals and marshals of the Soviet Union.

In 1995, an equestrian statue of Zhukov was erected in front of the State Historical Museum.[96] In 1996, on the 100th anniversary of Zhukov’s birth, a panikhida Orthodox memorial service was conducted at his grave, the first such service in the history of the Kremlin Wall Necropolis.[97]

Family[edit source]

FatherKonstantin Artemyevich Zhukov (1851–1921); a shoemakerMotherUstinina Artemievna Zhukova (1866–1944); farmer from a poor familySiblings1. Maria Kostantinovna Zhukova (born 1894)2. Alexei Konstantinovich Zhukov (born 1901); died prematurelySpouse1. Alexandra Dievna Zuikova (1900–1967); common-law wife since 1920; married in 1953; divorced in 1965; died after a stroke2. Galina Alexandrovna Semyonova (1926–1973);[98] married in 1965; medical corps officer, at Burdenko hospital; specialized in therapeutics; died of breast cancerChildren1. Era Zhukova (born 1928); by Alexandra Dievna Zukova2. Margarita Zhukova (1929–2010); by Maria Nikolaevna Volokhova (1897–1983)3. Ella Zhukova (1937–2010); by Alexandra Dievna Zukova4. Maria Zhukova (born 1957); by Galina Alexandrovna Semyonova

Legacy[edit source]

Russian president Dmitry Medvedev and Mongolian president Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj visit the monument to Georgy Zhukov in Ulaanbaatar, near the Zhukov Museum in Zhukov Street (Mongolian: Жуковын гудамж) in memory of the Battle of Khalkin GolStatue of Zhukov on horse in Moscow, with symbols below the horse denoting victory over Germany.

The first monument to Georgy Zhukov was erected in Mongolia, in memory of the Battle of Khalkin Gol. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, this monument was one of the few that did not suffer from anti-Soviet backlash in former Communist states. There is a statue of Zhukov on horseback as he appeared at the 1945 victory parade on Manezhnaya Square at the entrance of the Kremlin in Moscow. Another statue of Zhukov in Moscow is located on Prospekt Marshala Zhukova. A statue of Zhukov is located in the town of Irbit, in the Sverdlovsk Oblast. Other statues of Zhukov are found in Omsk, Irkutsk and Yekaterinburg.

A minor planet, 2132 Zhukov, discovered in 1975, by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Chernykh, is named in his honour.[99] In 1996, Russia adopted the Order of Zhukov and the Zhukov Medal to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birthday.

Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky‘s poem On the Death of Zhukov (“Na smert’ Zhukova”, 1974) is regarded by critics as one of the best poems on the war written by an author of the post-war generation.[100] The poem is a stylization of The Bullfinch, Derzhavin‘s elegy on the death of Generalissimo Suvorov in 1800. Brodsky draws a parallel between the careers of these two famous commanders. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn re-interpreted Zhukov’s memoirs in the short story Times of Crisis.

In his book of recollections,[101] Zhukov was critical of the role the Soviet leadership played during the war. The first edition of Vospominaniya i razmyshleniya was published during Brezhnev’s premiership only on the conditions that criticism of Stalin was removed, and that Zhukov add a (fictional) episode of a visit to Leonid Brezhnev, politruk on the Southern Front, to consult on military strategy.[102]

In 1989, parts of previously unpublished chapters from Zhukov’s memoir were published by Pravda, which his daughter said had been hidden in a safe until they could be published. The excerpts included criticism of the 1937–1939 purges for annihilating “[M]any thousands of outstanding party workers” and stated that Stalin had played no role in directing the war effort, although he often issued orders devised by the general staff as if they were his own.[103]

Appraisals of Zhukov’s career vary. For example, historian Konstantin Zaleski claimed that Zhukov exaggerated his own role in World War II.[104] Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky said that the planning and decisions for the battle of Kursk were made without Zhukov, that he only arrived just before the battle, made no decisions and left soon after.[45]

