-

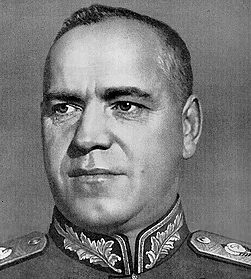

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

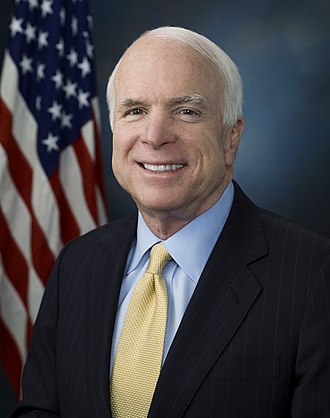

Kemal Atatürk[2] (or alternatively written as Kamâl Atatürk,[3] Mustafa Kemal Pasha[a] until 1934, commonly referred to as Mustafa Kemal Atatürk;[b] c. 1881[c] – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish field marshal, revolutionary statesman, author, and the founding father of the Republic of Turkey, serving as its first president from 1923 until his death in 1938. He undertook sweeping progressive reforms, which modernized Turkey into a secular, industrializing nation.[4][5][6][7] Ideologically a secularist and nationalist, his policies and socio-political theories became known as Kemalism.[4] Due to his military and political accomplishments, Atatürk is regarded as one of the most important political leaders of the 20th century.[8]

Atatürk came to prominence for his role in securing the Ottoman Turkish victory at the Battle of Gallipoli (1915) during World War I.[9] Following the defeat and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, he led the Turkish National Movement, which resisted mainland Turkey’s partition among the victorious Allied powers. Establishing a provisional government in the present-day Turkish capital Ankara (known in English at the time as Angora), he defeated the forces sent by the Allies, thus emerging victorious from what was later referred to as the Turkish War of Independence. He subsequently proceeded to abolish the decrepit Ottoman Empire and proclaimed the foundation of the Turkish Republic in its place.

As the president of the newly formed Turkish Republic, Atatürk initiated a rigorous program of political, economic, and cultural reforms with the ultimate aim of building a modern, progressive and secular nation-state. He made primary education free and compulsory, opening thousands of new schools all over the country. He also introduced the Latin-based Turkish alphabet, replacing the old Ottoman Turkish alphabet. Turkish women received equal civil and political rights during Atatürk’s presidency.[10] In particular, women were given voting rights in local elections by Act no. 1580 on 3 April 1930 and a few years later, in 1934, full universal suffrage.[11]

His government carried out a policy of Turkification, trying to create a homogeneous and unified nation.[12][13][14] Under Atatürk, non-Turkish minorities were pressured to speak Turkish in public;[15] non-Turkish toponyms and last names of minorities had to be changed to Turkish renditions.[16][17] The Turkish Parliament granted him the surname Atatürk in 1934, which means “Father of the Turks”, in recognition of the role he played in building the modern Turkish Republic.[18] He died on 10 November 1938 at Dolmabahçe Palace in Istanbul, at the age of 57;[19] he was succeeded as President by his long-time Prime Minister İsmet İnönü[20] and was honored with a state funeral. His iconic mausoleum in Ankara, built and opened in 1953, is surrounded by a park called the Peace Park in honor of his famous expression “Peace at Home, Peace in the World“.

In 1981, the centennial of Atatürk’s birth, his memory was honoured by the United Nations and UNESCO, which declared it The Atatürk Year in the World and adopted the Resolution on the Atatürk Centennial, describing him as “the leader of the first struggle given against colonialism and imperialism” and a “remarkable promoter of the sense of understanding between peoples and durable peace between the nations of the world and that he worked all his life for the development of harmony and cooperation between peoples without distinction”.[21][22] Atatürk is commemorated by many memorials and places named in his honor in Turkey and throughout the world.

Contents

- 1Early life

- 2Military career

- 3Presidency

- 3.1Domestic policies

- 3.1.1Emergence of the state, 1923–1924

- 3.1.2Civic independence and the Caliphate, 1924–1925

- 3.1.3Educational reform

- 3.1.4Western attire

- 3.1.5Religious insignia

- 3.1.6Opposition to Atatürk in 1924–1927

- 3.1.7Modernization efforts, 1926–1930

- 3.1.8Opposition to Atatürk in 1930–1931

- 3.1.9Modernization efforts, 1931–1938

- 3.1.10Unification and nationalisation efforts

- 3.2Foreign policies

- 3.3Economic policies

- 3.1Domestic policies

- 4Personal life

- 5Illness and death

- 6Legacy

- 7Awards and decorations

- 8See also

- 9Notes

- 10References

- 11Bibliography

- 12External links

Early life

Further information: Personal life of Mustafa Kemal AtatürkThe house where Atatürk was born in the Ottoman city of Salonika (Thessaloniki in present-day Greece), now a museumThe reconstructed house of Atatürk’s paternal grandparents, in the Ottoman village of Kocacık (Kodžadžik in present-day North Macedonia)

Kemal Atatürk was born (under the name Ali Rıza oğlu Mustafa which means “Mustafa son of Ali Rıza”) in the early months of 1881, either in the Ahmet Subaşı neighbourhood or at a house (preserved as a museum) in Islahhane Street (now Apostolou Pavlou Street) in the Koca Kasım Pasha neighbourhood in Salonica (Selanik),[23] Ottoman Empire (Thessaloniki in present-day Greece). His parents were Ali Rıza Efendi, a militia officer originally from Kodžadžik, title deed clerk and lumber trader, and Zübeyde Hanım. Only one of Mustafa’s siblings, a sister named Makbule (Atadan) survived childhood; she died in 1956.[24] According to Andrew Mango, his family was Muslim, Turkish-speaking and precariously middle-class.[25] His father Ali Rıza is thought to have been of Albanian origin by some authors;[26][27][28] however, according to Falih Rıfkı Atay, Vamık D. Volkan, Norman Itzkowitz, Müjgân Cunbur, Numan Kartal and Hasan İzzettin Dinamo, Ali Rıza’s ancestors were Turks, ultimately descending from Söke in the Aydın Province of Anatolia.[29][30][31][32][33][34] His mother Zübeyde is thought to have been of Turkish origin,[27][28] and according to Şevket Süreyya Aydemir, she was of Yörük ancestry.[35] According to other sources, he was Jewish (Scholem, 2007) or Bulgarian (Tončeva, 2009).[36] Due to the large Jewish community of Salonica in the Ottoman period, many of the Islamist opponents who were disturbed by his reforms claimed that Atatürk had Dönmeh ancestors, that is Jews who converted to Islam publicly, but still secretly retained their belief in Judaism.[37]

He was born Mustafa, and his second name Kemal (meaning Perfection or Maturity) was given to him by his mathematics teacher, Captain Üsküplü Mustafa Efendi, “in admiration of his capability and maturity” according to Afet İnan,[38][39] and, according to other sources because his teacher wanted to distinguish his student who had the same name as him,[40][41] although biographer Andrew Mango suggests that he may have chosen the name himself as a tribute to the nationalist poet Namık Kemal.[42] In his early years, his mother encouraged Atatürk to attend a religious school, something he did reluctantly and only briefly. Later, he attended the Şemsi Efendi School (a private school with a more secular curriculum) at the direction of his father. When he was seven years old, his father died.[43] His mother wanted him to learn a trade, but without consulting them, Atatürk took the entrance exam for the Salonica Military School (Selanik Askeri Rüştiyesi) in 1893. In 1896, he enrolled in the Monastir Military High School (in modern Bitola, North Macedonia). On 14 March 1899,[44] he enrolled at the Ottoman Military Academy in the neighbourhood of Pangaltı[45] within the Şişli district of the Ottoman capital city Constantinople (modern Istanbul) and graduated in 1902. He later graduated from the Ottoman Military College in Constantinople on 11 January 1905.[44]

Military career

Main article: Military career of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Early years

See also: Vatan ve Hürriyet, Committee of Union and Progress, and Young Turk RevolutionAtatürk on the day of graduation from the War Academy in 1905

Shortly after graduation, he was arrested by the police for his anti-monarchist activities. Following confinement for several months he was released only with the support of Rıza Pasha, his former school director.[46] After his release, Atatürk was assigned to the Fifth Army based in Damascus as a Staff Captain[44] in the company of Ali Fuat (Cebesoy) and Lütfi Müfit (Özdeş).[47] He joined a small secret revolutionary society of reformist officers led by a merchant Mustafa Elvan (Cantekin) called Vatan ve Hürriyet (“Motherland and Liberty”). On 20 June 1907, he was promoted to the rank of Senior Captain (Kolağası) and on 13 October 1907, was assigned to the headquarters of the Third Army in Manastır.[48] He joined the Committee of Union and Progress, with membership number 322, although in later years he became known for his opposition to, and frequent criticism of, the policies pursued by the CUP leadership. On 22 June 1908, he was appointed the Inspector of the Ottoman Railways in Eastern Rumelia (Doğu Rumeli Bölgesi Demiryolları Müfettişi).[48] In July 1908, he played a role in the Young Turk Revolution which seized power from Sultan Abdülhamid II and restored the constitutional monarchy.Atatürk (front row, second from left) with the Ottoman Turkish observers at the Picardie army manoeuvres in France, 28 September 1910

He was proposing depoliticization in the army, a proposal which was disliked by the leaders of the CUP. As a result, he was sent away to Tripolitania Vilayet (present Libya, then an Ottoman territory) under the pretext of suppressing a tribal rebellion towards the end of 1908.[46] According to Mikush however, he volunteered for this mission.[49] He suppressed the revolt and returned to Constantinople in January 1909.

