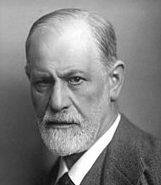

Sigmund Freud (/frɔɪd/ FROYD,[3] German: [ˈziːkmʊnt ˈfʁɔʏ̯t]; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies in the psyche through dialogue between a patient and a psychoanalyst.[4]

Freud was born to Galician Jewish parents in the Moravian town of Freiberg, in the Austrian Empire. He qualified as a doctor of medicine in 1881 at the University of Vienna.[5][6] Upon completing his habilitation in 1885, he was appointed a docent in neuropathology and became an affiliated professor in 1902.[7] Freud lived and worked in Vienna, having set up his clinical practice there in 1886. In 1938, Freud left Austria to escape Nazi persecution. He died in exile in the United Kingdom in 1939.

In founding psychoanalysis, Freud developed therapeutic techniques such as the use of free association and discovered transference, establishing its central role in the analytic process. Freud’s redefinition of sexuality to include its infantile forms led him to formulate the Oedipus complex as the central tenet of psychoanalytical theory.[8] His analysis of dreams as wish-fulfillments provided him with models for the clinical analysis of symptom formation and the underlying mechanisms of repression. On this basis, Freud elaborated his theory of the unconscious and went on to develop a model of psychic structure comprising id, ego and super-ego.[9] Freud postulated the existence of libido, sexualised energy with which mental processes and structures are invested and which generates erotic attachments, and a death drive, the source of compulsive repetition, hate, aggression, and neurotic guilt.[10] In his later works, Freud developed a wide-ranging interpretation and critique of religion and culture.

Though in overall decline as a diagnostic and clinical practice, psychoanalysis remains influential within psychology, psychiatry, and psychotherapy, and across the humanities. It thus continues to generate extensive and highly contested debate concerning its therapeutic efficacy, its scientific status, and whether it advances or hinders the feminist cause.[11] Nonetheless, Freud’s work has suffused contemporary Western thought and popular culture. W. H. Auden‘s 1940 poetic tribute to Freud describes him as having created “a whole climate of opinion / under whom we conduct our different lives”.[12]

Contents

- 1Biography

- 2Ideas

- 3Legacy

- 4In popular culture

- 5Works

- 6Correspondence

- 7See also

- 8Notes

- 9References

- 10Further reading

- 11External links

Biography[edit source]

Early life and education[edit source]

Freud’s birthplace, a rented room in a locksmith’s house, Freiberg, Austrian Empire (later Příbor, Czech Republic)Freud (aged 16) and his mother, Amalia, in 1872

Sigmund Freud was born to Ashkenazi Jewish parents in the Moravian town of Freiberg,[13][14] in the Austrian Empire (now Příbor, Czech Republic), the first of eight children.[15] Both of his parents were from Galicia, a historic province straddling modern-day West Ukraine and southeast Poland. His father, Jakob Freud (1815–1896), a wool merchant, had two sons, Emanuel (1833–1914) and Philipp (1836–1911), by his first marriage. Jakob’s family were Hasidic Jews and, although Jakob himself had moved away from the tradition, he came to be known for his Torah study. He and Freud’s mother, Amalia Nathansohn, who was 20 years younger and his third wife, were married by Rabbi Isaac Noah Mannheimer on 29 July 1855.[16] They were struggling financially and living in a rented room, in a locksmith’s house at Schlossergasse 117 when their son Sigmund was born.[17] He was born with a caul, which his mother saw as a positive omen for the boy’s future.[18]

In 1859, the Freud family left Freiberg. Freud’s half-brothers immigrated to Manchester, England, parting him from the “inseparable” playmate of his early childhood, Emanuel’s son, John.[19] Jakob Freud took his wife and two children (Freud’s sister, Anna, was born in 1858; a brother, Julius born in 1857, had died in infancy) firstly to Leipzig and then in 1860 to Vienna where four sisters and a brother were born: Rosa (b. 1860), Marie (b. 1861), Adolfine (b. 1862), Paula (b. 1864), Alexander (b. 1866). In 1865, the nine-year-old Freud entered the Leopoldstädter Kommunal-Realgymnasium, a prominent high school. He proved to be an outstanding pupil and graduated from the Matura in 1873 with honors. He loved literature and was proficient in German, French, Italian, Spanish, English, Hebrew, Latin and Greek.[20]

Freud entered the University of Vienna at age 17. He had planned to study law, but joined the medical faculty at the university, where his studies included philosophy under Franz Brentano, physiology under Ernst Brücke, and zoology under Darwinist professor Carl Claus.[21] In 1876, Freud spent four weeks at Claus’s zoological research station in Trieste, dissecting hundreds of eels in an inconclusive search for their male reproductive organs.[22] In 1877, Freud moved to Ernst Brücke’s physiology laboratory where he spent six years comparing the brains of humans and other vertebrates with those of frogs and invertebrates such as crayfish and lampreys. His research work on the biology of nervous tissue proved seminal for the subsequent discovery of the neuron in the 1890s.[23] Freud’s research work was interrupted in 1879 by the obligation to undertake a year’s compulsory military service. The lengthy downtimes enabled him to complete a commission to translate four essays from John Stuart Mill‘s collected works.[24] He graduated with an MD in March 1881.[25]

Early career and marriage[edit source]

In 1882, Freud began his medical career at Vienna General Hospital. His research work in cerebral anatomy led to the publication in 1884 of an influential paper on the palliative effects of cocaine, and his work on aphasia would form the basis of his first book On Aphasia: A Critical Study, published in 1891.[26] Over a three-year period, Freud worked in various departments of the hospital. His time spent in Theodor Meynert‘s psychiatric clinic and as a locum in a local asylum led to an increased interest in clinical work. His substantial body of published research led to his appointment as a university lecturer or docent in neuropathology in 1885, a non-salaried post but one which entitled him to give lectures at the University of Vienna.[27]

In 1886, Freud resigned his hospital post and entered private practice specializing in “nervous disorders”. The same year he married Martha Bernays, the granddaughter of Isaac Bernays, a chief rabbi in Hamburg. They had six children: Mathilde (b. 1887), Jean-Martin (b. 1889), Oliver (b. 1891), Ernst (b. 1892), Sophie (b. 1893), and Anna (b. 1895). From 1891 until they left Vienna in 1938, Freud and his family lived in an apartment at Berggasse 19, near Innere Stadt, a historical district of Vienna.Freud’s home at Berggasse 19, Vienna

In 1896, Minna Bernays, Martha Freud’s sister, became a permanent member of the Freud household after the death of her fiancé. The close relationship she formed with Freud led to rumours, started by Carl Jung, of an affair. The discovery of a Swiss hotel guest-book entry for 13 August 1898, signed by Freud whilst travelling with his sister-in-law, has been presented as evidence of the affair.[28]

Freud began smoking tobacco at age 24; initially a cigarette smoker, he became a cigar smoker. He believed smoking enhanced his capacity to work and that he could exercise self-control in moderating it. Despite health warnings from colleague Wilhelm Fliess, he remained a smoker, eventually suffering a buccal cancer.[29] Freud suggested to Fliess in 1897 that addictions, including that to tobacco, were substitutes for masturbation, “the one great habit.”[30]

Freud had greatly admired his philosophy tutor, Brentano, who was known for his theories of perception and introspection. Brentano discussed the possible existence of the unconscious mind in his Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint (1874). Although Brentano denied its existence, his discussion of the unconscious probably helped introduce Freud to the concept.[31] Freud owned and made use of Charles Darwin‘s major evolutionary writings, and was also influenced by Eduard von Hartmann‘s The Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869). Other texts of importance to Freud were by Fechner and Herbart,[32] with the latter’s Psychology as Science arguably considered to be of underrated significance in this respect.[33] Freud also drew on the work of Theodor Lipps, who was one of the main contemporary theorists of the concepts of the unconscious and empathy.[34]