Zhukov also received many positive comments, mostly from his Army companions, from the modern Russian Army, and from his Allied contemporaries. General of the Army Eisenhower stated that, because of Zhukov’s achievements fighting the Nazis, the United Nations owed him much more than any other military leader in the world. “The war in Europe ended with victory and nobody could have done that better than Marshal Zhukov – we owed him that credit. He is a modest person, and so we can’t undervalue his position in our mind. When we can come back to our Motherland, there must be another type of Order in Russia, an Order named after Zhukov, which is awarded to everybody who can learn the bravery, the far vision, and the decisiveness of this soldier.”[105]

Marshal of the Soviet Union Aleksandr Vasilevsky commented that Zhukov is one of the most outstanding and brilliant military commanders of the Soviet military forces.[106] Major General Sir Francis de Guingand, chief of staff of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, described Zhukov as a friendly person.[107] John Gunther, who met Zhukov many times after the war, said that Zhukov was more friendly and honest than any of the other Soviet leaders.[108]

John Eisenhower—son of Dwight Eisenhower—claimed that Zhukov was really ebullient and was a friend of his.[81] Albert Axell in his work “Marshal Zhukov, the one who beat Hitler” claimed that Zhukov was a military genius like Alexander the Great and Napoleon. Axell also commented that Zhukov was a loyal communist and a patriot.[109] At the end of his work about Zhukov, Otto Chaney concluded: “But Zhukov belongs to all of us. In the darkest period of World War II his fortitude and determination eventually triumphed. For Russians and people everywhere he remains an enduring symbol of victory on the battlefield.”[110]

In Russia, Zhukov is often credited for his “prophetic” words confessed to Konstantin Rokossovsky in Berlin, 1945: “We have liberated them, and they will never forgive us for that”.[111]

In popular culture[edit source]

Zhukov has been portrayed by the following actors:

- Fedor Blasevich in The Vow and The Fall of Berlin

- Mikhail Ulyanov in Stalingrad, Battle of Moscow, and Take Aim

- Vladimir Menshov in The General and Liquidation

- Valeriy Grishko in White Tiger

- Jason Isaacs in The Death of Stalin

Decorations[edit source]

Russian PresidentDmitry Medvedev laying a wreath at a monument to Zhukov in Ulaanbaatar, while on a state visit to Mongolia in August 2009.Marshal Zhukov depicted on façade of Victory Memorial, Prokhorovka, Russia

Zhukov was the recipient of many decorations. Most notably he was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union four times. Aside from Zhukov, only Leonid Brezhnev was a four-time recipient (the latter’s were self-awarded).

Zhukov was one of only three recipients to receive the Order of Victory twice. He was also awarded high honours from many other countries. A partial listing is presented below.

Imperial Russia[edit source]

| Cross of St. George, 3rd class |

| Cross of St. George, 4th class |

Soviet Union[edit source]

Foreign[edit source]

References[edit source]

Citations[edit source]

- ^ “Герои Страны”.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Roberts, Geoffrey (2012). Stalin’s General: The Life of Georgy Zhukov. London, UK: Icon Books. p. 11, 244–245. ISBN 978-1-8483-1443-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Stalin’s General, p. 12.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Stalin’s General, p. 13.

- ^ (in Russian) B. V. Sokolov (2000) В огне революции и гражданской войны, in Неизвестный Жуков: портрет без ретуши в зеркале эпохи, Minsk: Rodiola-plus.

- ^ Zhukov 2002, pp. 79, 90.

- ^ Zhukov 2002, p. 87.

- ^ Zhukov 2002, p. 89.

- ^ Stalin’s General, p. 49.

- ^ Zhukov 2002, p. 99.

- ^ Jump up to:a b M. A. Gareev (1996) Маршал Жуков. Величие и уникальность полководческого искусства. Ufa

- ^ Zhukov 2002, p. 151.

- ^ Zhukov 2002, p. 158.

- ^ Coox 1985, p. 579.

- ^ Coox 1985, p. 590.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Coox 1985, p. 633.