In April 1909 in Constantinople, a group of soldiers began a counter-revolution (see 31 March Incident). Atatürk was instrumental in suppressing the revolt.[50]

In 1910, he was called to the Ottoman provinces in Albania.[51][52] At that time Isa Boletini was leading Albanian uprisings in Kosovo, and there were revolts in Albania as well.[53][54] In 1910, Atatürk met with Eqrem Vlora, the Albanian lord, politician, writer, and one of the delegates of the Albanian Declaration of Independence.[55][56]

Later, in the autumn of 1910, he was among the Ottoman military observers who attended the Picardie army manoeuvres in France,[57] and in 1911, served at the Ministry of War (Harbiye Nezareti) in Constantinople for a short time.

Italo-Turkish War (1911–12)

Main article: Italo-Turkish WarSee also: Battle of Tobruk (1911)Atatürk (left) with an Ottoman military officer and Bedouin forces in Derna, Tripolitania Vilayet, 1912

In 1911, he volunteered to fight in the Italo-Turkish War[58] in the Ottoman Tripolitania Vilayet (present-day Libya).[59] He served mainly in the areas near Derna and Tobruk.[58] The invading Italian army had a strength of 150,000 men;[60] it was opposed by 20,000 Bedouins and 8,000 Turks.[61] A short time before Italy declared war, many of the Ottoman troops in Libya were sent to the Ottoman province of Yemen Vilayet to put down the rebellion there, so the Ottoman government was caught with inadequate resources to counter the Italians in Libya. Britain, which controlled the Ottoman provinces of Egypt and Sudan, did not allow additional Ottoman troops to reach Libya through Egypt. Ottoman soldiers like Atatürk went to Libya either dressed as Arabs (risking imprisonment if noticed by the British authorities in Egypt) or by the very few available ferries (the Italians, who had superior naval forces, effectively controlled the sea routes to Tripoli). However, despite all the hardships, Atatürk’s forces in Libya managed to repel the Italians on a number of occasions, such as at the Battle of Tobruk on 22 December 1911.

During the Battle of Derna on 16–17 January 1912, while Atatürk was assaulting the Italian-controlled fortress of Kasr-ı Harun, two Italian planes dropped bombs on the Ottoman forces; a limestone splinter from a damaged building’s rubble struck Atatürk’s left eye, causing permanent tissue damage, but not total loss of sight. He received medical treatment for nearly a month; he attempted to leave the Red Crescent‘s health facilities after only two weeks, but when his eye’s situation worsened, he had to return and resume treatment. On 6 March 1912, Atatürk became the Commander of the Ottoman forces in Derna. He managed to defend and retain the city and its surrounding region until the end of the Italo-Turkish War on 18 October 1912. Atatürk, Enver Bey, Fethi Bey, and the other Ottoman military commanders in Libya had to return to Ottoman Europe following the outbreak of the Balkan Wars on 8 October 1912. Having lost the war, the Ottoman government had to surrender Tripolitania, Fezzan, and Cyrenaica (three provinces forming present-day Libya) to the Kingdom of Italy in the Treaty of Lausanne (1912) signed ten days later, on 18 October 1912 (since 1923, historians have preferred to name this treaty as the “Treaty of Ouchy”, after the Château d’Ouchy in Lausanne where it was signed, to distinguish it from the later Treaty of Lausanne (1923) signed between the Allies of World War I and the Grand National Assembly of Turkey in Ankara (at that time known as Angora).[62]

Balkan Wars (1912–13)

Main article: Balkan WarsSee also: First Balkan War and Second Balkan War

On 1 December 1912, Atatürk arrived at his new headquarters on the Gallipoli peninsula and, during the First Balkan War, he took part in the amphibious landing at Bulair on the coast of Thrace under Binbaşı Fethi Bey, but this offensive was repulsed during the Battle of Bulair by Georgi Todorov‘s 7th Rila Infantry Division[63] under the command of Stiliyan Kovachev‘s Bulgarian Fourth Army.[64]

In June 1913, during the Second Balkan War, he took part in the Ottoman Army forces[65] commanded by Kaymakam Enver Bey that recovered Dimetoka and Edirne (Adrianople, the capital city of the Ottoman Empire between 1365 and 1453, thus of utmost historic importance for the Turks) together with most of eastern Thrace from the Bulgarians.

In 1913, he was appointed the Ottoman military attaché to all Balkan states (his office was in Sofia, Bulgaria) and promoted to the rank of Kaymakam (Lieutenant Colonel / Colonel) on 1 March 1914.[44] While in Bulgaria, he met with Dimitrina Kovacheva, the daughter of Bulgarian general Stiliyan Kovachev (against whose forces he had fought during the Balkan Wars), who had recently completed her education in Switzerland, during a New Year’s Eve ball in Sofia and fell in love with her.[66] The two danced at the ball and started to secretly date in the following days.[66] Atatürk twice asked Dimitrina’s parents for their permission to marry her (the second time was in 1915, during World War I) and was twice refused, which left him with a lifelong sadness.[66]

First World War (1914–18)

Main article: World War ISee also: Gallipoli Campaign and Middle Eastern theatre of World War ICevat Pasha and Atatürk on the daily Tasvîr-i Efkâr [tr] dated 29 October 1915

In 1914, the Ottoman Empire entered the European and Middle Eastern theatres of World War I allied with the Central Powers. Atatürk was given the task of organizing and commanding the 19th Division attached to the Fifth Army during the Battle of Gallipoli. He became the front-line commander after correctly anticipating where the Allies would attack, and held his position until they retreated. Following the Battle of Gallipoli, Atatürk served in Edirne until 14 January 1916. He was then assigned to the command of the XVI Corps of the Second Army and sent to the Caucasus Campaign after the massive Russian offensive had reached key Anatolian cities. On 7 August, he rallied his troops and mounted a counteroffensive.[67] Two of his divisions captured Bitlis and Muş, upsetting the calculations of the Russian Command.[68]Atatürk with Ottoman military officers during the Battle of Gallipoli, Çanakkale, 1915

Following this victory, the CUP government in Constantinople proposed to establish a new army in Hejaz (Hicaz Kuvve-i Seferiyesi) and appoint Atatürk to its command, but he refused the proposal and this army was never established.[57] Instead, on 7 March 1917, Atatürk was promoted from the command of the XVI Corps to the overall command of the Second Army, although the Czar’s armies were soon withdrawn when the Russian Revolution erupted.[57][67]

In July 1917, he was appointed to the command of the Seventh Army, replacing Fevzi Pasha on 7 August 1917, who was under the command of the German general Erich von Falkenhayn‘s Yildirim Army Group (after the British forces of General Edmund Allenby captured Jerusalem in December 1917, Erich von Falkenhayn was replaced by Otto Liman von Sanders who became the new commander of the Yıldırım Army Group in early 1918.)[57] Atatürk did not get along well with General von Falkenhayn and, together with Miralay İsmet Bey, wrote a report to Grand Vizier Talaat Pasha regarding the grim situation and lack of adequate resources in the Palestinian front. However, Talaat Pasha ignored their observations and refused their suggestion to form a stronger defensive line to the north, in Ottoman Syria (in parts of the Beirut Vilayet, Damascus Vilayet, and Aleppo Vilayet), with Turks instead of Germans in command.[57] Following the rejection of his report, Atatürk resigned from the Seventh Army and returned to Constantinople.[57] There, he was assigned with the task of accompanying the crown prince (and future sultan) Mehmed Vahideddin during his train trip to Austria-Hungary and Germany.[57] While in Germany, Atatürk visited the German lines on the Western Front and concluded that the Central Powers would soon lose the war.[57] He did not hesitate to openly express this opinion to Kaiser Wilhelm II and his high-ranking generals in person.[57] During the return trip, he briefly stayed in Karlsbad and Vienna for medical treatment.[57]Atatürk in 1918, the Commander of the Yıldırım Army Group and an Honoraryaide-de-camp of the Sultan