Though Freud was reluctant to associate his psychoanalytic insights with prior philosophical theories, attention has been drawn to analogies between his work and that of both Schopenhauer[35] and Nietzsche. In 1908, Freud said that he occasionally read Nietzsche, and had a strong fascination for his writings, but did not study him, because he found Nietzsche’s “intuitive insights” resembled too much his own work at the time, and also because he was overwhelmed by the “wealth of ideas” he encountered when he read Nietzsche. Freud sometimes would deny the influence of Nietzsche’s ideas. One historian quotes Peter L. Rudnytsky, who says that based on Freud’s correspondence with his adolescent friend Eduard Silberstein, Freud read Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy and probably the first two of the Untimely Meditations when he was seventeen.[36][37] In 1900, the year of Nietzsche’s death, Freud bought his collected works; he told his friend, Fliess, that he hoped to find in Nietzsche’s works “the words for much that remains mute in me.” Later, he said he had not yet opened them.[38] Freud came to treat Nietzsche’s writings “as texts to be resisted far more than to be studied.” His interest in philosophy declined after he had decided on a career in neurology.[39]

Freud read William Shakespeare in English throughout his life, and it has been suggested that his understanding of human psychology may have been partially derived from Shakespeare’s plays.[40]

Freud’s Jewish origins and his allegiance to his secular Jewish identity were of significant influence in the formation of his intellectual and moral outlook, especially concerning his intellectual non-conformism, as he was the first to point out in his Autobiographical Study.[41] They would also have a substantial effect on the content of psychoanalytic ideas, particularly in respect of their common concerns with depth interpretation and “the bounding of desire by law”.[42]

Development of psychoanalysis[edit source]

André Brouillet‘s A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière (1887) depicting a Charcot demonstration. Freud had a lithograph of this painting placed over the couch in his consulting rooms.[43]

In October 1885, Freud went to Paris on a three-month fellowship to study with Jean-Martin Charcot, a renowned neurologist who was conducting scientific research into hypnosis. He was later to recall the experience of this stay as catalytic in turning him toward the practice of medical psychopathology and away from a less financially promising career in neurology research.[44] Charcot specialized in the study of hysteria and susceptibility to hypnosis, which he frequently demonstrated with patients on stage in front of an audience.

Once he had set up in private practice back in Vienna in 1886, Freud began using hypnosis in his clinical work. He adopted the approach of his friend and collaborator, Josef Breuer, in a type of hypnosis that was different from the French methods he had studied, in that it did not use suggestion. The treatment of one particular patient of Breuer’s proved to be transformative for Freud’s clinical practice. Described as Anna O., she was invited to talk about her symptoms while under hypnosis (she would coin the phrase “talking cure” for her treatment). In the course of talking in this way, her symptoms became reduced in severity as she retrieved memories of traumatic incidents associated with their onset.

The inconsistent results of Freud’s early clinical work eventually led him to abandon hypnosis, having concluded that more consistent and effective symptom relief could be achieved by encouraging patients to talk freely, without censorship or inhibition, about whatever ideas or memories occurred to them. In conjunction with this procedure, which he called “free association“, Freud found that patients’ dreams could be fruitfully analyzed to reveal the complex structuring of unconscious material and to demonstrate the psychic action of repression which, he had concluded, underlay symptom formation. By 1896 he was using the term “psychoanalysis” to refer to his new clinical method and the theories on which it was based.[45]Approach to Freud’s consulting rooms at Berggasse 19

Freud’s development of these new theories took place during a period in which he experienced heart irregularities, disturbing dreams and periods of depression, a “neurasthenia” which he linked to the death of his father in 1896[46] and which prompted a “self-analysis” of his own dreams and memories of childhood. His explorations of his feelings of hostility to his father and rivalrous jealousy over his mother’s affections led him to fundamentally revise his theory of the origin of the neuroses.

Based on his early clinical work, Freud had postulated that unconscious memories of sexual molestation in early childhood were a necessary precondition for the psychoneuroses (hysteria and obsessional neurosis), a formulation now known as Freud’s seduction theory.[47] In the light of his self-analysis, Freud abandoned the theory that every neurosis can be traced back to the effects of infantile sexual abuse, now arguing that infantile sexual scenarios still had a causative function, but it did not matter whether they were real or imagined and that in either case, they became pathogenic only when acting as repressed memories.[48]

This transition from the theory of infantile sexual trauma as a general explanation of how all neuroses originate to one that presupposes autonomous infantile sexuality provided the basis for Freud’s subsequent formulation of the theory of the Oedipus complex.[49]

Freud described the evolution of his clinical method and set out his theory of the psychogenetic origins of hysteria, demonstrated in several case histories, in Studies on Hysteria published in 1895 (co-authored with Josef Breuer). In 1899, he published The Interpretation of Dreams in which, following a critical review of existing theory, Freud gives detailed interpretations of his own and his patients’ dreams in terms of wish-fulfillments made subject to the repression and censorship of the “dream-work”. He then sets out the theoretical model of mental structure (the unconscious, pre-conscious and conscious) on which this account is based. An abridged version, On Dreams, was published in 1901. In works that would win him a more general readership, Freud applied his theories outside the clinical setting in The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901) and Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (1905).[50] In Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, published in 1905, Freud elaborates his theory of infantile sexuality, describing its “polymorphous perverse” forms and the functioning of the “drives”, to which it gives rise, in the formation of sexual identity.[51] The same year he published Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria, which became one of his more famous and controversial case studies.[52]

Relationship with Fliess[edit source]

During this formative period of his work, Freud valued and came to rely on the intellectual and emotional support of his friend Wilhelm Fliess, a Berlin-based ear, nose, and throat specialist whom he had first met in 1887. Both men saw themselves as isolated from the prevailing clinical and theoretical mainstream because of their ambitions to develop radical new theories of sexuality. Fliess developed highly eccentric theories of human biorhythms and a nasogenital connection which are today considered pseudoscientific. He shared Freud’s views on the importance of certain aspects of sexuality – masturbation, coitus interruptus, and the use of condoms – in the etiology of what was then called the “actual neuroses,” primarily neurasthenia and certain physically manifested anxiety symptoms.[53] They maintained an extensive correspondence from which Freud drew on Fliess’s speculations on infantile sexuality and bisexuality to elaborate and revise his own ideas. His first attempt at a systematic theory of the mind, his Project for a Scientific Psychology was developed as a metapsychology with Fliess as interlocutor.[54] However, Freud’s efforts to build a bridge between neurology and psychology were eventually abandoned after they had reached an impasse, as his letters to Fliess reveal,[55] though some ideas of the Project were to be taken up again in the concluding chapter of The Interpretation of Dreams.[56]

Freud had Fliess repeatedly operate on his nose and sinuses to treat “nasal reflex neurosis”,[57] and subsequently referred his patient Emma Eckstein to him. According to Freud, her history of symptoms included severe leg pains with consequent restricted mobility, as well as stomach and menstrual pains. These pains were, according to Fliess’s theories, caused by habitual masturbation which, as the tissue of the nose and genitalia were linked, was curable by removal of part of the middle turbinate.[58][59] Fliess’s surgery proved disastrous, resulting in profuse, recurrent nasal bleeding; he had left a half-metre of gauze in Eckstein’s nasal cavity whose subsequent removal left her permanently disfigured. At first, though aware of Fliess’s culpability and regarding the remedial surgery in horror, Freud could bring himself only to intimate delicately in his correspondence with Fliess the nature of his disastrous role, and in subsequent letters maintained a tactful silence on the matter or else returned to the face-saving topic of Eckstein’s hysteria. Freud ultimately, in light of Eckstein’s history of adolescent self-cutting and irregular nasal (and menstrual) bleeding, concluded that Fliess was “completely without blame”, as Eckstein’s post-operative haemorrhages were hysterical “wish-bleedings” linked to “an old wish to be loved in her illness” and triggered as a means of “rearousing [Freud’s] affection”. Eckstein nonetheless continued her analysis with Freud. She was restored to full mobility and went on to practice psychoanalysis herself.[60][61][58]