- ^ Coox 1985, pp. 991–998.

- ^ Coox 1985, p. 998.

- ^ Coox 1985, p. 996.

- ^ “Folio 37977. inventory 5, file 564, sheets 32–34”. Central State Archive of the Red Army. TsGAKA.

- ^ Zhukov 2002, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g П. Н. БОБЫЛЕВ “Репетиция катастрофы” // “Военно-исторический журнал” № 7, 8, 1993 г. [1]

- ^ Vasilevsky 1973, p. 24.

- ^ Zhukov 2002, p. 205.

- ^ A. M. Vasilevsky (May 1941) “Соображения по плану стратегического развёртывания сил Советского Союза на случай войны с Германией и её союзниками”. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2012.. tuad.nsk.ru

- ^ Viktor Suvorov (2006). Стратегические замыслы Сталина накануне 22 июня 1941 года, in Правда Виктора Суворова: переписывая историю Второй мировой, Moscow: Yauza

- ^ Mikhail I. Meltyukhov (1999) Упущенный шанс Сталина. Советский Союз и борьба за Европу, 1939–1941. Moscow

- ^ Murphy, David E. (2005). What Stalin Knew: The Enigma of Barbarossa. New Haven: Yale U.P. pp. 135–36. ISBN 0-300-10780-3.

- ^ Uldricks 1999, p. 629.

- ^ Uldricks 1999, pp. 629–630.

- ^ Chant, Christopher (2020). “Operation Barbarossa”. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ Kashuba, Steven (2013). Destination Gulag. Bloomington: Trafford Publishing. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-4669-8312-0.

- ^ Zhukov 2003, p. 269.

- ^ P. Ya. Mezhiritzky (2002), Reading Marshal Zhukov, Philadelphia: Libas Consulting, chapter 32.

- ^ Pleshakov, Constantine (2005). Stalin’s Folly: The Secret History of the German Invasion of Russia, June 1941. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-297-84626-0.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Zhukov 2003, p. 353.

- ^ Zhukov 2003, p. 382.

- ^ Zhukov 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Zhukov 2003, p. 16.

- ^ Chaney 1996, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Chaney 1996, p. 224.

- ^ Махмут А. Гареев Маршал Жуков. Величие и уникальность полководческого искусства. М.: – Уфа, 1996.

- ^ Ziemke, Earl Frederick; Bauer, Magna E. (1987). Moscow to Stalingrad: Decision in the East. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. p. 507. ISBN 978-0-1608-0081-8 – via Google Books.

- ^ Roberts, Geoffrey (2006). Stalin’s Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939-1953. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 159. ISBN 0-300-11204-1.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Военно-исторический журнал, 1992 N3 p. 31.

- ^ Kokoshin, Andreĭ Afanas’evich (1998). Soviet Strategic Thought, 1917–1991. MIT Press. p. 43.

- ^ Zhukov 2003, p. 205.

- ^ Zhukov 2003, pp. 209–217.

- ^ Zhukov 2003, p. 222.

- ^ Zhukov 2003, p. 246.

- ^ Zhukov 2003, p. 259.

- ^ William I. Hitchcock, The Bitter Road to Freedom: A New History of the Liberation of Europe (2008) pp. 160–161.

- ^ Zhukov 2003, p. 332.

- ^ Shtemenko 1989, pp. 566–569.

- ^ Tibbetts, Jann (30 July 2016). 50 Great Military Leaders of All Time. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-85505-66-9.

- ^ Grigori Deborin (1958). Вторая мировая война. Военно-политический очерк, Moscow: Voenizdat, pp. 340–343.

- ^ Clark, Douglas E. (2013). Eisenhower in Command at Columbia. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7391-7836-2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Axell 2003, p. 356.

- ^ Chaney 1996, pp. 346–347.

- ^ Mark Pendergrast (15 August 1993). “Viewpoints; A Brief History of Coca-Colonization”. The New York Times. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Boterbloem, Kees (1 March 2004). Life and Times of Andrei Zhdanov, 1896-1948. McGill-Queen’s Press – MQUP. p. 477. ISBN 978-0-7735-7173-0.