When Mehmed VI became the new Sultan of the Ottoman Empire in July 1918, he called Atatürk to Constantinople, and after several meetings in the months July and August 1918, re-assigned him to the command of the Seventh Army in Palestine.[69] Atatürk arrived in Aleppo on 26 August 1918, then continued south to his headquarters in Nablus. The Seventh Army was holding the central sector of the front lines. On 19 September, at the beginning of the Battle of Megiddo, the Eighth Army was holding the coastal flank but fell apart and Liman Pasha ordered the Seventh Army to withdraw to the north in order to prevent the British from conducting a short envelopment to the Jordan River. The Seventh Army retired towards the Jordan River but was destroyed by British aerial bombardment during its retreat from Nablus on 21 September 1918.[70] Nevertheless, Atatürk managed to form a defence line to the north of Aleppo. According to Lord Kinross, Atatürk was the only Turkish general in the war who never suffered a defeat.[71]

The war ended with the Armistice of Mudros which was signed on 30 October 1918, and all German and Austro-Hungarian troops in the Ottoman Empire were granted ample time to withdraw. On 31 October, Atatürk was appointed to the command of the Yıldırım Army Group, replacing Liman von Sanders. Atatürk organized the distribution of weapons to the civilians in Antep in case of a defensive conflict against the invading Allies.[57]

Atatürk’s last active service in the Ottoman Army was organizing the return of the Ottoman troops left behind to the south of the defensive line. In early November 1918, the Yıldırım Army Group was officially dissolved, and Atatürk returned to an occupied Constantinople, the Ottoman capital, on 13 November 1918.[57] For a period of time, he worked at the headquarters of the Ministry of War (Harbiye Nezareti) in Constantinople and continued his activities in this city until 16 May 1919.[57] Along the established lines of the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, the Allies (British, Italian, French and Greek forces) occupied Anatolia. The occupation of Constantinople, followed by the occupation of İzmir (the two largest Ottoman cities at the time) sparked the establishment of the Turkish National Movement and the Turkish War of Independence.[72]

Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923)

Main article: Turkish War of IndependenceSee also: Military career of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk § War of IndependenceAtatürk (right) in Angora (Ankara) with İsmet Pasha (left)

On 30 April 1919, Fahri Yaver-i Hazret-i Şehriyari (“Honorary Aide-de-camp to His Majesty Sultan”) Mirliva Atatürk was assigned as the inspector of the Ninth Army Troops Inspectorate to reorganize what remained of the Ottoman military units and to improve internal security.[73] On 19 May 1919, he reached Samsun. His first goal was the establishment of an organized national movement against the occupying forces. In June 1919, he issued the Amasya Circular, declaring the independence of the country was in danger. He resigned from the Ottoman Army on 8 July, and the Ottoman government issued a warrant for his arrest. But Kâzım Karabekir and other military commanders active in Eastern Anatolia followed Atatürk’s lead and acknowledged him as their leader.[74]

On 4 September 1919, he assembled a congress in Sivas. Those who opposed the Allies in various provinces in Turkey issued a declaration named Misak-ı Millî (“National Pact”). Atatürk was appointed as the head of the executive committee of the Congress,[75] which gave him the legitimacy he needed for his future politics.[76][75] (see Sivas Congress)

The last election to the Ottoman parliament held in December 1919 gave a sweeping majority to candidates of the “Association for Defence of Rights for Anatolia and Roumelia” (Anadolu ve Rumeli Müdafaa-i Hukuk Cemiyeti), headed by Atatürk, who himself remained in Angora, now known as Ankara. The fourth (and last) term of the parliament opened in Constantinople on 12 January 1920. It was dissolved by British forces on 18 March 1920, shortly after it adopted the Misak-ı Millî (“National Pact”). Atatürk called for a national election to establish a new Turkish Parliament seated in Angora.[77] – the “Grand National Assembly” (GNA). On 23 April 1920, the GNA opened with Atatürk as the speaker; this act effectively created the situation of diarchy in the country.[78] In May 1920, the power struggle between the two governments led to a death sentence in absentia for Mustafa Kemal by the Turkish courts-martial.[79] Halide Edib (Adıvar) and Ali Fuat (Cebesoy) were also sentenced to death alongside Atatürk.[80]Prominent nationalists at the Sivas Congress, left to right: Muzaffer (Kılıç), Rauf (Orbay), Bekir Sami (Kunduh), Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk), Ruşen Eşref (Ünaydın), Cemil Cahit (Toydemir), Cevat Abbas (Gürer)

On 10 August 1920, the Ottoman Grand Vizier Damat Ferid Pasha signed the Treaty of Sèvres, finalizing plans for the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, including the regions that Turkish nationals viewed as their heartland. Atatürk insisted on the country’s complete independence and the safeguarding of interests of the Turkish majority on “Turkish soil”. He persuaded the GNA to gather a National Army. The GNA army faced the Caliphate army propped up by the Allied occupation forces and had the immediate task of fighting the Armenian forces in the Eastern Front and the Greek forces advancing eastward from Smyrna (today known as İzmir) that they had occupied in May 1919, on the Western Front.[81]

The GNA military successes against the Democratic Republic of Armenia in the autumn of 1920 and later against the Greeks were made possible by a steady supply of gold and armaments to the Kemalists from the Russian Bolshevik government from the autumn of 1920 onwards.[82]Atatürk inspects the Turkish troops on 18 June 1922

After a series of battles during the Greco-Turkish War, the Greek army advanced as far as the Sakarya River, just eighty kilometers west of the GNA. On 5 August 1921, Atatürk was promoted to commander in chief of the forces by the GNA.[83] The ensuing Battle of Sakarya was fought from 23 August–13 September 1921 and ended with the defeat of the Greeks. After this victory, Atatürk was given the rank of Mareşal and the title of Gazi by the Grand National Assembly on 19 September 1921. The Allies, ignoring the extent of Atatürk’s successes, hoped to impose a modified version of the Treaty of Sèvres as a peace settlement on Angora, but the proposal was rejected. In August 1922, Atatürk launched an all-out attack on the Greek lines at Afyonkarahisar in the Battle of Dumlupınar, and Turkish forces regained control of İzmir on 9 September 1922.[84] On 10 September 1922, Atatürk sent a telegram to the League of Nations stating that the Turkish population was so worked up that the Ankara Government would not be responsible for the ensuing massacres.[85]

Establishment of the Republic of Turkey

See also: Treaty of Lausanne (1923)A British cartoon of 1923 satirising Atatürk’s rule in Turkey

The Conference of Lausanne began on 21 November 1922. Turkey, represented by İsmet İnönü of the GNA, refused any proposal that would compromise Turkish sovereignty,[86] such as the control of Turkish finances, the Capitulations, the Straits and other issues. Although the conference paused on 4 February, it continued after 23 April mainly focusing on the economic issues.[68] On 24 July 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed by the Powers with the GNA, thus recognising the latter as the government of Turkey.

On 29 October 1923, the Republic of Turkey was proclaimed.[87] Since then, Republic Day has been celebrated as a national holiday on that date.[88]

Presidency

For conceptual analysis, see Kemalism and Atatürk’s Reforms.

With the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, efforts to modernise the country started. The new government analyzed the institutions and constitutions of Western states such as France, Sweden, Italy, and Switzerland and adapted them to the needs and characteristics of the Turkish nation. Highlighting the public’s lack of knowledge regarding Atatürk’s intentions, the public cheered: “We are returning to the days of the first caliphs.”[89] Atatürk placed Fevzi Çakmak, Kâzım Özalp, and İsmet İnönü in political positions where they could institute his reforms. He capitalized on his reputation as an efficient military leader and spent the following years, up until his death in 1938, instituting political, economic, and social reforms. In doing so, he transformed Turkish society from perceiving itself as a Muslim part of a vast Empire into a modern, democratic, and secular nation-state. This had a positive influence on human capital because from then on, what mattered at school was science and education; Islam was concentrated in mosques and religious places.[90]

Domestic policies

Atatürk at the opening ceremony of the Samsun–Çarşamba railroad (1928)

Atatürk’s basic tenet was the complete independence of the country.[91] He clarified his position:

“…by complete independence, we mean of course complete economic, financial, juridical, military, cultural independence and freedom in all matters. Being deprived of independence in any of these is equivalent to the nation and country being deprived of all its independence”.[92]

He led wide-ranging reforms in social, cultural, and economic aspects, establishing the new Republic’s backbone of legislative, judicial, and economic structures. Though he was later idealized by some as an originator of sweeping reforms, many of his reformist ideas were already common in Ottoman intellectual circles at the turn of the 20th century and were expressed more openly after the Young Turk Revolution.[93]

Atatürk created a banner to mark the changes between the old Ottoman and the new republican rule. Each change was symbolized as an arrow in this banner. This defining ideology of the Republic of Turkey is referred to as the “Six Arrows”, or Kemalism. Kemalism is based on Atatürk’s conception of realism and pragmatism.[94] The fundamentals of nationalism, populism, and etatism were all defined under the Six Arrows. These fundamentals were not new in world politics or, indeed, among the elite of Turkey. What made them unique was that these interrelated fundamentals were explicitly formulated for Turkey’s needs. A good example is the definition and application of secularism; the Kemalist secular state significantly differed from predominantly Christian states.

Emergence of the state, 1923–1924

Atatürk in 1923, with members of the Mevlevi Order, before its institutional expression became illegal and their dervish lodge was changed into the Mevlana Museum. The Mevlevi Order managed to transform itself into a non-political organization which still exists.

Atatürk’s private journal entries dated before the establishment of the republic in 1923 show that he believed in the importance of the sovereignty of the people. In forging the new republic, the Turkish revolutionaries turned their back on the perceived corruption and decadence of cosmopolitan Constantinople and its Ottoman heritage.[95] For instance, they made Ankara (as Angora has been known in English since 1930), the country’s new capital and reformed the Turkish postal service. Once a provincial town deep in Anatolia, the city was thus turned into the center of the independence movement. Atatürk wanted a “direct government by the Assembly”[96] and visualized a representative democracy, parliamentary sovereignty, where the National Parliament would be the ultimate source of power.[96]

In the following years, he altered his stance somewhat; the country needed an immense amount of reconstruction, and “direct government by the Assembly” could not survive in such an environment. The revolutionaries faced challenges from the supporters of the old Ottoman regime, and also from the supporters of newer ideologies such as communism and fascism. Atatürk saw the consequences of fascist and communist doctrines in the 1920s and 1930s and rejected both.[97] He prevented the spread into Turkey of the totalitarian party rule which held sway in the Soviet Union, Germany, and Italy.[98] Some perceived his opposition and silencing of these ideologies as a means of eliminating competition; others believed it was necessary to protect the young Turkish state from succumbing to the instability of new ideologies and competing factions.[99] Under Atatürk, the arrest process known as the Arrests of 1927 (1927 Tevkifatı) was launched, and a widespread arrest policy was put in place against the Communist Party of Turkey members. Communist political figures such as Hikmet Kıvılcımlı, Nâzım Hikmet, and Şefik Hüsnü were tried and sentenced to prison terms. Then, in 1937, a delegation headed by Atatürk decided to censor the writings of Kıvılcımlı as harmful communist propaganda.[100][101][102]In 1924, during his speech in Bursa

The heart of the new republic was the GNA, established during the Turkish War of Independence by Atatürk.[103] The elections were free and used an egalitarian electoral system that was based on a general ballot.[103] Deputies at the GNA served as the voice of Turkish society by expressing its political views and preferences. It had the right to select and control both the government and the Prime Minister. Initially, it also acted as a legislative power, controlling the executive branch and, if necessary, served as an organ of scrutiny under the Turkish Constitution of 1921.[103] The Turkish Constitution of 1924 set a loose separation of powers between the legislative and the executive organs of the state, whereas the separation of these two within the judiciary system was a strict one. Atatürk, then the President, occupied a dominant position in this political system.

The one-party regime was established de facto in 1925 after the adoption of the 1924 constitution. The only political party of the GNA was the “People’s Party”, founded by Atatürk on 9 September 1923. (But according to the party culture the foundation date was the opening day of Sivas Congress on 4 September 1919). On 10 November 1924, it was renamed Cumhuriyet Halk Fırkası or Republican People’s Party (the word fırka was replaced by the word parti in 1935).

Civic independence and the Caliphate, 1924–1925

Atatürk during the Republic Day celebrations on the second anniversary of the Turkish Republic, 29 October 1925.

The abolition of the caliphate and other cultural reforms were met with fierce opposition. The conservative elements were not appreciative, and they launched attacks on the Kemalist reformists.[104]

Abolition of the Caliphate was an important dimension in Atatürk’s drive to reform the political system and to promote national sovereignty. By the consensus of the Muslim majority in early centuries, the caliphate was the core political concept of Sunni Islam.[105] Abolishing the sultanate was easier because the survival of the Caliphate at the time satisfied the partisans of the sultanate. This produced a split system with the new republic on one side and an Islamic form of government with the Caliph on the other side, and Atatürk and İnönü worried that “it nourished the expectations that the sovereign would return under the guise of Caliph.”[106] Caliph Abdülmecid II was elected after the abolition of the sultanate (1922).

The caliph had his own personal treasury and also had a personal service that included military personnel; Atatürk said that there was no “religious” or “political” justification for this. He believed that Caliph Abdülmecid II was following in the steps of the sultans in domestic and foreign affairs: accepting of and responding to foreign representatives and reserve officers, and participating in official ceremonies and celebrations.[107] He wanted to integrate the powers of the caliphate into the powers of the GNA. His initial activities began on 1 January 1924, when[107] İnönü, Çakmak, and Özalp consented to the abolition of the caliphate. The caliph made a statement to the effect that he would not interfere with political affairs.[104] On 1 March 1924, at the Assembly, Atatürk said:

“The religion of Islam will be elevated if it will cease to be a political instrument, as had been the case in the past”.[108]

On 3 March 1924, the caliphate was officially abolished and its powers within Turkey were transferred to the GNA. Other Muslim nations debated the validity of Turkey’s unilateral abolition of the caliphate as they decided whether they should confirm the Turkish action or appoint a new caliph.[104] A “Caliphate Conference” was held in Cairo in May 1926 and a resolution was passed declaring the caliphate “a necessity in Islam”, but failed to implement this decision.[104]

Two other Islamic conferences were held in Mecca (1926) and Jerusalem (1931), but failed to reach a consensus.[104] Turkey did not accept the re-establishment of the caliphate and perceived it as an attack to its basic existence. Meanwhile, Atatürk and the reformists continued their own way.[109]

On 8 April 1924, sharia courts were abolished with the law “Mehakim-i Şer’iyenin İlgasına ve Mehakim Teşkilatına Ait Ahkamı Muaddil Kanun”.[110][111]

Educational reform

The removal of the caliphate was followed by an extensive effort to establish the separation of governmental and religious affairs. Education was the cornerstone in this effort. In 1923, there were three main educational groups of institutions. The most common institutions were medreses based on Arabic, the Qur’an, and memorization. The second type of institution was idadî and sultanî, the reformist schools of the Tanzimat era. The last group included colleges and minority schools in foreign languages that used the latest teaching models in educating pupils. The old medrese education was modernized.[112] Atatürk changed the classical Islamic education for a vigorously promoted reconstruction of educational institutions.[112] He linked educational reform to the liberation of the nation from dogma, which he believed was more important than the Turkish War of Independence. He declared:

“Today, our most important and most productive task is the national education [unification and modernization] affairs. We have to be successful in national education affairs and we shall be. The liberation of a nation is only achieved through this way.”[113]

In the summer of 1924, Atatürk invited American educational reformer John Dewey to Ankara to advise him on how to reform Turkish education.[112] His public education reforms aimed to prepare citizens for roles in public life through increasing public literacy. He wanted to institute compulsory primary education for both girls and boys; since then this effort has been an ongoing task for the republic. He pointed out that one of the main targets of education in Turkey had to be raising a generation nourished with what he called the “public culture”. The state schools established a common curriculum which became known as the “unification of education.”

Unification of education was put into force on 3 March 1924 by the Law on Unification of Education (No. 430). With the new law, education became inclusive, organized on a model of the civil community. In this new design, all schools submitted their curriculum to the “Ministry of National Education“, a government agency modeled after other countries’ ministries of education. Concurrently, the republic abolished the two ministries and made clergy subordinate to the department of religious affairs, one of the foundations of secularism in Turkey. The unification of education under one curriculum ended “clerics or clergy of the Ottoman Empire”, but was not the end of religious schools in Turkey; they were moved to higher education until later governments restored them to their former position in secondary after Atatürk’s death.Atatürk with his Panama hat just after the Kastamonu speech in 1925

Western attire

Beginning in the fall of 1925, Atatürk encouraged the Turks to wear modern European attire.[114] He was determined to force the abandonment of the sartorial traditions of the Middle East and finalize a series of dress reforms, which were originally started by Mahmud II.[114] The fez was established by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826 as part of the Ottoman Empire’s modernization effort. The Hat Law of 1925 introduced the use of Western-style hats instead of the fez. Atatürk first made the hat compulsory for civil servants.[114] The guidelines for the proper dressing of students and state employees were passed during his lifetime; many civil servants adopted the hat willingly. In 1925, Atatürk wore a Panama hat during a public appearance in Kastamonu, one of the most conservative towns in Anatolia, to explain that the hat was the headgear of civilized nations. The last part of reform on dress emphasized the need to wear modern Western suits with neckties as well as Fedora and Derby-style hats instead of antiquated religion-based clothing such as the veil and turban in the Law Relating to Prohibited Garments of 1934.

Even though he personally promoted modern dress for women, Atatürk never made specific reference to women’s clothing in the law, as he believed that women would adapt to the new clothing styles of their own free will. He was frequently photographed on public business with his wife Lâtife Uşaklıgil, who covered her head in accordance with Islamic tradition. He was also frequently photographed on public business with women wearing modern Western clothes. But it was Atatürk’s adopted daughters, Sabiha Gökçen and Afet İnan, who provided the real role model for the Turkish women of the future. He wrote: “The religious covering of women will not cause difficulty … This simple style [of headcovering] is not in conflict with the morals and manners of our society.”[115]

Religious insignia

On 30 August 1925, Atatürk’s view on religious insignia used outside places of worship was introduced in his Kastamonu speech. This speech also had another position. He said:

“In the face of knowledge, science, and of the whole extent of radiant civilization, I cannot accept the presence in Turkey’s civilized community of people primitive enough to seek material and spiritual benefits in the guidance of sheiks. The Turkish republic cannot be a country of sheiks, dervishes, and disciples. The best, the truest order is the order of civilization. To be a man it is enough to carry out the requirements of civilization. The leaders of dervish orders will understand the truth of my words, and will themselves close down their lodges [tekke] and admit that their disciplines have grown up”.[116][117]

On 2 September, the government issued a decree closing down all Sufi orders and the tekkes. Atatürk ordered their dervish lodges to be converted to museums, such as Mevlana Museum in Konya. The institutional expression of Sufism became illegal in Turkey; a politically neutral form of Sufism, functioning as social associations, was permitted to exist.[118]

Opposition to Atatürk in 1924–1927

Atatürk is greeted by marines in Büyükada (14 July 1927)

In 1924, while the “Issue of Mosul” was on the table, Sheikh Said began to organize the Sheikh Said Rebellion. Sheikh Said was a wealthy Kurdish tribal chief of a local Naqshbandi order in Diyarbakır. He emphasized the issue of religion; he not only opposed the abolition of the Caliphate, but also the adoption of civil codes based on Western models, the closure of religious orders, the ban on polygamy, and the new obligatory civil marriage. Sheikh stirred up his followers against the policies of the government, which he considered anti-Islamic. In an effort to restore Islamic law, Sheik’s forces moved through the countryside, seized government offices and marched on the important cities of Elazığ and Diyarbakır.[119] Members of the government saw the Sheikh Said Rebellion as an attempt at a counter-revolution. They urged immediate military action to prevent its spread. With the support of Mustafa Kemal, the acting prime minister Ali Fethi (Okyar) replaced with Ismet Inönü who on the 3 March 1925 ordered the invocation of the “Law for the Maintenance of Order” in order to deal with the rebellion. It gave the government exceptional powers and included the authority to shut down subversive groups.[120] The law was repealed in March 1927.[121]

There were also parliamentarians in the GNA who were not happy with these changes[who?]. So many members were denounced as opposition sympathizers at a private meeting of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) that Atatürk expressed his fear of being among the minority in his own party.[122] He decided not to purge this group.[122] After a censure motion gave the chance to have a breakaway group, Kâzım Karabekir, along with his friends, established such a group on 17 October 1924. The censure became a confidence vote at the CHP for Atatürk. On 8 November, the motion was rejected by 148 votes to 18, and 41 votes were absent.[122] The CHP held all but one seat in the parliament. After the majority of the CHP chose him,[122] Atatürk said, “the Turkish nation is firmly determined to advance fearlessly on the path of the republic, civilization and progress”.[122]

On 17 November 1924, the breakaway group established the Progressive Republican Party (PRP) with 29 deputies and the first multi-party system began. Some of Atatürk’s closest associates who had supported him in the early days of the War of Independence such as Rauf Bey (later Rauf Orbay), Refet Pasha, and Ali Fuat Pasha (later Ali Fuat Cebesoy) were among the members of the new party. The PRP’s economic program suggested liberalism, in contrast to the state socialism of the CHP, and its social program was based on conservatism in contrast to the modernism of the CHP. Leaders of the party strongly supported the Kemalist revolution in principle, but had different opinions on the cultural revolution and the principle of secularism.[123] The PRP was not against Atatürk’s main positions as declared in its program; they supported establishing secularism in the country and the civil law, or as stated, “the needs of the age” (article 3) and the uniform system of education (article 49).[124] These principles were set by the leaders at the onset. The only legal opposition became a home for all kinds of differing views.

During 1926, a plot to assassinate Atatürk was uncovered in Smyrna (İzmir). It originated with a former deputy who had opposed the abolition of the Caliphate. What originally was an inquiry into the planners shifted to a sweeping investigation. Ostensibly, its aims were to uncover subversive activities, but in truth, the investigation was used to undermine those disagreeing with Atatürk’s cultural revolution. The investigation brought a number of political activists before the tribunal, including Karabekir, the leader of the PRP. A number of surviving leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress, including Mehmet Cavid, Ahmed Şükrü, and İsmail Canbulat, were found guilty of treason and hanged.[125] Because the investigation found a link between the members of the PRP and the Sheikh Said Rebellion, the PRP was dissolved following the outcomes of the trial. The pattern of organized opposition was broken; this action was to be the only broad political purge during Atatürk’s presidency. Atatürk’s statement, “My mortal body will turn into dust, but the Republic of Turkey will last forever,” was regarded as a will after the assassination attempt.[126]

Modernization efforts, 1926–1930

Atatürk at the 1927 opening of the State Art and Sculpture Museum

In the years following 1926, Atatürk introduced a radical departure from previous reformations established by the Ottoman Empire.[127] For the first time in history, Islamic law was separated from secular law and restricted to matters of religion.[127] He stated:

“We must liberate our concepts of justice, our laws and our legal institutions from the bonds which, even though they are incompatible with the needs of our century, still hold a tight grip on us”.[128]

Atatürk at the library of the Çankaya Presidential Residence in Ankara, on 16 July 1929

On 1 March 1926, the Turkish penal code, modelled after the Italian penal code, was passed. On 4 October 1926, Islamic courts were closed. Establishing the civic law needed time, so Atatürk delayed the inclusion of the principle of laïcité (the constitutional principle of secularism in France) until 5 February 1937.Atatürk attending a class at the Law School of the Istanbul House of Multiple Sciences in 1930

In keeping with the Islamic practice of sex segregation, Ottoman practice discouraged social interaction between men and women. Atatürk began developing social reforms to address this issue very early, as was evident in his personal journal. He and his staff discussed issues such as abolishing the veiling of women and integrating women into the outside world. His plans to surmount the task were written in his journal in November 1915:

“The social change can come by (1) educating capable mothers who are knowledgeable about life; (2) giving freedom to women; (3) a man can change his morals, thoughts, and feelings by leading a common life with a woman; as there is an inborn tendency towards the attraction of mutual affection”.[129]

This documentary film is about Atatürk and the modernization of the Turkish Republic.

Atatürk needed a new civil code to establish his second major step of giving freedom to women. The first part was the education of girls, a feat established with the unification of education. On 4 October 1926, the new Turkish civil code, modelled after the Swiss Civil Code, was passed. Under the new code, women gained equality with men in such matters as inheritance and divorce, since Atatürk did not consider gender a factor in social organization. According to his view, society marched towards its goal with men and women united. He believed that it was scientifically impossible for Turkey to achieve progress and become civilized if Ottoman gender separation persisted.[130] During a meeting he declaimed:

“To the women: Win for us the battle of education and you will do yet more for your country than we have been able to do. It is to you that I appeal.

To the men: If henceforward the women do not share in the social life of the nation, we shall never attain to our full development. We shall remain irremediably backward, incapable of treating on equal terms with the civilizations of the West”.[131]In 1927, the State Art and Sculpture Museum (Ankara Resim ve Heykel Müzesi) opened its doors. The museum highlighted sculpture, which was rarely practised in Turkey due to the Islamic tradition of avoiding idolatry. Atatürk believed that “culture is the foundation of the Turkish Republic,”[132] and described modern Turkey’s ideological thrust as “a creation of patriotism blended with a lofty humanist ideal.” He included both his own nation’s creative legacy and what he saw as the admirable values of global civilization. The pre-Islamic culture of the Turks became the subject of extensive research, and particular emphasis was placed on the widespread Turkish culture before the Seljuk and Ottoman civilizations. He instigated study of Anatolian civilizations – Phrygians, Lydians, Sumerians, and Hittites. To attract public attention to past cultures, he personally named the banks “Sümerbank” (1932) after the Sumerians and “Etibank” (1935) after the Hittites. He also stressed the folk arts of the countryside as a wellspring of Turkish creativity.

At the time, the republic used the Ottoman Turkish language written in the Arabic script with Arabic and Persian loan vocabulary.[112] However, as little as 10% of the population was literate. Furthermore, the American reformer John Dewey, invited by Atatürk to assist in educational reform, found that learning how to read and write Turkish in the traditional Arabic script took roughly three years.[112] In the spring of 1928, Atatürk met in Ankara with several linguists and professors from all over Turkey to unveil his plan to implement a new alphabet for the written Turkish language, based on a modified Latin alphabet. The new Turkish alphabet would serve as a replacement for the old Arabic script and a solution to the literacy problem, since the new alphabet did not retain the complexities of the Arabic script and could be learned within a few months.[21] When Atatürk asked the language experts how long it would take to implement the new alphabet into the Turkish language, most of the professors and linguists said between three and five years. Atatürk was said to have scoffed and openly stated, “We shall do it in three to five months”.[133]Atatürk introducing the new Turkish alphabet to the people of Kayseri on 20 September 1928

Over the next several months, Atatürk pressed for the introduction of the new Turkish alphabet and made public announcements of the upcoming overhaul. The creation of the alphabet was undertaken by the Language Commission (Dil Encümeni) with the initiative of Atatürk.[112] On 1 November 1928, he introduced the new Turkish alphabet and abolished the use of the Arabic script. The first Turkish newspaper using the new alphabet was published on 15 December 1928. Atatürk himself travelled the countryside in order to teach citizens the new alphabet. After vigorous campaigns, the literacy rate more than doubled from 10.6% in 1927 to 22.4% in 1940.[134] To supplement the literacy reform, a number of congresses were organized on scientific issues, education, history, economics, arts and language.[135] Libraries were systematically developed, and mobile libraries and book transport systems were set up to serve remote districts.[136] Literacy reform was also supported by strengthening the private publishing sector with a new law on copyrights.

Atatürk promoted modern teaching methods at the primary education level, and Dewey proved integral to the effort.[112] Dewey presented a paradigmatic set of recommendations designed for developing societies moving towards modernity in his “Report and Recommendation for the Turkish educational system”.[112] He was interested in adult education with the goal of forming a skill base in the country. Turkish women were taught not only child care, dress-making, and household management but also skills necessary for joining the economy outside the home. Atatürk’s unified education program became a state-supervised system, which was designed to create a skill base for the social and economic progress of the country by educating responsible citizens as well as useful and appreciated members of society.[137][112] In addition, Turkish education became an integrative system, aimed to alleviate poverty and used female education to establish gender equality. Atatürk himself put special emphasis on the education of girls and supported coeducation, introducing it at university level in 1923–24 and establishing it as the norm throughout the educational system by 1927.[138] Atatürk’s reforms on education made it significantly more accessible: between 1923 and 1938, the number of students attending primary schools increased by 224% (from 342,000 to 765,000), the number of students attending middle schools increased by 12.5 times (from around 6,000 to 74,000), and the number of students attending high schools increased by almost 17 times (from 1,200 to 21,000).[139]In 1930, leaving the parliament after the 7th-year celebration meeting.

Atatürk generated media attention to propagate modern education during this period. He instigated official education meetings called “Science Boards” and “Education Summits” to discuss the quality of education, training issues, and certain basic educational principles. He said, “our [schools’ curriculum] should aim to provide opportunities for all pupils to learn and to achieve.” He was personally engaged with the development of two textbooks. The first one, Vatandaş İçin Medeni Bilgiler (Civic knowledge for the citizens, 1930), introduced the science of comparative government and explained the means of administering public trust by explaining the rules of governance as applied to the new state institutions.[140] The second, Geometri (Geometry, 1937), was a text for high schools and introduced many of the terms currently used in Turkey to describe geometry.[141]

Opposition to Atatürk in 1930–1931

On 11 August 1930, Atatürk decided to try a multiparty movement once again and asked Fethi Okyar to establish a new party. Atatürk insisted on the protection of secular reforms. The brand-new Liberal Republican Party succeeded all around the country. However, without the establishment of a real political spectrum, the party became the center to opposition of Atatürk’s reforms, particularly in regard to the role of religion in public life.

On 23 December 1930, a chain of violent incidents occurred, instigated by the rebellion of Islamic fundamentalists in Menemen, a small town in the Aegean Region. The Menemen Incident came to be considered a serious threat against secular reforms.Atatürk with the Liberal Republican Party leader Fethi Okyar and his daughter in Yalova, on 13 August 1930

In November 1930, Ali Fethi Okyar dissolved his own party. A more lasting multi-party period of the Republic of Turkey began in 1945. In 1950, the CHP ceded the majority position to the Democratic Party. This came amidst arguments that Atatürk’s single-party rule did not promote direct democracy. The reason experiments with pluralism failed during this period was that not all groups in the country had agreed to a minimal consensus regarding shared values (mainly secularism) and shared rules for conflict resolution. In response to such criticisms, Atatürk’s biographer Andrew Mango writes: “between the two wars, democracy could not be sustained in many relatively richer and better-educated societies. Atatürk’s enlightened authoritarianism left a reasonable space for free private lives. More could not have been expected in his lifetime.”[142] Even though, at times, he did not appear to be a democrat in his actions, Atatürk always supported the idea of building a civil society: a system of voluntary civic and social organizations and institutions as opposed to the force-backed structures of the state. In one of his many speeches about the importance of democracy, Atatürk said in 1933:

“Republic means the democratic administration of the state. We founded the Republic, reaching its tenth year. It should enforce all the requirements of democracy as the time comes”.[143]

Modernization efforts, 1931–1938

In 1931, during the establishment ceremony of the Turkish History Institution. Atatürk is standing with Afet İnan (on his left) and Yusuf Akçura (first from the left).Atatürk at the opening of the Türkkuşu flight school in Etimesgut on 3 May 1935

In 1931, Atatürk established the Turkish Language Association (Türk Dil Kurumu) for conducting research works in the Turkish language. The Turkish Historical Society (Türk Tarih Kurumu) was established in 1931, and began maintaining archives in 1932 for conducting research works on the history of Turkey.[144] On 1 January 1928, he established the Turkish Education Association,[144] which supported intelligent and hard-working children in financial need, as well as material and scientific contributions to the educational life. In 1933, Atatürk ordered the reorganization of Istanbul University into a modern institution and later established Ankara University in the capital city.[145]

Atatürk dealt with the translation of scientific terminology into Turkish.[146] He wanted the Turkish language reform to be methodologically based. Any attempt to “cleanse” the Turkish language of foreign influence without modelling the integral structure of the language was inherently wrong to him. He personally oversaw the development of the Sun Language Theory (Güneş Dil Teorisi), which was a linguistic theory which proposed that all human languages were descendants of one Central Asian primal language. His ideas could be traced to the work by the French scientist Hilaire de Barenton titled L’Origine des Langues, des Religions et des Peuples, which postulates that all languages originated from hieroglyphs and cuneiform used by Sumerians,[147] and the paper by Austrian linguist Dr. Hermann F. Kvergić of Vienna titled “La psychologie de quelques éléments des langues Turques” (“the psychology of some elements of the Turkic Languages“).[148] Atatürk formally introduced the Sun Language Theory into Turkish political and educational circles in 1935, although he did later correct the more extremist practices.[146]

Saffet Arıkan, a politician who was the head of the Turkish Language Association, said “Ulu Önderimiz Ata Türk Mustafa Kemal” (“Our Great Leader Ata Türk Mustafa Kemal”) in the opening speech of the 2nd Language Day on 26 September 1934. Later, the surname “Atatürk” (“father of the Turks”) was accepted as the surname of Mustafa Kemal after the adoption of the Surname Law in 1934.[149]

Beginning in 1932, several hundred “People’s Houses” (Halkevleri) and “People’s Rooms” (Halkodaları) across the country allowed greater access to a wide variety of artistic activities, sports, and other cultural events. Atatürk supported and encouraged the visual and the plastic arts, which had been suppressed by Ottoman leaders, who regarded depiction of the human form as idolatry. Many museums opened, architecture began to follow modern trends, and classical Western music, opera, ballet, and theatre took greater hold in the country. Book and magazine publications increased as well, and the film industry began to grow.

Almost all Qur’ans in Turkey before the 1930s were printed in Old Arabic. However, in 1924, three Turkish translations of the Qur’an were published in Istanbul, and several renderings of the Qur’an in the Turkish language were read in front of the public, creating significant controversy.[150] These Turkish Qur’ans were fiercely opposed by members of the religious community, and the incident impelled many leading Muslim modernists to call upon the Turkish Parliament to sponsor a Qur’an translation of suitable quality.[151] With the support of Atatürk, the Parliament approved the project and the Directorate of Religious Affairs appointed Mehmet Akif (Ersoy) to compose a Qur’an translation, and the Islamic scholar Elmalılı Hamdi Yazır to author a Turkish language Qur’anic commentary (tafsir) titled Hak Dini Kur’an Dili (The Qur’an: the Tongue of the Religion of Truth).[152] However, it was only in 1935 that the version of Yazır’s work read in public found its way to print.[153] In 1932, Atatürk justified the translation of the Qur’an by stating how he wanted to “teach religion in Turkish to Turkish people who had been practising Islam without understanding it for centuries.” Atatürk believed that the understanding of religion and its texts was too important to be left to a small group of people. Thus, his objective was to make the Qur’an accessible to a broader demographic by translating it into modern languages.[154]

In 1934, Atatürk commissioned the first Turkish operatic work, Özsoy. The opera, staged at the People’s House in Ankara, was composed by Adnan Saygun and performed by soprano Semiha Berksoy.[155]Eighteen female MPs joined the Turkish Parliament with the 1935 general elections.

On 5 December 1934, Turkey moved to grant full political rights to women. The equal rights of women in marriage had already been established in the earlier Turkish civil code.[156] The role of women in Atatürk’s cultural reforms was expressed in the civic book prepared under his supervision.[157] In it, he stated:

“There is no logical explanation for the political disenfranchisement of women. Any hesitation and negative mentality on this subject is nothing more than a fading social phenomenon of the past. …Women must have the right to vote and to be elected; because democracy dictates that, because there are interests that women must defend, and because there are social duties that women must perform”.[158]

The 1935 general elections yielded 18 female MPs out of a total of 395 representatives, compared to nine out of 615 members in the British House of Commons and six out of 435 in the US House of Representatives inaugurated that year.[159]

Unification and nationalisation efforts

When the modern Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, nationalism and secularism were two of the founding principles.[160] Atatürk aimed to create a nation state (ulus devlet) from the Turkish remnants of the Ottoman Empire. Kemalism defines the “Turkish People” as “those who protect and promote the moral, spiritual, cultural and humanistic values of the Turkish Nation.”[161] One of the goals of the establishment of the new Turkish state was to ensure “the domination of Turkish ethnic identity in every aspect of social life from the language that people speak in the streets to the language to be taught at schools, from the education to the industrial life, from the trade to the cadres of state officials, from the civil law to the settlement of citizens to particular regions.”[162] The process of unification through Turkification continued and was fostered under Atatürk’s government with such policies as Citizen speak Turkish! (Vatandaş Türkçe konuş!), an initiative created in the 1930s by law students but sponsored by the government. This campaign aimed to put pressure on non-Turkish speakers to speak Turkish in public.[15][163][13][12][164][165][166] However, the campaign went beyond the measures of a mere policy of speaking Turkish to an outright prevention of any other language.[15][163][167][168][169]

Another example of nationalisation was the Surname Law, which obligated the Turkish people to adopt fixed, hereditary surnames and forbade names that contained connotations of foreign cultures, nations, tribes, and religions.[13][166][170][171][172] As a result, many ethnic Armenians, Greeks, and Kurds changed their surnames.[171] Non-Turkish surnames ending with “yan, of, ef, viç, is, dis, poulos, aki, zade, shvili, madumu, veled, bin” could not be registered and were replaced by “-oğlu.”[173] Furthermore, the geographical name changes initiative by the Turkish government replaced non-Turkish geographical and topographic names within the Turkish Republic with Turkish names.[174][175][14][176][177][178] The main proponent of the initiative had been a Turkish homogenization social-engineering campaign which aimed to assimilate geographical or topographical names that were deemed foreign and divisive against Turkish unity. The names that were considered foreign were usually of Armenian, Greek, Laz, Bulgarian, Kurdish, Assyrian, or Arabic origin.[174][14][177][178][179]

The 1934 Resettlement Law was a policy adopted by the Turkish government which set forth the basic principles of immigration.[180] The law, however, is regarded by some as a policy of assimilation of non-Turkish minorities through a forced and collective resettlement.[181]

Foreign policies

Atatürk with KingAmānullāh Khān of Afghanistan in Ankara, 1928. King Amānullāh attempted to emulate many of Atatürk’s reforms in Afghanistan, but was overthrown.

Atatürk’s foreign policy followed his motto “Peace at home, peace in the world“,[182] a perception of peace linked to his project of civilization and modernization.[183] The outcomes of Atatürk’s policies depended on the power of the parliamentary sovereignty established by the Republic.[184] The Turkish War of Independence was the last time Atatürk used his military might in dealing with other countries. Foreign issues were resolved by peaceful methods during his presidency.

Issue of Mosul

The Issue of Mosul, a dispute with the United Kingdom over control of Mosul Province, was one of the first foreign affairs-related controversies of the new Republic. During the Mesopotamian campaign, Lieutenant General William Marshall followed the British War Office’s instruction that “every effort was to be made to score as heavily as possible on the Tigris before the whistle blew”, capturing Mosul three days after the signature of the Armistice of Mudros (30 October 1918).[185] In 1920, the Misak-ı Milli, which consolidated the “Turkish lands”, declared that Mosul Province was a part of the historic Turkish heartland. The British were in a precarious situation with the Issue of Mosul and were adopting almost equally desperate measures to protect their interests. For example, the Iraqi revolt against the British was suppressed by the RAF Iraq Command during the summer of 1920. From the British perspective, if Atatürk stabilized Turkey, he would then turn his attention to Mosul and penetrate Mesopotamia, where the native population would likely join his cause. Such an event would result in an insurgent and hostile Muslim nation in close proximity to British territory in India.Atatürk with King Faisal I of Iraq in Ankara, 1931

In 1923, Atatürk tried to persuade the GNA that accepting the arbitration of the League of Nations at the Treaty of Lausanne did not signify relinquishing Mosul, but rather waiting for a time when Turkey might be stronger. Nevertheless, the artificially drawn border had an unsettling effect on the population on both sides. Later, it was claimed that Turkey began where the oil ends, as the border was drawn by the British geophysicists based on locations of oil reserves. Atatürk did not want this separation.[186] To address Atatürk’s concerns, the British Foreign Secretary George Curzon attempted to disclaim the existence of oil in the Mosul area. On 23 January 1923, Curzon argued that the existence of oil was no more than hypothetical.[185] However, according to the biographer Armstrong, “England wanted oil. Mosul and Kurds were the key.”[7]

While three inspectors from the League of Nations Committee were sent to the region to oversee the situation in 1924, the Sheikh Said rebellion (1924–1927) set out to establish a new government positioned to cut Turkey’s link to Mesopotamia. The relationship between the rebels and Britain was investigated. In fact, British assistance was sought after the rebels decided that the rebellion could not stand by itself.[187]

In 1925, the League of Nations formed a three-member committee to study the case while the Sheikh Said Rebellion was on the rise. Partly because of the continuing uncertainties along the northern frontier (present-day northern Iraq), the committee recommended that the region should be connected to Iraq with the condition that the UK would hold the British Mandate of Mesopotamia. By the end of March 1925, the necessary troop movements were completed, and the whole area of the Sheikh Said rebellion was encircled.[188] As a result of these manoeuvres, the revolt was put down. Britain, Iraq, and Atatürk made a treaty on 5 June 1926, which mostly followed the decisions of the League Council. The agreement left a large section of the Kurdish population and the Iraqi Turkmen on the non-Turkish side of the border.[189][190]

Relations with the Russian SFSR/Soviet Union

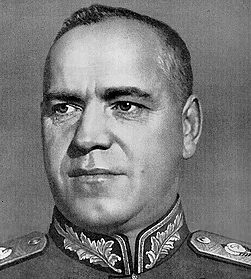

See also: Russia–Turkey relations § Turkey and the Soviet UnionDuring a reception at the USSR Embassy in Ankara, on 7 November 1927Exchanges on the concept of a Balkan Federation during the visit of Voroshilov, a vision of Atatürk’s which was never achieved

In his 26 April 1920 message to Vladimir Lenin, the Bolshevik leader and head of the Russian SFSR‘s government Atatürk promised to coordinate his military operations with the Bolsheviks’ “fight against imperialist governments” and requested 5 million lira in gold as well as armaments “as first aid” to his forces.[191] In 1920 alone, the Lenin government supplied the Kemalists with 6,000 rifles, over 5 million rifle cartridges, 17,600 projectiles as well as 200.6 kg of gold bullion. In the subsequent 2 years, the amount of aid increased.[192]

In March 1921, the GNA representatives in Moscow signed the Treaty of Moscow (“Friendship and Brotherhood” Treaty) with Soviet Russia, which was a major diplomatic breakthrough for the Kemalists. The Treaty of Moscow, followed by the identical Treaty of Kars in October the same year, gave Turkey a favourable settlement of its north-eastern frontier at the expense of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic, then nominally an independent state.

Relations between the two countries were friendly but were based on the fact that they were against a common enemy: Britain and the West.[193] In 1920, Atatürk toyed with the idea of using a state-controlled Turkish Communist Party to forestall the perceived spread of communist ideas in the country and gain access to the Comintern‘s financing.

Despite his relations with the Soviet Union, Atatürk was not willing to commit Turkey to communism. “Friendship with Russia,” he said, “is not to adopt their ideology of communism for Turkey.”[193] Moreover, Atatürk declared, “Communism is a social issue. Social conditions, religion, and national traditions of our country confirm the opinion that Russian Communism is not applicable in Turkey.”[194] And in a speech on 1 November 1924, he said, “Our amicable relations with our old friend the Soviet Russian Republic are developing and progressing every day. As in past our Republican Government regards genuine and extensive good relations with Soviet Russia as the keystone of our foreign policy.”[193]

After the Turks withdrew their delegation from Geneva on 16 December 1925, they left the League of Nations Council to grant a mandate for the Mosul region to Britain without their consent. Atatürk countered[195] by concluding a non-aggression pact with the USSR on 17 December.[196] In 1935, the pact was prolonged for another 10 years.[197]

In 1933, the Soviet Defence Minister Kliment Voroshilov visited Turkey and attended the tenth year celebrations of the Republic.[198] Atatürk explained his position regarding the realization of his plan for a Balkan Federation economically uniting Turkey, Greece, Romania, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria.[198]

During the second half of the 1930s, Atatürk tried to establish a closer relationship with Britain and other major Western powers, which caused displeasure on the part of the Soviets. The second edition of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (Volume 20, 1953) was unequivocally critical of Atatürk’s policies in the last years of his rule, calling his domestic policies “anti-popular” and his foreign course as aimed at rapprochement with the “imperialist powers.”[199]

Turkish-Greek alliance

Atatürk (center) hosting the Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos (at the left) in Ankara, October 1930

The post-war leader of Greece, Eleftherios Venizelos, was also determined to establish normal relations between his country and Turkey. The war had devastated Western Anatolia, and the financial burden of Ottoman Muslim refugees from Greece blocked rapprochement. Venizelos moved forward with an agreement with Turkey, despite accusations of conceding too much on the issues of naval armaments and the properties of Ottoman Greeks from Turkey.[200] In spite of Turkish animosity against the Greeks, Atatürk resisted the pressures of historic enmities and was sensitive towards past tensions; at one point, he ordered the removal of a painting showing a Turkish soldier plunging his bayonet into a Greek soldier by stating, “What a revolting scene!”[201]

Greece renounced all its claims over Turkish territory, and the two sides concluded an agreement on 30 April 1930. On 25 October, Venizelos visited Turkey and signed a treaty of friendship.[202] Venizelos even forwarded Atatürk’s name for the 1934 Nobel Peace Prize.[203] Even after Venizelos’ fall from power, Greco-Turkish relations remained cordial. Indeed, Venizelos’ successor Panagis Tsaldaris came to visit Atatürk in September 1933 and signed a more comprehensive agreement called the Entente Cordiale between Greece and Turkey, which was a stepping stone for the Balkan Pact.

Greek Premier Ioannis Metaxas once stated, with regard to Atatürk, that “…Greece, which has the highest estimation of the renowned leader, heroic soldier, and enlightened creator of Turkey. We will never forget that President Atatürk was the true founder of the Turkish-Greek alliance based on a framework of common ideals and peaceful cooperation. He developed ties of friendship between the two nations which it would be unthinkable to dissolve. Greece will guard its fervent memories of this great man, who determined an unalterable future path for the noble Turkish nation.”[204]

Neighbours to the east

Atatürk (right) with Reza ShahPahlavi (left) of Iran, during the Shah‘s visit to Turkey

From 1919, Afghanistan was in the midst of a reformation period under Amanullah Khan. Afghan Foreign Minister Mahmud Tarzi was a follower of Atatürk’s domestic policy. Tarzi encouraged Amanullah Khan in social and political reform but urged that reforms should built on a strong government. During the late 1920s, Anglo-Afghan relations soured over British fears of an Afghan-Soviet friendship. On 20 May 1928, Anglo-Afghan politics gained a positive perspective, when Amanullah Khan and his wife, Queen Soraya Tarzi, were received by Atatürk in Istanbul.[205] This meeting was followed by a Turkey-Afghanistan Friendship and Cooperation pact on 22 May 1928. Atatürk supported Afghanistan’s integration into international organizations. In 1934, Afghanistan’s relations with the international community improved significantly when it joined the League of Nations.[206] Mahmud Tarzi received Atatürk’s personal support until he died on 22 November 1933 in Istanbul.

Atatürk and Reza Shah, leader of Iran, had a common approach regarding British imperialism and its influence in their countries, resulting in a slow but continuous rapprochement between Ankara and Tehran. Both governments sent diplomatic missions and messages of friendship to each other during the Turkish War of Independence.[207] The policy of the Ankara government in this period was to give moral support in order to reassure Iranian independence and territorial integrity.[208] The relations between the two countries were strained after the abolishment of the Caliphate. Iran’s Shi’a clergy did not accept Atatürk’s stance, and Iranian religious power centres perceived the real motive behind Atatürk’s reforms was to undermine the power of the clergy.[208] By the mid-1930s, Reza Shah’s efforts had upset the clergy throughout Iran, thus widening the gap between religion and government.[209] As Russia and Great Britain strengthened their holds in the Middle East, Atatürk feared the occupation and dismemberment of Iran as a multi-ethnic society by these European powers.[208] Like Atatürk, Reza Shah wanted to secure Iran’s borders, and in 1934, the Shah visited Atatürk.

In 1935, the draft of what would become the Treaty of Saadabad was paragraphed in Geneva, but its signing was delayed due to the border dispute between Iran and Iraq. On 8 July 1937, Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan signed the Saadabad Pact at Tehran. The signatories agreed to preserve their common frontiers, to consult together in all matters of common interest, and to commit no aggression against one another’s territory. The treaty united the Afghan King Zahir Shah‘s call for greater Oriental-Middle Eastern cooperation, Reza Shah’s goal in securing relations with Turkey that would help free Iran from Soviet and British influence, and Atatürk’s foreign policy of ensuring stability in the region. The treaty’s immediate outcome, however, was deterring Italian leader Mussolini from interfering in the Middle East.[210]

Turkish Straits

Atatürk observes the Turkish troops during the military exercise on 28 May 1936

On 24 July 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne included the Lausanne Straits Agreement. The Lausanne Straits Agreement stated that the Dardanelles should remain open to all commercial vessels: seizure of foreign military vessels was subject to certain limitations during peacetime, and, even as a neutral state, Turkey could not limit any military passage during wartime. The Lausanne Straits Agreement stated that the waterway was to be demilitarised and its management left to the Straits Commission. The demilitarised zone heavily restricted Turkey’s domination and sovereignty over the Straits, and the defence of Istanbul was impossible without sovereignty over the water that passed through it.