Freud, who had called Fliess “the Kepler of biology”, later concluded that a combination of a homoerotic attachment and the residue of his “specifically Jewish mysticism” lay behind his loyalty to his Jewish friend and his consequent over-estimation of both his theoretical and clinical work. Their friendship came to an acrimonious end with Fliess angry at Freud’s unwillingness to endorse his general theory of sexual periodicity and accusing him of collusion in the plagiarism of his work. After Fliess failed to respond to Freud’s offer of collaboration over the publication of his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality in 1906, their relationship came to an end.[62]

Early followers[edit source]

Group photo 1909 in front of Clark University. Front row: Sigmund Freud, G. Stanley Hall, Carl Jung; back row: Abraham Brill, Ernest Jones, Sándor Ferenczi

In 1902, Freud, at last, realised his long-standing ambition to be made a university professor. The title “professor extraordinarius”[63] was important to Freud for the recognition and prestige it conferred, there being no salary or teaching duties attached to the post (he would be granted the enhanced status of “professor ordinarius” in 1920).[64] Despite support from the university, his appointment had been blocked in successive years by the political authorities and it was secured only with the intervention of one of his more influential ex-patients, a Baroness Marie Ferstel, who (supposedly) had to bribe the minister of education with a valuable painting.[65]

With his prestige thus enhanced, Freud continued with the regular series of lectures on his work which, since the mid-1880s as a docent of Vienna University, he had been delivering to small audiences every Saturday evening at the lecture hall of the university’s psychiatric clinic.[66]

From the autumn of 1902, a number of Viennese physicians who had expressed interest in Freud’s work were invited to meet at his apartment every Wednesday afternoon to discuss issues relating to psychology and neuropathology.[67] This group was called the Wednesday Psychological Society (Psychologische Mittwochs-Gesellschaft) and it marked the beginnings of the worldwide psychoanalytic movement.[68]

Freud founded this discussion group at the suggestion of the physician Wilhelm Stekel. Stekel had studied medicine at the University of Vienna under Richard von Krafft-Ebing. His conversion to psychoanalysis is variously attributed to his successful treatment by Freud for a sexual problem or as a result of his reading The Interpretation of Dreams, to which he subsequently gave a positive review in the Viennese daily newspaper Neues Wiener Tagblatt.[69]

The other three original members whom Freud invited to attend, Alfred Adler, Max Kahane, and Rudolf Reitler, were also physicians[70] and all five were Jewish by birth.[71] Both Kahane and Reitler were childhood friends of Freud. Kahane had attended the same secondary school and both he and Reitler went to university with Freud. They had kept abreast of Freud’s developing ideas through their attendance at his Saturday evening lectures.[72] In 1901, Kahane, who first introduced Stekel to Freud’s work,[66] had opened an out-patient psychotherapy institute of which he was the director in Bauernmarkt, in Vienna.[67] In the same year, his medical textbook, Outline of Internal Medicine for Students and Practicing Physicians, was published. In it, he provided an outline of Freud’s psychoanalytic method.[66] Kahane broke with Freud and left the Wednesday Psychological Society in 1907 for unknown reasons and in 1923 committed suicide.[73] Reitler was the director of an establishment providing thermal cures in Dorotheergasse which had been founded in 1901.[67] He died prematurely in 1917. Adler, regarded as the most formidable intellect among the early Freud circle, was a socialist who in 1898 had written a health manual for the tailoring trade. He was particularly interested in the potential social impact of psychiatry.[74]

Max Graf, a Viennese musicologist and father of “Little Hans“, who had first encountered Freud in 1900 and joined the Wednesday group soon after its initial inception,[75] described the ritual and atmosphere of the early meetings of the society:

The gatherings followed a definite ritual. First one of the members would present a paper. Then, black coffee and cakes were served; cigars and cigarettes were on the table and were consumed in great quantities. After a social quarter of an hour, the discussion would begin. The last and decisive word was always spoken by Freud himself. There was the atmosphere of the foundation of a religion in that room. Freud himself was its new prophet who made the heretofore prevailing methods of psychological investigation appear superficial.[74]

Carl Jung in 1910

By 1906, the group had grown to sixteen members, including Otto Rank, who was employed as the group’s paid secretary.[74] In the same year, Freud began a correspondence with Carl Gustav Jung who was by then already an academically acclaimed researcher into word-association and the Galvanic Skin Response, and a lecturer at Zurich University, although still only an assistant to Eugen Bleuler at the Burghölzli Mental Hospital in Zürich.[76][77] In March 1907, Jung and Ludwig Binswanger, also a Swiss psychiatrist, travelled to Vienna to visit Freud and attend the discussion group. Thereafter, they established a small psychoanalytic group in Zürich. In 1908, reflecting its growing institutional status, the Wednesday group was reconstituted as the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society[78] with Freud as president, a position he relinquished in 1910 in favor of Adler in the hope of neutralizing his increasingly critical standpoint.[79]

The first woman member, Margarete Hilferding, joined the Society in 1910[80] and the following year she was joined by Tatiana Rosenthal and Sabina Spielrein who were both Russian psychiatrists and graduates of the Zürich University medical school. Before the completion of her studies, Spielrein had been a patient of Jung at the Burghölzli and the clinical and personal details of their relationship became the subject of an extensive correspondence between Freud and Jung. Both women would go on to make important contributions to the work of the Russian Psychoanalytic Society founded in 1910.[81]

Freud’s early followers met together formally for the first time at the Hotel Bristol, Salzburg on 27 April 1908. This meeting, which was retrospectively deemed to be the first International Psychoanalytic Congress,[82] was convened at the suggestion of Ernest Jones, then a London-based neurologist who had discovered Freud’s writings and begun applying psychoanalytic methods in his clinical work. Jones had met Jung at a conference the previous year and they met up again in Zürich to organize the Congress. There were, as Jones records, “forty-two present, half of whom were or became practicing analysts.”[83] In addition to Jones and the Viennese and Zürich contingents accompanying Freud and Jung, also present and notable for their subsequent importance in the psychoanalytic movement were Karl Abraham and Max Eitingon from Berlin, Sándor Ferenczi from Budapest and the New York-based Abraham Brill.

Important decisions were taken at the Congress to advance the impact of Freud’s work. A journal, the Jahrbuch für psychoanalytische und psychopathologishe Forschungen, was launched in 1909 under the editorship of Jung. This was followed in 1910 by the monthly Zentralblatt für Psychoanalyse edited by Adler and Stekel, in 1911 by Imago, a journal devoted to the application of psychoanalysis to the field of cultural and literary studies edited by Rank and in 1913 by the Internationale Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse, also edited by Rank.[84] Plans for an international association of psychoanalysts were put in place and these were implemented at the Nuremberg Congress of 1910 where Jung was elected, with Freud’s support, as its first president.

Freud turned to Brill and Jones to further his ambition to spread the psychoanalytic cause in the English-speaking world. Both were invited to Vienna following the Salzburg Congress and a division of labour was agreed with Brill given the translation rights for Freud’s works, and Jones, who was to take up a post at the University of Toronto later in the year, tasked with establishing a platform for Freudian ideas in North American academic and medical life.[85] Jones’s advocacy prepared the way for Freud’s visit to the United States, accompanied by Jung and Ferenczi, in September 1909 at the invitation of Stanley Hall, president of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, where he gave five lectures on psychoanalysis.[86]

The event, at which Freud was awarded an Honorary Doctorate, marked the first public recognition of Freud’s work and attracted widespread media interest. Freud’s audience included the distinguished neurologist and psychiatrist James Jackson Putnam, Professor of Diseases of the Nervous System at Harvard, who invited Freud to his country retreat where they held extensive discussions over a period of four days. Putnam’s subsequent public endorsement of Freud’s work represented a significant breakthrough for the psychoanalytic cause in the United States.[86] When Putnam and Jones organised the founding of the American Psychoanalytic Association in May 1911 they were elected president and secretary respectively. Brill founded the New York Psychoanalytic Society the same year. His English translations of Freud’s work began to appear from 1909.

Resignations from the IPA[edit source]

Some of Freud’s followers subsequently withdrew from the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) and founded their own schools.