- ^ Spahr 1993, pp. 200–205.

- ^ Tsouras, P.G. (1994). Changing Orders: The evolution of the World’s Armies, 1945 to the Present. Facts on File, Inc. pp. 43–44. ISBN 0-8160-3122-3.

- ^ Kornukov, A. M. [2] (Chief Marshal of Aviation AA. Novikov – His 100th Birthday) Warheroes.ru. Retrieved on 8 July 2019.

- ^ I. S. Konev (1991) Записки командующего фронтом (Diary of the Front Commander). Voenizdat. Moscow. pp. 594–599. Warheroes.ru. Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- ^ Boris Vadimovich Sokolov (2000) Неизвестный Жуков: портрет без ретуши в зеркале эпохи. (Unknown Zhukov), Minsk, Rodiola-plyus, ISBN 985-448-036-4.

- ^ Жуков Георгий Константинович. БИОГРАФИЧЕСКИЙ УКАЗАТЕЛЬ. Hrono.ru. Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- ^ Военные архивы России. – М., 1993, p. 244.

- ^ The New York Times. 29 July 1955.

- ^ G. K. Zhukov. Reminiscences and Reflections. vol. 2, pp. 139, 150.

- ^ Axell 2003, p. 280.

- ^ Chaney 1996.

- ^ Shtemenko 1989, p. 587.

- ^ Vasilevsky 1973, p. 62.

- ^ A. I. Sethi. Marshal Zhukov: The Great Strategician. New Delhi: 1988, p. 187.

- ^ Vasilevsky 1973, p. 137.

- ^ Sergei Khrushchev (1990). Khrushchev on Khrushchev. An Inside Account of the Man and His Era, Little, Brown & Company, Boston, pp. 243, 272, 317. ISBN 0316491942.

- ^ Jump up to:a b K. S. Moskalenko (1990). The arrest of Beria. Newspaper Московские новости. No. 23.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Afanasyev 1989, p. 141.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Associated Press, 9 February 1955, reported in The Albuquerque Journal p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to:a b John Eisenhower (1974). Strictly Personal. New York. 1974. p. 237, ISBN 0385070713.

- ^ Johanna Granville (2004) The First Domino: International Decision Making During the Hungarian Crisis of 1956, Texas A & M University Press, ISBN 1-58544-298-4

- ^ Spahr 1993, pp. 235–238.

- ^ Spahr 1993, p. 391.

- ^ Afanasyev 1989, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Chaney 1996, pp. 444–445.

- ^ Spahr 1993, p. 238.

- ^ Afanasyev 1989, p. 152.

- ^ Chaney 1996, pp. 453–455.

- ^ Nowak, Eugeniusz (1998). “Erinnerungen an Ornithologen, die ich kannte”. J. Ornithol. (in German). 139 (3): 325–348. doi:10.1007/BF01653343. S2CID 28973619.

- ^ Korda, M. (2008) Ike: An American Hero

- ^ Axell 2003, p. 277.

- ^ Thelman, Joseph (December 2012). “The Man in Galoshes”. Jew Observer. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ Spahr 1993, p. 411.

- ^ “Маршал Жуков – Воспоминания дочери (Марии)“.

- ^ Williams, C. J. (2 May 1995). “At Last, a Soviet Hero Gets Respect: Marshal Georgi Zhukov was demoted twice after leading victorious World War II forces. Now he is being honored with a medal, a monument and a museum”. LA Times. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ Станислав МИНАКОВ. Жуков как сын церкви (Еженедельник 2000 выпуск № 51 (347) 22–28 декабря 2006 г.) Archived 29 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tony Le Tissier (1996). Zhukov at the Oder: The Decisive Battle for Berlin. London, p. 258, ISBN 0811736091.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 173. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

- ^ Shlapentokh, Dmitry. The Russian boys and their last poet. The National Interest. 22 June 1996 Retrieved on 17 July 2002

- ^ G. K. Zhukov (2002) Воспоминания и размышления. Olma-Press.