From 1909, Adler’s views on topics such as neurosis began to differ markedly from those held by Freud. As Adler’s position appeared increasingly incompatible with Freudianism, a series of confrontations between their respective viewpoints took place at the meetings of the Viennese Psychoanalytic Society in January and February 1911. In February 1911, Adler, then the president of the society, resigned his position. At this time, Stekel also resigned from his position as vice president of the society. Adler finally left the Freudian group altogether in June 1911 to found his own organization with nine other members who had also resigned from the group.[87] This new formation was initially called Society for Free Psychoanalysis but it was soon renamed the Society for Individual Psychology. In the period after World War I, Adler became increasingly associated with a psychological position he devised called individual psychology.[88]The committee in 1922 (from left to right): Otto Rank, Sigmund Freud, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, Sándor Ferenczi, Ernest Jones, and Hanns Sachs

In 1912, Jung published Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido (published in English in 1916 as Psychology of the Unconscious) making it clear that his views were taking a direction quite different from those of Freud. To distinguish his system from psychoanalysis, Jung called it analytical psychology.[89] Anticipating the final breakdown of the relationship between Freud and Jung, Ernest Jones initiated the formation of a Secret Committee of loyalists charged with safeguarding the theoretical coherence and institutional legacy of the psychoanalytic movement. Formed in the autumn of 1912, the Committee comprised Freud, Jones, Abraham, Ferenczi, Rank, and Hanns Sachs. Max Eitingon joined the committee in 1919. Each member pledged himself not to make any public departure from the fundamental tenets of psychoanalytic theory before he had discussed his views with the others. After this development, Jung recognised that his position was untenable and resigned as editor of the Jarhbuch and then as president of the IPA in April 1914. The Zürich Society withdrew from the IPA the following July.[90]

Later the same year, Freud published a paper entitled “The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement“, the German original being first published in the Jahrbuch, giving his view on the birth and evolution of the psychoanalytic movement and the withdrawal of Adler and Jung from it.

The final defection from Freud’s inner circle occurred following the publication in 1924 of Rank’s The Trauma of Birth which other members of the committee read as, in effect, abandoning the Oedipus Complex as the central tenet of psychoanalytic theory. Abraham and Jones became increasingly forceful critics of Rank and though he and Freud were reluctant to end their close and long-standing relationship the break finally came in 1926 when Rank resigned from his official posts in the IPA and left Vienna for Paris. His place on the Committee was taken by Anna Freud.[91] Rank eventually settled in the United States where his revisions of Freudian theory were to influence a new generation of therapists uncomfortable with the orthodoxies of the IPA.

Early psychoanalytic movement[edit source]

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Psychoanalysis |

|---|

| showConcepts |

| showImportant figures |

| showImportant works |

| showSchools of thought |

| showTraining |

| showSee also |

| Psychology portal |

| vte |

After the founding of the IPA in 1910, an international network of psychoanalytical societies, training institutes, and clinics became well established and a regular schedule of biannual Congresses commenced after the end of World War I to coordinate their activities.[92]

Abraham and Eitingon founded the Berlin Psychoanalytic Society in 1910 and then the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute and the Poliklinik in 1920. The Poliklinik’s innovations of free treatment, and child analysis, and the Berlin Institute’s standardisation of psychoanalytic training had a major influence on the wider psychoanalytic movement. In 1927, Ernst Simmel founded the Schloss Tegel Sanatorium on the outskirts of Berlin, the first such establishment to provide psychoanalytic treatment in an institutional framework. Freud organised a fund to help finance its activities and his architect son, Ernst, was commissioned to refurbish the building. It was forced to close in 1931 for economic reasons.[93]

The 1910 Moscow Psychoanalytic Society became the Russian Psychoanalytic Society and Institute in 1922. Freud’s Russian followers were the first to benefit from translations of his work, the 1904 Russian translation of The Interpretation of Dreams appearing nine years before Brill’s English edition. The Russian Institute was unique in receiving state support for its activities, including publication of translations of Freud’s works.[94] Support was abruptly annulled in 1924, when Joseph Stalin came to power, after which psychoanalysis was denounced on ideological grounds.[95]

After helping found the American Psychoanalytic Association in 1911, Ernest Jones returned to Britain from Canada in 1913 and founded the London Psychoanalytic Society the same year. In 1919, he dissolved this organisation and, with its core membership purged of Jungian adherents, founded the British Psychoanalytical Society, serving as its president until 1944. The Institute of Psychoanalysis was established in 1924 and the London Clinic of Psychoanalysis was established in 1926, both under Jones’s directorship.[96]

The Vienna Ambulatorium (Clinic) was established in 1922 and the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute was founded in 1924 under the directorship of Helene Deutsch.[97] Ferenczi founded the Budapest Psychoanalytic Institute in 1913 and a clinic in 1929.

Psychoanalytic societies and institutes were established in Switzerland (1919), France (1926), Italy (1932), the Netherlands (1933), Norway (1933), and in Palestine (Jerusalem, 1933) by Eitingon, who had fled Berlin after Adolf Hitler came to power.[98] The New York Psychoanalytic Institute was founded in 1931.

The 1922 Berlin Congress was the last Freud attended.[99] By this time his speech had become seriously impaired by the prosthetic device he needed as a result of a series of operations on his cancerous jaw. He kept abreast of developments through regular correspondence with his principal followers and via the circular letters and meetings of the Secret Committee which he continued to attend.

The Committee continued to function until 1927 by which time institutional developments within the IPA, such as the establishment of the International Training Commission, had addressed concerns about the transmission of psychoanalytic theory and practice. There remained, however, significant differences over the issue of lay analysis – i.e. the acceptance of non-medically qualified candidates for psychoanalytic training. Freud set out his case in favour in 1926 in his The Question of Lay Analysis. He was resolutely opposed by the American societies who expressed concerns over professional standards and the risk of litigation (though child analysts were made exempt). These concerns were also shared by some of his European colleagues. Eventually, an agreement was reached allowing societies autonomy in setting criteria for candidature.[100]

In 1930, Freud received the Goethe Prize in recognition of his contributions to psychology and German literary culture.[101]

Patients[edit source]

Freud used pseudonyms in his case histories. Some patients known by pseudonyms were Cäcilie M. (Anna von Lieben); Dora (Ida Bauer, 1882–1945); Frau Emmy von N. (Fanny Moser); Fräulein Elisabeth von R. (Ilona Weiss);[102] Fräulein Katharina (Aurelia Kronich); Fräulein Lucy R.; Little Hans (Herbert Graf, 1903–1973); Rat Man (Ernst Lanzer, 1878–1914); Enos Fingy (Joshua Wild, 1878–1920);[103] and Wolf Man (Sergei Pankejeff, 1887–1979). Other famous patients included Prince Pedro Augusto of Brazil (1866–1934); H.D. (1886–1961); Emma Eckstein (1865–1924); Gustav Mahler (1860–1911), with whom Freud had only a single, extended consultation; Princess Marie Bonaparte; Edith Banfield Jackson (1895–1977);[104] Arthur Tansley (1871-1955), and Albert Hirst (1887–1974).[105]

Cancer[edit source]

In February 1923, Freud detected a leukoplakia, a benign growth associated with heavy smoking, on his mouth. He initially kept this secret, but in April 1923 he informed Ernest Jones, telling him that the growth had been removed. Freud consulted the dermatologist Maximilian Steiner, who advised him to quit smoking but lied about the growth’s seriousness, minimizing its importance. Freud later saw Felix Deutsch, who saw that the growth was cancerous; he identified it to Freud using the euphemism “a bad leukoplakia” instead of the technical diagnosis epithelioma. Deutsch advised Freud to stop smoking and have the growth excised. Freud was treated by Marcus Hajek, a rhinologist whose competence he had previously questioned. Hajek performed an unnecessary cosmetic surgery in his clinic’s outpatient department. Freud bled during and after the operation, and may narrowly have escaped death. Freud subsequently saw Deutsch again. Deutsch saw that further surgery would be required, but did not tell Freud he had cancer because he was worried that Freud might wish to commit suicide.[106]

Escape from Nazism[edit source]

In January 1933, the Nazi Party took control of Germany, and Freud’s books were prominent among those they burned and destroyed. Freud remarked to Ernest Jones: “What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now, they are content with burning my books.”[107] Freud continued to underestimate the growing Nazi threat and remained determined to stay in Vienna, even following the Anschluss of 13 March 1938, in which Nazi Germany annexed Austria, and the outbreaks of violent antisemitism that ensued.[108] Jones, the then president of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA), flew into Vienna from London via Prague on 15 March determined to get Freud to change his mind and seek exile in Britain. This prospect and the shock of the arrest and interrogation of Anna Freud by the Gestapo finally convinced Freud it was time to leave Austria.[108] Jones left for London the following week with a list provided by Freud of the party of émigrés for whom immigration permits would be required. Back in London, Jones used his personal acquaintance with the Home Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, to expedite the granting of permits. There were seventeen in all and work permits were provided where relevant. Jones also used his influence in scientific circles, persuading the president of the Royal Society, Sir William Bragg, to write to the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, requesting to good effect that diplomatic pressure be applied in Berlin and Vienna on Freud’s behalf. Freud also had support from American diplomats, notably his ex-patient and American ambassador to France, William Bullitt. Bullitt alerted U.S. President Roosevelt to the increased dangers facing the Freuds, resulting in the American consul-general in Vienna, John Cooper Wiley, arranging regular monitoring of Berggasse 19. He also intervened by phone call during the Gestapo interrogation of Anna Freud.[109]

The departure from Vienna began in stages throughout April and May 1938. Freud’s grandson, Ernst Halberstadt, and Freud’s son Martin’s wife and children left for Paris in April. Freud’s sister-in-law, Minna Bernays, left for London on 5 May, Martin Freud the following week and Freud’s daughter Mathilde and her husband, Robert Hollitscher, on 24 May.[110]

By the end of the month, arrangements for Freud’s own departure for London had become stalled, mired in a legally tortuous and financially extortionate process of negotiation with the Nazi authorities. Under regulations imposed on its Jewish population by the new Nazi regime, a Kommissar was appointed to manage Freud’s assets and those of the IPA whose headquarters were near Freud’s home. Freud was allocated to Dr. Anton Sauerwald, who had studied chemistry at Vienna University under Professor Josef Herzig, an old friend of Freud’s. Sauerwald read Freud’s books to further learn about him and became sympathetic towards his situation. Though required to disclose details of all Freud’s bank accounts to his superiors and to arrange the destruction of the historic library of books housed in the offices of the IPA, Sauerwald did neither. Instead, he removed evidence of Freud’s foreign bank accounts to his own safe-keeping and arranged the storage of the IPA library in the Austrian National Library, where it remained until the end of the war.[111]

Though Sauerwald’s intervention lessened the financial burden of the “flight” tax on Freud’s declared assets, other substantial charges were levied concerning the debts of the IPA and the valuable collection of antiquities Freud possessed. Unable to access his own accounts, Freud turned to Princess Marie Bonaparte, the most eminent and wealthy of his French followers, who had travelled to Vienna to offer her support, and it was she who made the necessary funds available.[112] This allowed Sauerwald to sign the necessary exit visas for Freud, his wife Martha, and daughter Anna. They left Vienna on the Orient Express on 4 June, accompanied by their housekeeper and a doctor, arriving in Paris the following day, where they stayed as guests of Marie Bonaparte, before travelling overnight to London, arriving at London Victoria station on 6 June.

Among those soon to call on Freud to pay their respects were Salvador Dalí, Stefan Zweig, Leonard Woolf, Virginia Woolf, and H. G. Wells. Representatives of the Royal Society called with the Society’s Charter for Freud, who had been elected a Foreign Member in 1936, to sign himself into membership. Marie Bonaparte arrived near the end of June to discuss the fate of Freud’s four elderly sisters left behind in Vienna. Her subsequent attempts to get them exit visas failed, and they would all die in Nazi concentration camps.[113]Freud’s last home, now dedicated to his life and work as the Freud Museum, 20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead, London NW3, England.

In early 1939, Sauerwald arrived in London in mysterious circumstances, where he met Freud’s brother Alexander.[114] He was tried and imprisoned in 1945 by an Austrian court for his activities as a Nazi Party official. Responding to a plea from his wife, Anna Freud wrote to confirm that Sauerwald “used his office as our appointed commissar in such a manner as to protect my father”. Her intervention helped secure his release from jail in 1947.[115]

In the Freuds’ new home, 20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead, North London, Freud’s Vienna consulting room was recreated in faithful detail. He continued to see patients there until the terminal stages of his illness. He also worked on his last books, Moses and Monotheism, published in German in 1938 and in English the following year[116] and the uncompleted An Outline of Psychoanalysis, which was published posthumously.

Death[edit source]

Freud’s ashes in the “Freud Corner” at the Golders Green Crematorium

By mid-September 1939, Freud’s cancer of the jaw was causing him increasingly severe pain and had been declared inoperable. The last book he read, Balzac‘s La Peau de chagrin, prompted reflections on his own increasing frailty, and a few days later he turned to his doctor, friend, and fellow refugee, Max Schur, reminding him that they had previously discussed the terminal stages of his illness: “Schur, you remember our ‘contract’ not to leave me in the lurch when the time had come. Now it is nothing but torture and makes no sense.” When Schur replied that he had not forgotten, Freud said, “I thank you,” and then, “Talk it over with Anna, and if she thinks it’s right, then make an end of it.” Anna Freud wanted to postpone her father’s death, but Schur convinced her it was pointless to keep him alive; on 21 and 22 September, he administered doses of morphine that resulted in Freud’s death at around 3 am on 23 September 1939.[117][118] However, discrepancies in the various accounts Schur gave of his role in Freud’s final hours, which have in turn led to inconsistencies between Freud’s main biographers, has led to further research and a revised account. This proposes that Schur was absent from Freud’s deathbed when a third and final dose of morphine was administered by Dr. Josephine Stross, a colleague of Anna Freud, leading to Freud’s death at around midnight on 23 September 1939.[119]

Three days after his death, Freud’s body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium in North London, with Harrods acting as funeral directors, on the instructions of his son, Ernst.[120] Funeral orations were given by Ernest Jones and the Austrian author Stefan Zweig. Freud’s ashes were later placed in the crematorium’s Ernest George Columbarium (see “Freud Corner”). They rest on a plinth designed by his son, Ernst,[121] in a sealed[120] ancient Greek bell krater painted with Dionysian scenes that Freud had received as a gift from Marie Bonaparte, and which he had kept in his study in Vienna for many years. After his wife, Martha, died in 1951, her ashes were also placed in the urn.[122]

Ideas[edit source]

Early work[edit source]

Freud began his study of medicine at the University of Vienna in 1873.[123] He took almost nine years to complete his studies, due to his interest in neurophysiological research, specifically investigation of the sexual anatomy of eels and the physiology of the fish nervous system, and because of his interest in studying philosophy with Franz Brentano. He entered private practice in neurology for financial reasons, receiving his M.D. degree in 1881 at the age of 25.[124] Amongst his principal concerns in the 1880s was the anatomy of the brain, specifically the medulla oblongata. He intervened in the important debates about aphasia with his monograph of 1891, Zur Auffassung der Aphasien, in which he coined the term agnosia and counselled against a too locationist view of the explanation of neurological deficits. Like his contemporary Eugen Bleuler, he emphasized brain function rather than brain structure.

Freud was also an early researcher in the field of cerebral palsy, which was then known as “cerebral paralysis”. He published several medical papers on the topic and showed that the disease existed long before other researchers of the period began to notice and study it. He also suggested that William John Little, the man who first identified cerebral palsy, was wrong about lack of oxygen during birth being a cause. Instead, he suggested that complications in birth were only a symptom.

Freud hoped that his research would provide a solid scientific basis for his therapeutic technique. The goal of Freudian therapy, or psychoanalysis, was to bring repressed thoughts and feelings into consciousness to free the patient from suffering repetitive distorted emotions.

Classically, the bringing of unconscious thoughts and feelings to consciousness is brought about by encouraging a patient to talk about dreams and engage in free association, in which patients report their thoughts without reservation and make no attempt to concentrate while doing so.[125] Another important element of psychoanalysis is transference, the process by which patients displace onto their analyst feelings and ideas which derive from previous figures in their lives. Transference was first seen as a regrettable phenomenon that interfered with the recovery of repressed memories and disturbed patients’ objectivity, but by 1912, Freud had come to see it as an essential part of the therapeutic process.[126]

The origin of Freud’s early work with psychoanalysis can be linked to Josef Breuer. Freud credited Breuer with opening the way to the discovery of the psychoanalytical method by his treatment of the case of Anna O. In November 1880, Breuer was called in to treat a highly intelligent 21-year-old woman (Bertha Pappenheim) for a persistent cough that he diagnosed as hysterical. He found that while nursing her dying father, she had developed some transitory symptoms, including visual disorders and paralysis and contractures of limbs, which he also diagnosed as hysterical. Breuer began to see his patient almost every day as the symptoms increased and became more persistent, and observed that she entered states of absence. He found that when, with his encouragement, she told fantasy stories in her evening states of absence her condition improved, and most of her symptoms had disappeared by April 1881. Following the death of her father in that month her condition deteriorated again. Breuer recorded that some of the symptoms eventually remitted spontaneously and that full recovery was achieved by inducing her to recall events that had precipitated the occurrence of a specific symptom.[127] In the years immediately following Breuer’s treatment, Anna O. spent three short periods in sanatoria with the diagnosis “hysteria” with “somatic symptoms”,[128] and some authors have challenged Breuer’s published account of a cure.[129][130][131] Richard Skues rejects this interpretation, which he sees as stemming from both Freudian and anti-psychoanalytical revisionism — revisionism that regards both Breuer’s narrative of the case as unreliable and his treatment of Anna O. as a failure.[132] Psychologist Frank Sulloway contends that “Freud’s case histories are rampant with censorship, distortions, highly dubious ‘reconstructions,’ and exaggerated claims.”[133]

Seduction theory[edit source]

In the early 1890s, Freud used a form of treatment based on the one that Breuer had described to him, modified by what he called his “pressure technique” and his newly developed analytic technique of interpretation and reconstruction. According to Freud’s later accounts of this period, as a result of his use of this procedure, most of his patients in the mid-1890s reported early childhood sexual abuse. He believed these accounts, which he used as the basis for his seduction theory, but then he came to believe that they were fantasies. He explained these at first as having the function of “fending off” memories of infantile masturbation, but in later years he wrote that they represented Oedipal fantasies, stemming from innate drives that are sexual and destructive in nature.[134]

Another version of events focuses on Freud’s proposing that unconscious memories of infantile sexual abuse were at the root of the psychoneuroses in letters to Fliess in October 1895, before he reported that he had actually discovered such abuse among his patients.[135] In the first half of 1896, Freud published three papers, which led to his seduction theory, stating that he had uncovered, in all of his current patients, deeply repressed memories of sexual abuse in early childhood.[136] In these papers, Freud recorded that his patients were not consciously aware of these memories, and must therefore be present as unconscious memories if they were to result in hysterical symptoms or obsessional neurosis. The patients were subjected to considerable pressure to “reproduce” infantile sexual abuse “scenes” that Freud was convinced had been repressed into the unconscious.[137] Patients were generally unconvinced that their experiences of Freud’s clinical procedure indicated actual sexual abuse. He reported that even after a supposed “reproduction” of sexual scenes the patients assured him emphatically of their disbelief.[138]

As well as his pressure technique, Freud’s clinical procedures involved analytic inference and the symbolic interpretation of symptoms to trace back to memories of infantile sexual abuse.[139] His claim of one hundred percent confirmation of his theory only served to reinforce previously expressed reservations from his colleagues about the validity of findings obtained through his suggestive techniques.[140] Freud subsequently showed inconsistency as to whether his seduction theory was still compatible with his later findings.[141] In an addendum to The Aetiology of Hysteria he stated: “All this is true [the sexual abuse of children], but it must be remembered that at the time I wrote it I had not yet freed myself from my overvaluation of reality and my low valuation of phantasy”.[142] Some years later Freud explicitly rejected the claim of his colleague Ferenczi that his patients’ reports of sexual molestation were actual memories instead of fantasies, and he tried to dissuade Ferenczi from making his views public.[141] Karin Ahbel-Rappe concludes in her study “‘I no longer believe’: did Freud abandon the seduction theory?”: “Freud marked out and started down a trail of investigation into the nature of the experience of infantile incest and its impact on the human psyche, and then abandoned this direction for the most part.”[143]

Cocaine[edit source]

As a medical researcher, Freud was an early user and proponent of cocaine as a stimulant as well as analgesic. He believed that cocaine was a cure for many mental and physical problems, and in his 1884 paper “On Coca” he extolled its virtues. Between 1883 and 1887 he wrote several articles recommending medical applications, including its use as an antidepressant. He narrowly missed out on obtaining scientific priority for discovering its anesthetic properties of which he was aware but had mentioned only in passing.[144] (Karl Koller, a colleague of Freud’s in Vienna, received that distinction in 1884 after reporting to a medical society the ways cocaine could be used in delicate eye surgery.) Freud also recommended cocaine as a cure for morphine addiction.[145] He had introduced cocaine to his friend Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow, who had become addicted to morphine taken to relieve years of excruciating nerve pain resulting from an infection acquired after injuring himself while performing an autopsy. His claim that Fleischl-Marxow was cured of his addiction was premature, though he never acknowledged that he had been at fault. Fleischl-Marxow developed an acute case of “cocaine psychosis”, and soon returned to using morphine, dying a few years later still suffering from intolerable pain.[146]

The application as an anesthetic turned out to be one of the few safe uses of cocaine, and as reports of addiction and overdose began to filter in from many places in the world, Freud’s medical reputation became somewhat tarnished.[147] After the “Cocaine Episode”[148] Freud ceased to publicly recommend the use of the drug, but continued to take it himself occasionally for depression, migraine and nasal inflammation during the early 1890s, before discontinuing its use in 1896.[149]

The unconscious[edit source]

Main article: Unconscious mind

The concept of the unconscious was central to Freud’s account of the mind. Freud believed that while poets and thinkers had long known of the existence of the unconscious, he had ensured that it received scientific recognition in the field of psychology.[150]

Freud states explicitly that his concept of the unconscious as he first formulated it was based on the theory of repression. He postulated a cycle in which ideas are repressed, but remain in the mind, removed from consciousness yet operative, then reappear in consciousness under certain circumstances. The postulate was based upon the investigation of cases of hysteria, which revealed instances of behaviour in patients that could not be explained without reference to ideas or thoughts of which they had no awareness and which analysis revealed were linked to the (real or imagined) repressed sexual scenarios of childhood. In his later re-formulations of the concept of repression in his 1915 paper ‘Repression’ (Standard Edition XIV) Freud introduced the distinction in the unconscious between primary repression linked to the universal taboo on incest (‘innately present originally’) and repression (‘after expulsion’) that was a product of an individual’s life history (‘acquired in the course of the ego’s development’) in which something that was at one point conscious is rejected or eliminated from consciousness.[150]

In his account of the development and modification of his theory of unconscious mental processes he sets out in his 1915 paper ‘The Unconscious’ (Standard Edition XIV), Freud identifies the three perspectives he employs: the dynamic, the economic and the topographical.

The dynamic perspective concerns firstly the constitution of the unconscious by repression and secondly the process of “censorship” which maintains unwanted, anxiety-inducing thoughts as such. Here Freud is drawing on observations from his earliest clinical work in the treatment of hysteria.

In the economic perspective the focus is upon the trajectories of the repressed contents “the vicissitudes of sexual impulses” as they undergo complex transformations in the process of both symptom formation and normal unconscious thought such as dreams and slips of the tongue. These were topics Freud explored in detail in The Interpretation of Dreams and The Psychopathology of Everyday Life.

Whereas both these former perspectives focus on the unconscious as it is about to enter consciousness, the topographical perspective represents a shift in which the systemic properties of the unconscious, its characteristic processes, and modes of operation such as condensation and displacement, are placed in the foreground.

This “first topography” presents a model of psychic structure comprising three systems:

- The System Ucs – the unconscious: “primary process” mentation governed by the pleasure principle characterised by “exemption from mutual contradiction, … mobility of cathexes, timelessness, and replacement of external by psychical reality.” (‘The Unconscious’ (1915) Standard Edition XIV).

- The System Pcs – the preconscious in which the unconscious thing-presentations of the primary process are bound by the secondary processes of language (word presentations), a prerequisite for their becoming available to consciousness.

- The System Cns – conscious thought governed by the reality principle.

In his later work, notably in The Ego and the Id (1923), a second topography is introduced comprising id, ego and super-ego, which is superimposed on the first without replacing it.[151] In this later formulation of the concept of the unconscious the id[152] comprises a reservoir of instincts or drives a portion of them being hereditary or innate, a portion repressed or acquired. As such, from the economic perspective, the id is the prime source of psychical energy and from the dynamic perspective it conflicts with the ego[153] and the super-ego[154] which, genetically speaking, are diversifications of the id.

Dreams[edit source]

Main article: The Interpretation of Dreams

Freud believed the function of dreams is to preserve sleep by representing as fulfilled wishes that would otherwise awaken the dreamer.[155]

In Freud’s theory dreams are instigated by the daily occurrences and thoughts of everyday life. In what Freud called the “dream-work”, these “secondary process” thoughts (“word presentations”), governed by the rules of language and the reality principle, become subject to the “primary process” of unconscious thought (“thing presentations”) governed by the pleasure principle, wish gratification and the repressed sexual scenarios of childhood. Because of the disturbing nature of the latter and other repressed thoughts and desires which may have become linked to them, the dream-work operates a censorship function, disguising by distortion, displacement, and condensation the repressed thoughts to preserve sleep.[156]

In the clinical setting, Freud encouraged free association to the dream’s manifest content, as recounted in the dream narrative, to facilitate interpretative work on its latent content – the repressed thoughts and fantasies – and also on the underlying mechanisms and structures operative in the dream-work. As Freud developed his theoretical work on dreams he went beyond his theory of dreams as wish-fulfillments to arrive at an emphasis on dreams as “nothing other than a particular form of thinking. … It is the dream-work that creates that form, and it alone is the essence of dreaming”.[157]

Psychosexual development[edit source]

Main article: Psychosexual development

Freud’s theory of psychosexual development proposes that following on from the initial polymorphous perversity of infantile sexuality, the sexual “drives” pass through the distinct developmental phases of the oral, the anal, and the phallic. Though these phases then give way to a latency stage of reduced sexual interest and activity (from the age of five to puberty, approximately), they leave, to a greater or lesser extent, a “perverse” and bisexual residue which persists during the formation of adult genital sexuality. Freud argued that neurosis and perversion could be explained in terms of fixation or regression to these phases whereas adult character and cultural creativity could achieve a sublimation of their perverse residue.[158]

After Freud’s later development of the theory of the Oedipus complex this normative developmental trajectory becomes formulated in terms of the child’s renunciation of incestuous desires under the fantasised threat of (or fantasised fact of, in the case of the girl) castration.[159] The “dissolution” of the Oedipus complex is then achieved when the child’s rivalrous identification with the parental figure is transformed into the pacifying identifications of the Ego ideal which assume both similarity and difference and acknowledge the separateness and autonomy of the other.[160]

Freud hoped to prove that his model was universally valid and turned to ancient mythology and contemporary ethnography for comparative material arguing that totemism reflected a ritualized enactment of a tribal Oedipal conflict.[161]

Id, ego, and super-ego[edit source]

Main article: Id, ego and super-egoThe iceberg metaphor is often used to explain the psyche’s parts in relation to one another

Freud proposed that the human psyche could be divided into three parts: Id, ego, and super-ego. Freud discussed this model in the 1920 essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle, and fully elaborated upon it in The Ego and the Id (1923), in which he developed it as an alternative to his previous topographic schema (i.e., conscious, unconscious and preconscious). The id is the completely unconscious, impulsive, childlike portion of the psyche that operates on the “pleasure principle” and is the source of basic impulses and drives; it seeks immediate pleasure and gratification.[162]

Freud acknowledged that his use of the term Id (das Es, “the It”) derives from the writings of Georg Groddeck.[152][163] The super-ego is the moral component of the psyche.[154] The rational ego attempts to exact a balance between the impractical hedonism of the id and the equally impractical moralism of the super-ego;[153] it is the part of the psyche that is usually reflected most directly in a person’s actions. When overburdened or threatened by its tasks, it may employ defence mechanisms including denial, repression, undoing, rationalization, and displacement. This concept is usually represented by the “Iceberg Model”.[164] This model represents the roles the id, ego, and super- ego play in relation to conscious and unconscious thought.

Freud compared the relationship between the ego and the id to that between a charioteer and his horses: the horses provide the energy and drive, while the charioteer provides direction.[162]

Life and death drives[edit source]

Main articles: Libido, Death drive, and Repetition compulsion

Freud believed that the human psyche is subject to two conflicting drives: the life drive or libido and the death drive. The life drive was also termed “Eros” and the death drive “Thanatos”, although Freud did not use the latter term; “Thanatos” was introduced in this context by Paul Federn.[165][166] Freud hypothesized that libido is a form of mental energy with which processes, structures, and object-representations are invested.[167]

In Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), Freud inferred the existence of a death drive. Its premise was a regulatory principle that has been described as “the principle of psychic inertia”, “the Nirvana principle”,[168] and “the conservatism of instinct”. Its background was Freud’s earlier Project for a Scientific Psychology, where he had defined the principle governing the mental apparatus as its tendency to divest itself of quantity or to reduce tension to zero. Freud had been obliged to abandon that definition, since it proved adequate only to the most rudimentary kinds of mental functioning, and replaced the idea that the apparatus tends toward a level of zero tension with the idea that it tends toward a minimum level of tension.[169]

Freud in effect readopted the original definition in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, this time applying it to a different principle. He asserted that on certain occasions the mind acts as though it could eliminate tension, or in effect to reduce itself to a state of extinction; his key evidence for this was the existence of the compulsion to repeat. Examples of such repetition included the dream life of traumatic neurotics and children’s play. In the phenomenon of repetition, Freud saw a psychic trend to work over earlier impressions, to master them and derive pleasure from them, a trend that was before the pleasure principle but not opposed to it. In addition to that trend, there was also a principle at work that was opposed to, and thus “beyond” the pleasure principle. If repetition is a necessary element in the binding of energy or adaptation, when carried to inordinate lengths it becomes a means of abandoning adaptations and reinstating earlier or less evolved psychic positions. By combining this idea with the hypothesis that all repetition is a form of discharge, Freud concluded that the compulsion to repeat is an effort to restore a state that is both historically primitive and marked by the total draining of energy: death.[169] Such an explanation has been defined by some scholars as “metaphysical biology”.[170]

Melancholia[edit source]

In his 1917 essay “Mourning and Melancholia”, Freud distinguished mourning, painful but an inevitable part of life, and “melancholia”, his term for pathological refusal of a mourner to “decathect” from the lost one. Freud claimed that, in normal mourning, the ego was responsible for narcissistically detaching the libido from the lost one as a means of self-preservation, but that in “melancholia”, prior ambivalence towards the lost one prevents this from occurring. Suicide, Freud hypothesized, could result in extreme cases, when unconscious feelings of conflict became directed against the mourner’s own ego.[171][172]

Femininity and female sexuality[edit source]

Freud’s account of femininity is grounded in his theory of psychic development as it traces the uneven transition from the earliest stages of infantile and childhood sexuality characterised by polymorphous perversity and a bisexual disposition through to the fantasy scenarios and rivalrous identifications of the Oedipus complex on to the greater or lesser extent these are modified in adult sexuality. There are different trajectories for the boy and the girl which arise as effects of the castration complex. Anatomical difference, the possession of a penis, induces castration anxiety for the boy whereas the girl experiences a sense of deprivation. In the boy’s case the castration complex concludes the Oedipal phase whereas for the girl it precipitates it.[173]

The constraint of the erotic feelings and fantasies of the girl and her turn away from the mother to the father is an uneven and precarious process entailing “waves of repression”. The normal outcome is, according to Freud, the vagina becoming “the new leading zone” of sexual sensitivity displacing the previously dominant clitoris the phallic properties of which made it indistinguishable in the child’s early sexual life from the penis. This leaves a legacy of penis envy and emotional ambivalence for the girl which was “intimately related the essence of femininity” and leads to “the greater proneness of women to neurosis and especially hysteria.”[174] In his last paper on the topic Freud likewise concludes that “the development of femininity remains exposed to disturbance by the residual phenomena of the early masculine period… Some portion of what we men call the ‘enigma of women’ may perhaps be derived from this expression of bisexuality in women’s lives.”[175]

Initiating what became the first debate within psychoanalysis on femininity, Karen Horney of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute set out to challenge Freud’s account of femininity. Rejecting Freud’s theories of the feminine castration complex and penis envy, Horney argued for a primary femininity and penis envy as a defensive formation rather than arising from the fact, or “injury”, of biological asymmetry as Freud held. Horney had the influential support of Melanie Klein and Ernest Jones who coined the term “phallocentrism” in his critique of Freud’s position.[176]

In defending Freud against this critique, feminist scholar Jacqueline Rose has argued that it presupposes a more normative account of female sexual development than that given by Freud. She finds that Freud moved from a description of the little girl stuck with her ‘inferiority’ or ‘injury’ in the face of the anatomy of the little boy to an account in his later work which explicitly describes the process of becoming ‘feminine’ as an ‘injury’ or ‘catastrophe’ for the complexity of her earlier psychic and sexual life.[177]

Throughout his deliberations on what he described as the “dark continent” of female sexuality and the “riddle” of femininity, Freud was careful to emphasise the “average validity” and provisional nature of his findings.[178] He did, however, in response to his critics, maintain a steadfast objection “to all of you … to the extent that you do not distinguish more clearly between what is psychic and what is biological…”[179]

Religion[edit source]

Main article: Freud and religion

Freud regarded the monotheistic God as an illusion based upon the infantile emotional need for a powerful, supernatural pater familias. He maintained that religion – once necessary to restrain man’s violent nature in the early stages of civilization – in modern times, can be set aside in favor of reason and science.[180] “Obsessive Actions and Religious Practices” (1907) notes the likeness between faith (religious belief) and neurotic obsession.[181] Totem and Taboo (1913) proposes that society and religion begin with the patricide and eating of the powerful paternal figure, who then becomes a revered collective memory.[182] These arguments were further developed in The Future of an Illusion (1927) in which Freud argued that religious belief serves the function of psychological consolation. Freud argues the belief of a supernatural protector serves as a buffer from man’s “fear of nature” just as the belief in an afterlife serves as a buffer from man’s fear of death. The core idea of the work is that all of religious belief can be explained through its function to society, not for its relation to the truth. This is why, according to Freud, religious beliefs are “illusions”. In Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), he quotes his friend Romain Rolland, who described religion as an “oceanic sensation”, but says he never experienced this feeling.[183] Moses and Monotheism (1937) proposes that Moses was the tribal pater familias, killed by the Jews, who psychologically coped with the patricide with a reaction formation conducive to their establishing monotheistic Judaism;[184][185] analogously, he described the Roman Catholic rite of Holy Communion as cultural evidence of the killing and devouring of the sacred father.[116][186]

Moreover, he perceived religion, with its suppression of violence, as mediator of the societal and personal, the public and the private, conflicts between Eros and Thanatos, the forces of life and death.[187] Later works indicate Freud’s pessimism about the future of civilization, which he noted in the 1931 edition of Civilization and its Discontents.[188]

In a footnote of his 1909 work, Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-year-old Boy, Freud theorized that the universal fear of castration was provoked in the uncircumcised when they perceived circumcision and that this was “the deepest unconscious root of anti-Semitism“.[189]

Legacy[edit source]

The 1971 Sigmund Freud memorial in Hampstead, North London, by Oscar Nemon, is located near to where Sigmund and Anna Freud lived, now the Freud Museum. The building behind the statue is the Tavistock Clinic, a major psychological health care institution.

Freud’s legacy, though a highly contested area of controversy, has been assessed as “one of the strongest influences on twentieth-century thought, its impact comparable only to that of Darwinism and Marxism,”[190] with its range of influence permeating “all the fields of culture … so far as to change our way of life and concept of man.”[191]

Psychotherapy[edit source]

Though not the first methodology in the practice of individual verbal psychotherapy,[192] Freud’s psychoanalytic system came to dominate the field from early in the twentieth century, forming the basis for many later variants. While these systems have adopted different theories and techniques, all have followed Freud by attempting to achieve psychic and behavioral change through having patients talk about their difficulties.[4] Psychoanalysis is not as influential as it once was in Europe and the United States, though in some parts of the world, notably Latin America, its influence in the later 20th century expanded substantially. Psychoanalysis also remains influential within many contemporary schools of psychotherapy and has led to innovative therapeutic work in schools and with families and groups.[193] There is a substantial body of research which demonstrates the efficacy of the clinical methods of psychoanalysis[194] and of related psychodynamic therapies in treating a wide range of psychological disorders.[195]

The neo-Freudians, a group including Alfred Adler, Otto Rank, Karen Horney, Harry Stack Sullivan and Erich Fromm, rejected Freud’s theory of instinctual drive, emphasized interpersonal relations and self-assertiveness, and made modifications to therapeutic practice that reflected these theoretical shifts. Adler originated the approach, although his influence was indirect due to his inability to systematically formulate his ideas. The neo-Freudian analysis places more emphasis on the patient’s relationship with the analyst and less on the exploration of the unconscious.[196]

Carl Jung believed that the collective unconscious, which reflects the cosmic order and the history of the human species, is the most important part of the mind. It contains archetypes, which are manifested in symbols that appear in dreams, disturbed states of mind, and various products of culture. Jungians are less interested in infantile development and psychological conflict between wishes and the forces that frustrate them than in integration between different parts of the person. The object of Jungian therapy was to mend such splits. Jung focused in particular on problems of middle and later life. His objective was to allow people to experience the split-off aspects of themselves, such as the anima (a man’s suppressed female self), the animus (a woman’s suppressed male self), or the shadow (an inferior self-image), and thereby attain wisdom.[196]

Jacques Lacan approached psychoanalysis through linguistics and literature. Lacan believed Freud’s essential work had been done before 1905 and concerned the interpretation of dreams, neurotic symptoms, and slips, which had been based on a revolutionary way of understanding language and its relation to experience and subjectivity, and that ego psychology and object relations theory were based upon misreadings of Freud’s work. For Lacan, the determinative dimension of human experience is neither the self (as in ego psychology) nor relations with others (as in object relations theory), but language. Lacan saw desire as more important than need and considered it necessarily ungratifiable.[197]

Wilhelm Reich developed ideas that Freud had developed at the beginning of his psychoanalytic investigation but then superseded but never finally discarded. These were the concept of the Actualneurosis and a theory of anxiety based upon the idea of dammed-up libido. In Freud’s original view, what really happened to a person (the “actual”) determined the resulting neurotic disposition. Freud applied that idea both to infants and to adults. In the former case, seductions were sought as the causes of later neuroses and in the latter incomplete sexual release. Unlike Freud, Reich retained the idea that actual experience, especially sexual experience, was of key significance. By the 1920s, Reich had “taken Freud’s original ideas about sexual release to the point of specifying the orgasm as the criteria of healthy function.” Reich was also “developing his ideas about character into a form that would later take shape, first as “muscular armour”, and eventually as a transducer of universal biological energy, the “orgone”.”[196]