- ^ Mauno Koivisto Venäjän idea, Helsinki. Tammi. 2001.

- ^ “Soviets Print Excerpts of Attack by Zhukov on Stalin’s War Role”. The New York Times. 21 January 1989. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Залесский К. А. Империя Сталина. Биографический энциклопедический словарь. Москва, Вече, 2000; Жуков Георгий Константинович. Хронос, биографии (in Russian)

- ^ Dwight D. Eisenhower (1948) Crusade in Europe, New York.

- ^ Vasilevsky 1973, p. 568.

- ^ Sir Francis de Guingand. Generals at War. London. 1972

- ^ John Gunther. Inside Russia Today. New York. 1958.

- ^ The general who defeated Hitler. 8 May 2005. BBC Vietnamese (in Vietnamese)

- ^ Chaney 1996, p. 483.

- ^ “«Мы их освободили, и они нам этого никогда не простят», — пророческая фраза маршала Победы Георгия Жукова” [“We have liberated them, and they will never forgive us for that,” – the prophetic phrase of Victory Marshal Georgy Zhukov]. gazeta-delovoy-mir.ru (in Russian). 10 June 2021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

Bibliography[edit source]

- Afanasyev, Y. N., ed. (1989). There Is No Other Way (in Russian). Moscow: Progress Publishers. OCLC 495955198.

- Axell, A. (2003). Marshal Zhukov: The Man Who Beat Hitler. London: Pearson Longman. ISBN 9780582772335.

- Chaney, O. P. (1996). Zhukov (revised ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806128078.

- Coox, A. D. (1985). Nomonhan: Japan Against Russia, 1939. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804711609.

- Isaev, A. V. (2006). Zhukov: The Last Argument of the King (in Russian). Moscow: Yauza Publishing. ISBN 9785699165643.

- Roberts, Geoffrey (2012). Stalin’s General: The Life of Georgy Zhukov. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780679645177.

- Shtemenko, S. M. (1989). General Staff during the War (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. ISBN 9785203004918.

- Spahr, W. J. (1993). Zhukov: The Rise and Fall of a Great Captain. Novato: Presidio Press. ISBN 9780891414698.

- Uldricks, T. J. (1999). “The Icebreaker Controversy”. Slavic Review. 58 (3): 626–643. doi:10.2307/2697571. JSTOR 2697571.

- Vasilevsky, A. M. (1973). A Lifelong Cause (in Russian). Moscow: Progress Publishers. OCLC 988160134.

- Zhukov, G. К. (1973). The Memoirs of Marshal Zhukov. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 9780224619240.

- Zhukov, G. K. (2002). Memories and Reflections (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow: Olma Press. ISBN 9785224031955.

- Zhukov, G. K. (2003). Memories and Reflections (in Russian). Vol. 2. Moscow: Olma Press. ISBN 9785224031979.

- Zhukov, Georgi (1969). Marshal Zhukov’s Greatest Battles. New York: Harper & Row. (in English, edited & commentary by Harrison E. Salisbury)

Further reading[edit source]

- Goldman, S. D. (2013). Nomonhan, 1939: the Red Army’s victory that shaped World War II. Annapolis: NIP. ISBN 9781591143390.

- Hill, A. (2017). The Red Army and the Second World War. Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 9781107020795.

External links[edit source]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Georgy Zhukov |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Georgy Zhukov. |

- Reminiscences and Reflections, two-volume English-language translation of Zhukov’s memoirs by Progress Publishers, 1985: Volume 1, Volume 2

- Georgy Zhukov Newsreels at Net-Film Newsreels and Documentary Films Archive

- Works by Georgy Zhukov at Open Library

- Works by or about Georgy Zhukov at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Georgy Zhukov in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Georgy Zhukov – WWII Marshal of the Soviet Union

- Newspaper clippings about Georgy Zhukov in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW