-

Frank Abagnale

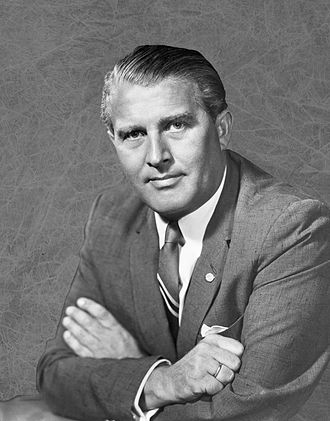

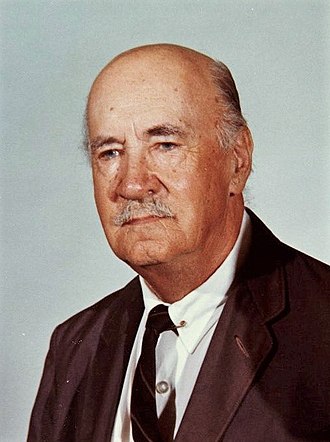

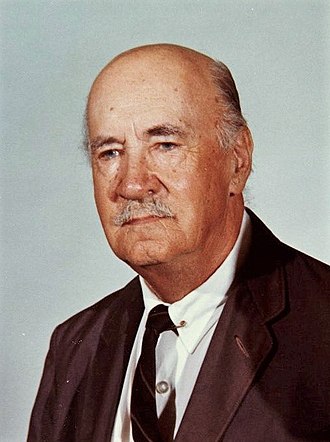

Frank William Abagnale Jr. (/ˈæbəɡneɪl/; born April 27, 1948) is an American author and convicted felon. He gained notoriety in the late 1970s with biographical claims that included working as an assistant state attorney general in Louisiana, a hospital physician in Georgia, a professor in Utah, and a Pan American World Airways pilot who logged over two million air miles.[1] According to Abagnale, he began to con people and pass bad checks when he was 15 years old. During his teens and early twenties he was arrested multiple times and was convicted and imprisoned in the United States and Europe. In 1980, Abagnale co-wrote a book on his life, Catch Me If You Can, that inspired the film of the same name directed by Steven Spielberg, in which Abagnale was portrayed by actor Leonardo DiCaprio. He has also written four other books. Abagnale runs Abagnale and Associates, a consultancy firm.[2]

The veracity of most of Abagnale’s claims has been questioned and in many cases outright refuted.[3][4][5] In 2002, Abagnale admitted on his website that some facts had been over-dramatized or exaggerated, though he was not specific about what was exaggerated or omitted about his life.[6] In 2020, journalist Alan C. Logan provided documentary evidence that the majority of Abagnale’s claims had been at best wildly exaggerated and at worst completely invented.[7][8][9]

Contents

- 1Early life

- 2Europe

- 3United States

- 4Veracity of claims

- 5Personal life

- 6Books

- 7See also

- 8References

- 9External links

Early life[edit source]

External video  Catch Me If You Can: Frank Abagnale’s Story, Frank Abagnale, 1:02:27, WGBH Educational Foundation[10]

Catch Me If You Can: Frank Abagnale’s Story, Frank Abagnale, 1:02:27, WGBH Educational Foundation[10]Frank William Abagnale Jr. was born in the Bronx, New York City, on April 27, 1948, to a French-Algerian mother and an Italian-American father.[11][12] He spent his early life in Bronxville, New York. His parents separated when he was 12 and divorced when he was 15 years old.[7] After the divorce, Abagnale moved with his father, and his new stepmother, to Mount Vernon, New York.[7]

According to Abagnale, his first victim was his father, who gave Abagnale a gasoline credit card and a truck and was ultimately liable for a bill amounting to $3,400. Abagnale was only 15 at the time.[13][14] In his autobiography, Abagnale says, because of this crime, he was sent to a reform school in Westchester County, New York (fitting the description of the Lincolndale Agricultural School) run by Catholic Charities USA.[13]

In December 1964, he enlisted in the United States Navy at the age of 16. He was discharged after less than three months and was arrested for forgery shortly thereafter.[15][16]

In 1965, the Federal Bureau of Investigation arrested Abagnale in Eureka, California for car theft after he stole a Ford Mustang from one of his father’s neighbors. Abagnale was pictured in the local newspaper, seated in a car, being questioned by special agent Richard Miller of the FBI.[17] He had financed his cross-country trip from New York to California with blank checks stolen from a family business located on the Bronx River Parkway.[15][16] Abagnale was also charged with impersonating a US customs official, although this charge was dropped. On June 2, 1965, this stolen car case was transferred to the Southern District of New York.[7]

Airline pilot[edit source]

After being released into the custody of his father to face the stolen car charges, 17-year-old Abagnale decided to impersonate a pilot. He obtained a uniform at a Manhattan uniform company, but was arrested in Tuckahoe, New York days later.[15][16] Abagnale was sentenced to three years at the Great Meadow Prison in Comstock, New York. After serving only two years of his sentence, he was released into the custody of his mother. However, he broke the terms of his parole with a stolen car conviction in Boston, Massachusetts, and was returned to Great Meadow for one year.[7]

After his release on December 24, 1968, he disguised himself as a TWA pilot and moved to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he talked his way into the house of a local music teacher, the father of a Delta Air Lines stewardess he had met in New York. He was arrested on February 14, 1969, initially on vagrancy charges. Upon his arrest he was found to have illegally driven his Florida rental car out of state and to possess falsified airline employee identification.[18] The following day detectives determined that Abagnale had stolen blank checks from his host family and a local business in Baton Rouge, and he was subsequently charged with theft and forgery.[19][20] Unable to make bail, he was convicted on June 2, 1969, and was sentenced to 12 years of supervised probation, but he soon fled Louisiana for Europe.[7][21]

Europe[edit source]

Two weeks after the Louisiana bench warrant was issued, Abagnale was arrested in Montpellier, France, in September 1969. He had stolen an automobile and defrauded two local families in Klippan, Sweden. He was sentenced to four months for theft in France, but only served three months in Perpignan‘s prison.[22]

He was then extradited to Sweden where he was convicted of gross fraud by forgery. He served two months in a Malmö prison and was banned from returning to Sweden for eight years and required to recompense his Swedish victims (which, they say, he never did[7]). Abagnale was deported back to the United States in June 1970 when his appeal failed.[7]

United States[edit source]

After returning to the United States, 22-year-old Abagnale dressed in a pilot’s uniform and travelled around college campuses, passing bad checks and claiming he was there to recruit stewardesses for Pan Am. At the University of Arizona, he stated that he was a pilot and a doctor, and according to Paul Holsen, a student at the time, Abagnale conducted physical examinations on several female college students who wanted to be part of flight crews.[23] None of the women were ever enrolled in Abagnale’s fictional program.[24]

After Abagnale cashed a personal check dressed up as a Pan Am paycheck, on July 30, 1970, in Durham, North Carolina, he again came to the attention of the FBI. He was arrested in Cobb County, Georgia, 3 months later, on November 2, 1970, after cashing 10 fake Pan Am payroll checks in different towns. Abagnale escaped from the Cobb County jail and was picked up 4 days later in New York City. He was sentenced to ten years in 1971 for forging checks that totaled $1,448.60 and he received an additional two years for escaping from jail.[7][24]

In 1974, Abagnale was released on parole after he had served around two years of his 12-year sentence at Federal Correctional Institution in Petersburg, Virginia.[25] Unwilling to return to his family in New York, he left the choice of parole location up to the court, which decided that he would be paroled in Houston, Texas.[26]

After his release, Abagnale stated that he performed numerous jobs, including cook, grocer, and movie projectionist, but he was fired from most of these after it was discovered he had been hired without revealing his criminal past. He again posed as a pilot in 1974 to obtain a job at Camp Manison, a summer children’s camp in Texas where he was arrested for stealing cameras from his co-workers.[27] After he received only a fine, he obtained a position at a Houston-area orphanage by pretending to be a pilot with a master’s degree. This job had him finding foster homes for the children living at the orphanage. This ruse was eventually discovered by his parole officer, who swiftly removed him from his orphanage work and moved him into living quarters above his own garage so that he “could keep an eye on him”.[28] His next position was at Aetna, where he was fired and sued for check fraud.[7]

According to Abagnale, he approached a bank with an offer in 1975. He explained to the bank what he had done and offered to speak to the bank’s staff and show them various tricks that “paperhangers” use to defraud banks. His offer included the condition that if they did not find his speech helpful, they would owe him nothing; otherwise, they would owe him only $50, with an agreement that they would provide his name to other banks.[29] With that, he began a new career as a speaker and a security consultant.[2] During this time, he falsified his resume to show he had worked with the Los Angeles Police Department and Scotland Yard.[7]

In 1977, Abagnale gave public talks wherein he claimed that between the ages of 16 and 21 years old, he was a doctor in a Georgia hospital for one year, an assistant state attorney general for one year, a sociology professor for two semesters, and a Pan American airlines pilot for two years. In addition, Abagnale claimed that he recruited university coeds as Pan American stewardesses travelling with them for three months throughout Europe. He also claimed he eluded the FBI with a daring escape from a commercial airline toilet bowl, while the plane was taxiing at the John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York.[30][31] In 1978 Abagnale told a Honolulu Advertiser reporter that he was familiar with the toilet apparatus, squeezed himself through the opening, swung down through the lower hatch, landed on the pavement, ran across the runway and hailed a cab.[32] Abagnale claimed he moved the sewage container aside and that no one heard a thing: “I took off running. I thought they were right behind me. What I didn’t know was that the door was spring loaded and when it slammed shut the whole assembly fell back into place. Nobody heard anything because of the engines’ roar.”[33]

He moved his wife, Kelly, and their three sons to Tulsa, Oklahoma. He and his family lived in the same house for the next 25 years. After the sons left home for college and careers elsewhere, Kelly suggested that she and Frank should leave Tulsa. They agreed to move to Charleston, South Carolina.[26]

In 1976, he founded Abagnale & Associates,[2] which advises companies on secure documents. In 2015, Abagnale was named the AARP Fraud Watch Ambassador, where he helps “to provide online programs and community forums to educate consumers about ways to protect themselves from identity theft and cybercrime.” In 2018, he began co-hosting the AARP podcast The Perfect Scam about scammers and how they operate.[34]

He has appeared in the media a variety of times. This includes three times as guest on The Tonight Show, an appearance on To Tell the Truth in 1977 [35][36][37] and a regular slot on the British network TV series The Secret Cabaret in the 1990s.[38] The book about Abagnale, Catch Me If You Can, was turned into a movie of the same name by Steven Spielberg in 2002, featuring actor Leonardo DiCaprio as Abagnale. The real Abagnale made a cameo appearance in this film as a French police officer taking DiCaprio into custody.[39]

Veracity of claims[edit source]

During his appearances on television and in his speeches, Abagnale has often embellished his criminal exploits, stating that he was wanted in 12 countries, has worked extensively for the FBI and escaped several times from FBI custody. He also claimed that he cashed $2.5 million in bad checks and worked as an assistant attorney general and a hospital physician. In addition, he stated that he started a fake stewardess trainee program and logged over 2 million air miles disguised as a pilot.[7]

In public lectures describing his life story, Abagnale has consistently maintained that he was “arrested just once”, and that was in Montpellier, France.[40][41] However, public records show Abagnale was arrested in New York (multiple times), California, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Georgia, and Texas.[15][17][21][22][27][42]

Despite public records showing Abagnale targeted individuals and small family businesses,[15][17][20][21][22][27][43] Abagnale has long claimed publicly that he “never, ever ripped off any individuals”.[44] He made the same claim of never targetting individuals and small businesses to BBC journalist Sarah Montague and the Associated Press.[45][46] In 2002, Abagnale told the Star Tribune, “As long as I didn’t hurt anyone, people never considered me a real criminal, my victims were big corporations. I was a kid ripping off the establishment.”[47]

However, individuals criminally targeted by Abagnale have described the long-term consequences of victimization:[20]

He had a key to our front door, it was never recovered. We changed the lock. I fed him. I cooked. I don’t trust people as much anymore.— Charolette Parks, Abagnale victim interviewed April 27, 1981, The Advocate

Journalist Ira Perry was unable to find any evidence that Abagnale worked with the FBI; according to one retired FBI special agent in charge, Abagnale was caught trying to pass personal checks in 1978 several years after he claimed that he began working with the FBI.[24] Dating back to the 1980s Abagnale claimed that Joseph Shea, an FBI agent, had pursued him for 5 years (between 1965 and 1970).[48] Abagnale claimed that Shea befriended and supervised him during his parole.[7] However, when Catch Me If You Can was released in theatres, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that Abagnale and Shea only reunited in the late 1980s, almost 20 years after Shea arrested him. Abagnale spotted Shea at an anticrime seminar in Kansas City and sought out Shea to shake his hand.[49]

His claim that he passed the Louisiana bar exam, worked for Attorney General Jack P. F. Gremillion, and closed 33 cases, was debunked by several journalists in 1978.[24][50] There is no record of Abagnale ever being a member of the Louisiana Bar[51] and no evidence he ever worked as an assistant attorney general in Louisiana’s Attorney General Office. In 1978, the Louisiana State Bar Association reconciled all those who took the bar exam and concluded that Abagnale never took the exam using his own name or an alias; the State Attorney General‘s Office examined payments to all employees during the time Abagnale claimed he worked there and concluded that he never worked in the office using his name or an alias.[24] After Abagnale appeared on The Tonight Show, then-First Assistant Attorney General Ken DeJean gave a reporter a series of questions to ask Abagnale about the description of then-Attorney General Jack P. F. Gremillion. Abagnale failed to answer the questions correctly.[52]

Abagnale has publicly claimed an intelligence quotient (IQ) of 140: “I have an I.Q. of 140 and retain 90 percent of what I read. So by studying and memorizing the bar exam I was able to get the needed score.”[31] In 2021 Abagnale gave the keynote at the American Mensa Conference in Houston, Texas. The organizers claimed he was the subject of an FBI manhunt and cashed millions of dollars’ worth of checks while impersonating a pilot and doctor.[53]

One of Abagnale’s most notable claims was an alleged escape from the United States Penitentiary, Atlanta in 1971. In 1982 Abagnale told the press, “I was and still am the only and youngest man to escape from that prison.”[54] However, the Federal Bureau of Prisons confirmed that Abagnale was never housed in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary: “he was never admitted, so I don’t really see how he could have escaped” said acting warden Dwight Amstutz.[24]

In 1978, after Abagnale had been a featured speaker at an anti-crime seminar, a San Francisco Chronicle reporter looked into his assertions. Telephone calls to banks, schools, hospitals and other institutions Abagnale mentioned turned up no evidence of his cons under the aliases he used. Abagnale’s response was, “Due to the embarrassment involved, I doubt if anyone would confirm the information.” He later said he had changed the names.[55]

Further doubts were raised about Abagnale’s story after an October 1978 appearance on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, with a news article saying:

Abagnale is indeed a convicted confidence artist. But he is finding willing believers as he promotes and invents a more varied criminal past.— Stephen Hall, San Francisco Chronicle, “Johnny Is Conned”, October 6, 1978[56]

In December 1978, Abagnale’s claims were again investigated after he visited Oklahoma City for a talk.[24] As part of his investigation into the story, Perry spoke with Pan Am spokesman Bruce Haxthausen, who responded to the journalists’ enquiry saying:

This is the first we’ve heard of this, and we would have heard of or at least remember[ed] it if it had happened. You don’t forget $2.5 million in bad checks. I’d say this guy is as phony as a $3 bill.— Ira Perry, The Daily Oklahoman, “Inquiry Shows ‘Reformed’ Con Man Hasn’t Quit Yet”, December 10, 1978

In 2002, Abagnale addressed the issue of his story’s lack of truthfulness with a statement posted on his company’s website, which said in part: “I was interviewed by the co-writer only about four times. I believe he did a great job of telling the story, but he also over-dramatized and exaggerated some of the story. That was his style and what the editor wanted. He always reminded me that he was just telling a story and not writing my biography.”[57] However, Abagnale made the primary claims of working as a doctor for a year, an attorney for a year, a PhD professor, and his several escapes on national television in 1977 on the show To Tell the Truth.[37] He also made these claims in print media, namely the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, three years before the publication of his co-written autobiography, effectively nullifying the claim his aforementioned co-author, Stan Redding, exaggerated the story.[31]

In 2006, KSL journalist Scott Haws challenged Abagnale with his claim that he worked as a Ph.D-holding sociology professor at Brigham Young University (BYU) for two semesters. Abagnale claimed that he could not recall the details, and that his co-author Redding had exaggerated some things. Haws “refreshed Frank’s memory” and showed him his own words, including the Catch Me If You Can Moviebook and the credits that rolled at the end of the film Catch Me If You Can, where Abagnale, not Redding, made the BYU professor claim.[58] Abagnale conceded to Haws that he might have been a guest lecturer.[59]

So despite claiming to be a sociology professor in at least three books, two solely written by Abagnale himself, and an on-camera claim following the movie, it appears Abagnale as a BYU professor is mostly or entirely just another real fake.— Scott Haws, Did Frank Abignale [sic] Really Teach at BYU?, April 27, 2006, KSL-TV

Leading up to 2020, journalist Alan C. Logan conducted an in-depth investigation, as part of publishing a book, on Abagnale’s life story. Logan’s exhaustive search of earlier newspaper articles, and other public records, cast reasonable doubt on Abagnale’s story. Logan also discovered numerous administrative documents that contradicted many of Abagnale’s claims.[9] Logan’s investigation found that Abagnale’s claims were, for the most part, fabrications. Documents show that Abagnale was in Great Meadow Prison in Comstock, New York, between the ages of 17 and 20 (July 26, 1965, and December 24, 1968) as inmate #25367, the time frame during which Abagnale claims to have committed his most significant scams. Logan’s investigation uncovered numerous petty crimes that Abagnale has never acknowledged, and with Logan giving evidence to argue that many of Abagnale’s most famous scams in fact never occurred.[8][9]

Abagnale has told the press, “I was convicted on 2.5 million dollars’ worth of bad checks” and that he later hired a law firm to get all the money back to hotels and other companies.[60] However, federal court records show that Abagnale was convicted of forging 10 Pan American Airlines checks in five states (Texas, Arizona, Utah, California and North Carolina), totalling less than US$1,500.[7] Following parole, he claimed he went to work for the FBI. Logan found no evidence to support Abagnale’s claims, including the assertion that he was included in a coffee table book celebrating the 100th anniversary of the FBI.[9]

In many interviews and speeches Abagnale has claimed that he has earned millions of dollars from his patents.[40][61] However, the United States Patent and Trademark Office website shows that Abagnale as a person, and Abagnale and Associates as a business, hold no patents and they are not listed as an inventor on any patent.[62] In his cheque design patents, Canadian inventor Calin A. Sandru merely mentions in the Background section of the invention that KPMG and Abagnale and Associates are groups that affirm that cheque fraud is a significant problem.[63][64][65]

In 2020 Abagnale was confronted by one of his victims in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. When asked why he talks about being an attorney general and passing the bar exams, and yet failing to acknowledge his arrest and conviction in Baton Rouge, Abagnale said, “That’s because I work for the FBI.”[21] Abagnale claimed to the Star Tribune that he is an ethics instructor at the FBI Academy, located in Quantico, Virginia: “I teach ethics at the FBI academy, which is ironic, but years ago, someone at the Bureau said, ‘who better than you to do this?’—I try to teach young agents the importance of doing the right thing.”[66]

Logan, girded with public records, shared his findings in detail on the NPR program Watching America, August 13, 2021, broadcast on WHRO.[67]

Personal life[edit source]

Abagnale lives on Daniel Island, near Charleston, South Carolina, with his wife Kelly. They have three sons, Scott, Chris, and Sean.[68] Abagnale cites meeting his wife as the motivation for changing his life. He told author Paul Stenning that he met her while working undercover for the FBI when she was a cashier at a grocery store.[7][69]

Books[edit source]

- Catch Me If You Can, 1980. ISBN 978-0-7679-0538-1.

- The Art of the Steal, Broadway Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0-7679-0683-8.

- Real U Guide to Identity Theft, 2004. ISBN 978-1-932999-01-3.

- Stealing Your Life, Random House/Broadway Books, April 2007. ISBN 978-0-7679-2586-0.

- Scam Me If You Can, 2019. ISBN 978-0525538967.

See also[edit source]

- The Great Impostor, 1961 movie about Ferdinand Waldo Demara

- Elliot Castro, Scottish former fraudster

References[edit source]

- ^ “Abagnale’s First Lecture With New Biography”. The Galveston Daily News. January 25, 1977. p. 1. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Abagnale & Associates”. Abagnale & Associates. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ Stringfellow, Jonathan. “Infamous American Fraudster Frank Abagnale to speak at upcoming CSU event”. The Uproar. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ “New book claims Catch Me If You Can Frank Abagnale’s cons are fake”. www.msn.com. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ “Northern Ireland man exposes ‘Catch Me If You Can’ as work of fiction”. belfasttelegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Baker, Bob (December 28, 2002). “The truth? Just try to catch it if you can”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Alan C. Logan (December 2020). The Greatest Hoax on Earth: Catching Truth, While We Can. Indiana Landmarks. ISBN 978-1-73555-722-9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Well, Thomas (2021). “New book further debunks myth of scam artist Frank Abagnale, Jr. of ‘Catch Me if You Can’ book and movie”. Louisiana voice.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Lopez, Zavier (April 23, 2021). “Could this famous con man be lying about his story? A new book suggests he is”. WHYY-TV. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ “Catch Me If You Can: Frank Abagnale’s Story”. WGBH Educational Foundation. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ “FamilySearch.org”. ancestors.familysearch.org. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

- ^ “Paulette Noel Anton Abagnale (1926–2014) – Find A…” www.findagrave.com. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Abagnale, Frank (2000). Catch Me If You Can. New York City: Broadway Paperbacks. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7679-0538-1.

- ^ Bell, Rachael. “Skywayman: The Story of Frank W. Abagnale Jr”. TruTV Crime Library. Atlanta, Georgia: Turner Broadcasting Systems. Archived from the original on August 31, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e “Clipped From The Herald Statesman”. The Herald Statesman. July 16, 1965. p. 26. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Clipped From The Daily Times”. The Daily Times. July 16, 1965. p. 2. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Abagnale Arrested for Auto Theft”. Eureka Humboldt Standard. June 22, 1965. p. 11. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ “Vagrancy Charged Filed in City Against “Pilot””. The Advocate. February 15, 1969. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ “N.Y. Man Faces 2 Counts Here”. The State Times Advocate. February 15, 1969. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “BR Family Says Renowned Imposter Took Its Money”. The State Times Advocate. April 27, 1981. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “Did LABI pay a five-figure fee to get flim-flammed by self-proclaimed flim-flam artist at its annual luncheon Tuesday?”. Louisiana Voice. February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Logan, Alan (2020). The Greatest Hoax on Earth Catching Truth, While We Can. pp. 147–155. ISBN 9781736197400.

- ^ Holsen, Paul; II, Paul J. Holsen (July 11, 2014). Born in a Bottle of Beer. Createspace Independent Pub. ISBN 978-1-5003-8278-0.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g “Clipped From The Daily Oklahoman”. The Daily Oklahoman. December 14, 1978. p. 1. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Conway, Allan (2004). Analyze This: What Handwriting Reveals (1st ed.). PRC Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-85648-707-8.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Eaton, Kristi; Holton Dean, Anna (March 2019). “The Road to Fame: Frank Abagnale”. Tulsa People. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Clipped From The News”. The News. September 5, 1974. p. 1. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ “Uncovering the Con Man’s Biggest Lie”.

- ^ Abagnale, Frank W. (2001). The Art of the Steal. Broadway Books. ISBN 9780767910910.[page needed]

- ^ “Abagnale Makes Biographical Claims”. Plano Daily Star-Courier. February 11, 1977. p. 8. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Clipped From Fort Worth Star-Telegram”. Fort Worth Star-Telegram. November 9, 1977. p. 20. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ “Abagnale Claims Toilet Bowl Escape – Newspapers.com”. Newspapers.com. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ “The Great Imposter Biographical Claims”. The Times. February 21, 1982. p. 95. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ “Fraud Watch Ambassador Named”. August 27, 2015.

- ^ List of The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson episodes (1978)

- ^ “The Tonight Show”. December 3, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: To Tell The Truth (Joe Garagiola) (Imposter Frank Abagnale) (1977), retrieved July 25, 2021

- ^ Production company website, accessed April 19, 2021.

- ^ Van Luling, Todd (October 17, 2014). “11 Easter Eggs You Never Noticed in Your Favorite Movies”. HuffPost. TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “American Rhetoric: Frank Abagnale – National Automobile Dealers Association Convention Address”. www.americanrhetoric.com. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ “Talks at Google: Ep1 – Frank Abagnale | Catch Me If You Can”. talksatgoogle.libsyn.com. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ “Abagnale interacts with coeds using deception”. Arizona Daily Star. November 21, 1970. p. 34. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ “BR Family Says Renowned Imposter Took Its Money”. State Times Advocate. April 27, 1981. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ “Frank Abagnale claimed he never ripped off any individuals”. The Item. September 29, 1982. p. 5. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: BBC HardTalk Interview with Frank Abagnale, retrieved September 17, 2021

- ^ “Frank Abagnale claimed he never targeted ‘mom and pop’ stores”. The Ithaca Journal. November 20, 1980. p. 29. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ “Abagnale Claims Never Considered Real Criminal”. Star Tribune. December 22, 2002. pp. F7. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ “Clipped From Kenosha News”. Kenosha News. February 26, 1982. p. 7. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ “Clipped From The Atlanta Constitution”. The Atlanta Constitution. January 13, 2003. pp. C2. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ Hall, Stephen (October 6, 1978). “Johnny Is Conned”. No. 114th Year, No. 221. San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ “Attorney Status Search”. ladb.org. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Well, Thomas (April 27, 2021). “New book further debunks myth of scam artist Frank Abagnale, Jr. of ‘Catch Me if You Can’ book and movie”. Louisanavoice.com. Louisiana Voice.

- ^ “American Mensa’s World Gathering | Aug. 24–29, 2021”. ag.us.mensa.org. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ “Abagnale Claims Escape From Atlanta Federal Penitentiary”. Arizona Daily Sun. February 24, 1982. p. 6. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ Baker, Bob (December 6, 2002). “Portrait of the con artist as a young man”. newsthinking.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ^ Hall, Stephen (October 6, 1978). “Johnny Is Conned”. No. 114th Year, No. 221. San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ “Abagnale & Associates, Comments”. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ^ Steven Spielberg; Frank W. Abagnale; Andrew Cooper; Jeff Nathanson; Timothy Shaner (2002). Linda Sunshine (ed.). Catch me if you can : a Steven Spielberg film. New York: Newmarket Press. ISBN 1-55704-553-4. OCLC 51995375.

- ^ April 27, Posted-; A.m, 2006 at 11:54. “Did Frank Abignale Really Teach at BYU?”. www.ksl.com. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- ^ 1393354. “Charleston Home + Design Magazine – Spring 2014”. Issuu. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ Writer, NewsNet Staff (March 11, 2005). “The art of the steal”. The Daily Universe. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ “Patent Database Search Results: abagnale in US Patent Collection”. patft.uspto.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Sandru, Calin A. (February 28, 1997). “Apparatus and method for enhancing the security of negotiable documents”. United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Sandru, Calin A. (May 4, 2000). “Apparatus and method for enhancing the security of negotiable documents”. United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Sandru, Calin A. (July 1, 2002). “Apparatus and method for enhancing the security of negotiable instruments”. United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ “Abagnale Claims to be Ethics Instructor at FBI Academy”. Star Tribune. May 13, 2015. pp. D2. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ “WHRO Radio & TV Programs, Podcasts, Episodes”. mediaplayer.whro.org. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Hunt, Stephanie (September 2010). “Charleston Profile: Bona Fide”. Charleston Mag via abagnale.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2010. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ Stenning, Paul (November 24, 2013). Success – By Those Who’ve Made It. In Flight Books. p. 102. ISBN 978-1628475869.

External links[edit source]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frank Abagnale.

Wikiquote has quotations related to: Frank Abagnale -

Kevin Mitnick

Kevin David Mitnick (born August 6, 1963) is an American computer security consultant, author, and convicted hacker. He is best known for his high-profile 1995 arrest and five years in prison for various computer and communications-related crimes.[6]

Mitnick’s pursuit, arrest, trial, and sentence along with the associated journalism, books, and films were all controversial.[7][8]

He now runs the security firm Mitnick Security Consulting, LLC. He is also the Chief Hacking Officer and part owner[9] of the security awareness training company KnowBe4, as well as an active advisory board member at Zimperium,[10] a firm that develops a mobile intrusion prevention system.[11]

Contents

Early life and education[edit source]

Mitnick was born in Van Nuys, California, on August 6, 1963.[12][self-published source?] He grew up in Los Angeles and attended James Monroe High School in Los Angeles, California,[13] during which time he became an amateur radio operator.[14] He was later enrolled at Los Angeles Pierce College and USC.[13] For a time, he worked as a receptionist for Stephen S. Wise Temple.[13]

Career[edit source]

Computer hacking[edit source]

At age 12, Mitnick got a bus driver to tell him where he could buy his own ticket punch for “a school project”, and was then able to ride any bus in the greater LA area using unused transfer slips he found in a dumpster next to the bus company garage.[15]

Mitnick first gained unauthorized access to a computer network in 1979, at 16, when a friend gave him the phone number for the Ark, the computer system that Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) used for developing its RSTS/E operating system software.[16] He broke into DEC’s computer network and copied the company’s software, a crime for which he was charged and convicted in 1988. He was sentenced to 12 months in prison followed by three years of supervised release. Near the end of his supervised release, Mitnick hacked into Pacific Bell voicemail computers. After a warrant was issued for his arrest, Mitnick fled, becoming a fugitive for two-and-a-half years.[citation needed]

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, Mitnick gained unauthorized access to dozens of computer networks while he was a fugitive. He used cloned cellular phones to hide his location and, among other things, copied valuable proprietary software from some of the country’s largest cellular telephone and computer companies. Mitnick also intercepted and stole computer passwords, altered computer networks, and broke into and read private e-mails.[citation needed]

Arrest, conviction, and incarceration[edit source]

Supporters from 2600 Magazine distributed “Free Kevin” bumper stickers.[17]

After a well-publicized pursuit, the FBI arrested Mitnick on February 15, 1995, at his apartment in Raleigh, North Carolina, on federal offenses related to a two-and-a-half-year period of computer hacking which included computer and wire fraud.[18][19] He was found with cloned cellular phones, more than 100 cloned cellular phone codes, and multiple pieces of false identification.[20]

In December 1997, the Yahoo! website was hacked, displaying a message calling for Mitnick’s release. According to the message, all recent visitors of Yahoo!’s website had been infected with a computer worm that would wreak havoc on Christmas Day unless Mitnick was released. Yahoo! dismissed the claims as a hoax and said that the worm was nonexistent.[21][22]

Mitnick was charged with wire fraud (14 counts), possession of unauthorized access devices (8 counts), interception of wire or electronic communications, unauthorized access to a federal computer, and causing damage to a computer.[4]

In 1999, Mitnick pleaded guilty to four counts of wire fraud, two counts of computer fraud, and one count of illegally intercepting a wire communication, as part of a plea agreement before the United States District Court for the Central District of California in Los Angeles. He was sentenced to 46 months in prison plus 22 months for violating the terms of his 1989 supervised release sentence for computer fraud. He admitted to violating the terms of supervised release by hacking into Pacific Bell voicemail and other systems and to associating with known computer hackers, in this case co-defendant Lewis De Payne.[1][23]

Mitnick served five years in prison—four-and-a-half years’ pre-trial and eight months in solitary confinement—because, according to Mitnick, law enforcement officials convinced a judge that he had the ability to “start a nuclear war by whistling into a pay phone”,[24] implying that law enforcement told the judge that he could somehow dial into the NORAD modem via a payphone from prison and communicate with the modem by whistling to launch nuclear missiles.[25] In addition, a number of media outlets reported on the unavailability of kosher meals at the prison where he was incarcerated.[26]

He was released on January 21, 2000. During his supervised release, which ended on January 21, 2003, he was initially forbidden to use any communications technology other than a landline telephone.[27] Mitnick fought this decision in court, eventually winning a ruling in his favor, allowing him to access the Internet. Under the plea deal, Mitnick was also prohibited from profiting from films or books based on his criminal activity for seven years, under a special judicial Son of Sam law variation.

In December 2001, an FCC judge ruled that Mitnick was sufficiently rehabilitated to possess a federally issued amateur radio license.[28] Mitnick now runs Mitnick Security Consulting LLC, a computer security consultancy and is part owner of KnowBe4, provider of an integrated platform for security awareness training and simulated phishing testing.[29]

Controversy[edit source]

Mitnick’s criminal activities, arrest, and trial, along with the associated journalism, were all controversial.[7] Though Mitnick has been convicted of copying software unlawfully,[30] his supporters argue that his punishment was excessive and that many of the charges against him were fraudulent[31] and not based on actual losses.[32]

In his 2002 book, The Art of Deception, Mitnick states that he compromised computers solely by using passwords and codes that he gained by social engineering. He claims he did not use software programs or hacking tools for cracking passwords or otherwise exploiting computer or phone security.[citation needed]

John Markoff and Tsutomu Shimomura, who had both been part of the pursuit of Mitnick, wrote the book Takedown about Mitnick’s capture.[citation needed]

The case against Mitnick tested the new laws that had been enacted for dealing with computer crime, and it raised public awareness of security involving networked computers. The controversy remains, however, and the Mitnick story is often cited today as an example of the influence that newspapers and other media outlets can have on law enforcement personnel.[33]

Consulting[edit source]

Since 2000, Mitnick has been a paid security consultant, public speaker, and author. He does security consulting for, performs penetration testing services, and teaches Social Engineering classes to companies and government agencies. His company Mitnick Security Consulting is based in Las Vegas, Nevada[34] where he currently resides.

Media[edit source]

Adrian Lamo, Kevin Mitnick, and Kevin Poulsen (photo c. 2001)

In 2000, Skeet Ulrich and Russell Wong portrayed Kevin Mitnick and Tsutomu Shimomura, respectively, in the movie Track Down (known as Takedown outside the US), which was based on the book Takedown by John Markoff and Tsutomu Shimomura. The DVD was released in September 2004.[35] A 2001 documentary named Freedom Downtime was produced by 2600: The Hacker Quarterly in response to Takedown.[citation needed]

Mitnick’s story was a partial inspiration for Wizzywig, Ed Piskor‘s graphic novel about hackers.[citation needed]

Mitnick also appeared in Werner Herzog‘s documentary Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World (2016).

Books[edit source]

Written by Mitnick[edit source]

Mitnick is the co-author, with William L. Simon and Robert Vamosi, of four books, three on computer security and his autobiography:

- (2003) The Art of Deception: Controlling the Human Element of Security[36]

- (2005) The Art of Intrusion: The Real Stories Behind the Exploits of Hackers, Intruders & Deceivers[37]

- (2011) Ghost in the Wires: My Adventures as the World’s Most Wanted Hacker[38]

- (2017) The Art of Invisibility[39]

Authorized by Mitnick[edit source]

- (1996) The Fugitive Game: Online with Kevin Mitnick. In this book author Jonathan Littman presented Mitnick’s account of his story,[40] as John Markoff’s book Takedown (1996) and Jeff Goodell’s Cyberthief and the Samurai (1996) presented Shimomura’s side (when Mitnick was legally unable to publish and profit from his own story).

See also[edit source]

- Kevin Poulsen

- “My kung fu is stronger than yours“

- List of computer criminals

- The Secret History of Hacking

References[edit source]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gengler, Barbara (1999). “Super-hacker Kevin Mitnick takes a plea”. Computer Fraud & Security. 1999 (5): 6. doi:10.1016/S1361-3723(99)90141-0.

- ^ “Kevin Mitnick’s Federal Indictment”. Archived from the original on May 18, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ “#089 Fugitive Computer Hacker Arrested in North Carolina”. justice.gov. Archived from the original on June 13, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Kevin Mitnick Case: 1999 – No Bail, No Computer, Hacker Pleads Guilty”. jrank.org.

- ^ “HEARING DESIGNATION ORDER (FCC 01-359)” (PDF). Federal Communications Commission. December 21, 2001. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ^ “Kevin Mitnick sentenced to nearly four years in prison; computer hacker ordered to pay restitution to victim companies whose systems were compromised” (Press release). United States Attorney’s Office, Central District of California. August 9, 1999. Archived from the original on June 13, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Free Kevin, Kevin Freed”, Jan 21, 2000, Jason Kroll, Linux Journal

- ^ “Ex-hacker reveals tricks of the trade”. AsiaOne Digital. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015.

- ^ KnowBe4. “Kevin Mitnick Partners With KnowBe4”. www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ Darlene Storm (July 19, 2012). “Interview: World’s most famous hacker, Kevin Mitnick, on mobile security & Zimperium”. Computerworld. Archived from the original on December 26, 2013.

- ^ Alex Williams. “Zimperium Raises $8M For Mobile Security That Turns The Tables On Attackers”. TechCrunch. AOL.

- ^ Merritt, Tom (2012). Chronology of Tech History. Lulu.com. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-300-25307-5.[self-published source]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Mitnick, Kevin (2011). Ghost in the Wires: My Adventures as the World’s Most Wanted Hacker. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-03770-9.

- ^ Mills, Elinor. “Q&A: Kevin Mitnick, from ham operator to fugitive to consultant”. cnet.com. CNET. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- ^ Greene, Thomas C. (January 13, 2003). “Chapter One: Kevin Mitnick’s story”. The Register. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012.

- ^ “The Missing Chapter from The Art of Deception by Kevin Mitnick”. thememoryhole.org. Archived from the original on March 17, 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ “Freedom Downtime – The Story of Kevin Mitnick : 2600 Films : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive”. Internet Archive. October 23, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ “Fugitive computer hacker arrested in North Carolina” (Press release). United States Department of Justice. February 15, 1995. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012.

- ^ Colbert Report

- ^ Pnter, Christopher M.E. (March 2001). “Supervised Release and Probation Restrictions in Hacker Cases” (PDF). United States Attorneys’ USA Bulletin. Executive Office for United States Attorneys. 49 (2).

- ^ “Yahoo Hack: Heck of a Hoax”. Wired. December 9, 1997.

- ^ Original text posted to Yahoo’s website.

- ^ “Computer Hacker Kevin Mitnick Sentenced to Prison”. fas.org. June 27, 1997. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ Mills, Elinor (July 20, 2008). “Social Engineering 101: Mitnick and other hackers show how it’s done”. CNET News. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012.

- ^ “Famed hacker to Snowden: Watch out”. CNN.

- ^ “Life Not Kosher for Mitnick”. Wired. August 18, 1999. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012.

- ^ Bowker, Art. “Hackers, Sex Offenders, and All the Rest”. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ^ “F.C.C. Lets Convicted Hacker Go Back on Net”. The New York Times (Press release). December 27, 2002.

- ^ Noory, George (January 7, 2019). “Cybercrime & Security”. Coast to Coast AM. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ Miller, Greg (March 27, 1999). “Judge Accepts Mitnick’s Guilty Plea on 7 Counts”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ Randolph, Donald C. “About Kevin’s Case”. Free Kevin Mitnick. Archived from the original on April 24, 2006.

- ^ “Defense consolidated motion for sanctions and for reconsideration of motion for discovery and application for expert fees based upon new facts”. Free Kevin Mitnick. June 7, 1999. Archived from the original on December 22, 2005.

- ^ John Christensen (March 18, 1999). “The trials of Kevin Mitnick”. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ “Kevin Mitnick’s Security Advice”. Wired.

- ^ Skeet Ulrich, Russell Wong (2004). Track Down (DVD). Dimension Studios.

- ^ Mitnick, Kevin; Simon, William L. (October 2003). The Art of Deception: Controlling the Human Element of Security. Wiley Books. ISBN 978-0-7645-4280-0.

- ^ Mitnick, Kevin; Simon, William L. (December 27, 2005). The Art of Intrusion: The Real Stories Behind the Exploits of Hackers, Intruders & Deceivers. Wiley Books. ISBN 978-0-7645-6959-3.

- ^ Mitnick, Kevin; Simon, William L. (2011). Ghost in the Wires: My Adventures as the World’s Most Wanted Hacker. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-03770-9. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ Mitnick, Kevin; Vamosi, Robert (February 2017). The Art of Invisibility. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-3163-8049-2.

- ^ Hafner, Katie. “The Fugitive Game: Online with Kevin Mitnick: Jonathan Littman: Books”. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

Bibliography[edit source]

Movies[edit source]

Books[edit source]

- Kevin Mitnick with Robert Vamosi, The Art of Invisibility, 2017, Hardback ISBN 978-0-316-38049-2

- Kevin Mitnick and William L. Simon, Ghost in the Wires: My Adventures as the World’s Most Wanted Hacker, 2011, Hardback ISBN 978-0-316-03770-9

- Kevin Mitnick and William L. Simon, The Art of Intrusion: The Real Stories Behind The Exploits Of Hackers, Intruders, And Deceivers, 2005, Hardback ISBN 0-471-78266-1

- Kevin Mitnick, The Art of Deception: Controlling the Human Element of Security, 2002, Paperback ISBN 0-471-23712-4

- Jeff Goodell, The Cyberthief and the Samurai: The True Story of Kevin Mitnick-And the Man Who Hunted Him Down, 1996, ISBN 978-0-440-22205-7

- Tsutomu Shimomura, Takedown: The Pursuit and Capture of Kevin Mitnick, America’s Most Wanted Computer Outlaw-By the Man Who Did It, 1996, ISBN 0-7868-8913-6

- Jonathan Littman, The Fugitive Game: Online with Kevin Mitnick, 1996, ISBN 0-316-52858-7

- Katie Hafner and John Markoff, CYBERPUNK – Outlaws and Hackers on the Computer Frontier, 1995, ISBN 1-872180-94-9

Articles[edit source]

- Littman, Jonathan (June 2007). “The Invisible Digital Man” (PDF). Playboy. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016.

- Fost, Dan (May 4, 2000). “Movie About Notorious Hacker Inspires a Tangle of Suits and Subplots”. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- Darell, Khin. “From Being Hunted By The FBI To Working Alongside Them- Kevin Mitnick”. Appknox. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- Ehrlich, Thomas. “Renowned security expert Kevin Mitnick can steal your identity in 3 minutes”. Forbes. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

-

Sigmund Freud

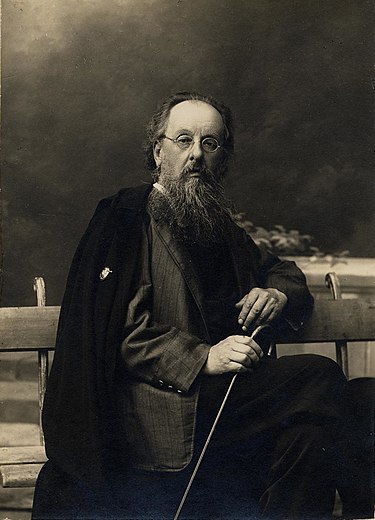

Sigmund Freud (/frɔɪd/ FROYD,[3] German: [ˈziːkmʊnt ˈfʁɔʏ̯t]; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies in the psyche through dialogue between a patient and a psychoanalyst.[4]

Freud was born to Galician Jewish parents in the Moravian town of Freiberg, in the Austrian Empire. He qualified as a doctor of medicine in 1881 at the University of Vienna.[5][6] Upon completing his habilitation in 1885, he was appointed a docent in neuropathology and became an affiliated professor in 1902.[7] Freud lived and worked in Vienna, having set up his clinical practice there in 1886. In 1938, Freud left Austria to escape Nazi persecution. He died in exile in the United Kingdom in 1939.

In founding psychoanalysis, Freud developed therapeutic techniques such as the use of free association and discovered transference, establishing its central role in the analytic process. Freud’s redefinition of sexuality to include its infantile forms led him to formulate the Oedipus complex as the central tenet of psychoanalytical theory.[8] His analysis of dreams as wish-fulfillments provided him with models for the clinical analysis of symptom formation and the underlying mechanisms of repression. On this basis, Freud elaborated his theory of the unconscious and went on to develop a model of psychic structure comprising id, ego and super-ego.[9] Freud postulated the existence of libido, sexualised energy with which mental processes and structures are invested and which generates erotic attachments, and a death drive, the source of compulsive repetition, hate, aggression, and neurotic guilt.[10] In his later works, Freud developed a wide-ranging interpretation and critique of religion and culture.

Though in overall decline as a diagnostic and clinical practice, psychoanalysis remains influential within psychology, psychiatry, and psychotherapy, and across the humanities. It thus continues to generate extensive and highly contested debate concerning its therapeutic efficacy, its scientific status, and whether it advances or hinders the feminist cause.[11] Nonetheless, Freud’s work has suffused contemporary Western thought and popular culture. W. H. Auden‘s 1940 poetic tribute to Freud describes him as having created “a whole climate of opinion / under whom we conduct our different lives”.[12]

Contents

- 1Biography

- 2Ideas

- 3Legacy

- 4In popular culture

- 5Works

- 6Correspondence

- 7See also

- 8Notes

- 9References

- 10Further reading

- 11External links

Biography[edit source]

Early life and education[edit source]

Freud’s birthplace, a rented room in a locksmith’s house, Freiberg, Austrian Empire (later Příbor, Czech Republic)Freud (aged 16) and his mother, Amalia, in 1872

Sigmund Freud was born to Ashkenazi Jewish parents in the Moravian town of Freiberg,[13][14] in the Austrian Empire (now Příbor, Czech Republic), the first of eight children.[15] Both of his parents were from Galicia, a historic province straddling modern-day West Ukraine and southeast Poland. His father, Jakob Freud (1815–1896), a wool merchant, had two sons, Emanuel (1833–1914) and Philipp (1836–1911), by his first marriage. Jakob’s family were Hasidic Jews and, although Jakob himself had moved away from the tradition, he came to be known for his Torah study. He and Freud’s mother, Amalia Nathansohn, who was 20 years younger and his third wife, were married by Rabbi Isaac Noah Mannheimer on 29 July 1855.[16] They were struggling financially and living in a rented room, in a locksmith’s house at Schlossergasse 117 when their son Sigmund was born.[17] He was born with a caul, which his mother saw as a positive omen for the boy’s future.[18]

In 1859, the Freud family left Freiberg. Freud’s half-brothers immigrated to Manchester, England, parting him from the “inseparable” playmate of his early childhood, Emanuel’s son, John.[19] Jakob Freud took his wife and two children (Freud’s sister, Anna, was born in 1858; a brother, Julius born in 1857, had died in infancy) firstly to Leipzig and then in 1860 to Vienna where four sisters and a brother were born: Rosa (b. 1860), Marie (b. 1861), Adolfine (b. 1862), Paula (b. 1864), Alexander (b. 1866). In 1865, the nine-year-old Freud entered the Leopoldstädter Kommunal-Realgymnasium, a prominent high school. He proved to be an outstanding pupil and graduated from the Matura in 1873 with honors. He loved literature and was proficient in German, French, Italian, Spanish, English, Hebrew, Latin and Greek.[20]

Freud entered the University of Vienna at age 17. He had planned to study law, but joined the medical faculty at the university, where his studies included philosophy under Franz Brentano, physiology under Ernst Brücke, and zoology under Darwinist professor Carl Claus.[21] In 1876, Freud spent four weeks at Claus’s zoological research station in Trieste, dissecting hundreds of eels in an inconclusive search for their male reproductive organs.[22] In 1877, Freud moved to Ernst Brücke’s physiology laboratory where he spent six years comparing the brains of humans and other vertebrates with those of frogs and invertebrates such as crayfish and lampreys. His research work on the biology of nervous tissue proved seminal for the subsequent discovery of the neuron in the 1890s.[23] Freud’s research work was interrupted in 1879 by the obligation to undertake a year’s compulsory military service. The lengthy downtimes enabled him to complete a commission to translate four essays from John Stuart Mill‘s collected works.[24] He graduated with an MD in March 1881.[25]

Early career and marriage[edit source]

In 1882, Freud began his medical career at Vienna General Hospital. His research work in cerebral anatomy led to the publication in 1884 of an influential paper on the palliative effects of cocaine, and his work on aphasia would form the basis of his first book On Aphasia: A Critical Study, published in 1891.[26] Over a three-year period, Freud worked in various departments of the hospital. His time spent in Theodor Meynert‘s psychiatric clinic and as a locum in a local asylum led to an increased interest in clinical work. His substantial body of published research led to his appointment as a university lecturer or docent in neuropathology in 1885, a non-salaried post but one which entitled him to give lectures at the University of Vienna.[27]

In 1886, Freud resigned his hospital post and entered private practice specializing in “nervous disorders”. The same year he married Martha Bernays, the granddaughter of Isaac Bernays, a chief rabbi in Hamburg. They had six children: Mathilde (b. 1887), Jean-Martin (b. 1889), Oliver (b. 1891), Ernst (b. 1892), Sophie (b. 1893), and Anna (b. 1895). From 1891 until they left Vienna in 1938, Freud and his family lived in an apartment at Berggasse 19, near Innere Stadt, a historical district of Vienna.Freud’s home at Berggasse 19, Vienna

In 1896, Minna Bernays, Martha Freud’s sister, became a permanent member of the Freud household after the death of her fiancé. The close relationship she formed with Freud led to rumours, started by Carl Jung, of an affair. The discovery of a Swiss hotel guest-book entry for 13 August 1898, signed by Freud whilst travelling with his sister-in-law, has been presented as evidence of the affair.[28]

Freud began smoking tobacco at age 24; initially a cigarette smoker, he became a cigar smoker. He believed smoking enhanced his capacity to work and that he could exercise self-control in moderating it. Despite health warnings from colleague Wilhelm Fliess, he remained a smoker, eventually suffering a buccal cancer.[29] Freud suggested to Fliess in 1897 that addictions, including that to tobacco, were substitutes for masturbation, “the one great habit.”[30]

Freud had greatly admired his philosophy tutor, Brentano, who was known for his theories of perception and introspection. Brentano discussed the possible existence of the unconscious mind in his Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint (1874). Although Brentano denied its existence, his discussion of the unconscious probably helped introduce Freud to the concept.[31] Freud owned and made use of Charles Darwin‘s major evolutionary writings, and was also influenced by Eduard von Hartmann‘s The Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869). Other texts of importance to Freud were by Fechner and Herbart,[32] with the latter’s Psychology as Science arguably considered to be of underrated significance in this respect.[33] Freud also drew on the work of Theodor Lipps, who was one of the main contemporary theorists of the concepts of the unconscious and empathy.[34]

Though Freud was reluctant to associate his psychoanalytic insights with prior philosophical theories, attention has been drawn to analogies between his work and that of both Schopenhauer[35] and Nietzsche. In 1908, Freud said that he occasionally read Nietzsche, and had a strong fascination for his writings, but did not study him, because he found Nietzsche’s “intuitive insights” resembled too much his own work at the time, and also because he was overwhelmed by the “wealth of ideas” he encountered when he read Nietzsche. Freud sometimes would deny the influence of Nietzsche’s ideas. One historian quotes Peter L. Rudnytsky, who says that based on Freud’s correspondence with his adolescent friend Eduard Silberstein, Freud read Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy and probably the first two of the Untimely Meditations when he was seventeen.[36][37] In 1900, the year of Nietzsche’s death, Freud bought his collected works; he told his friend, Fliess, that he hoped to find in Nietzsche’s works “the words for much that remains mute in me.” Later, he said he had not yet opened them.[38] Freud came to treat Nietzsche’s writings “as texts to be resisted far more than to be studied.” His interest in philosophy declined after he had decided on a career in neurology.[39]

Freud read William Shakespeare in English throughout his life, and it has been suggested that his understanding of human psychology may have been partially derived from Shakespeare’s plays.[40]

Freud’s Jewish origins and his allegiance to his secular Jewish identity were of significant influence in the formation of his intellectual and moral outlook, especially concerning his intellectual non-conformism, as he was the first to point out in his Autobiographical Study.[41] They would also have a substantial effect on the content of psychoanalytic ideas, particularly in respect of their common concerns with depth interpretation and “the bounding of desire by law”.[42]

Development of psychoanalysis[edit source]

André Brouillet‘s A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière (1887) depicting a Charcot demonstration. Freud had a lithograph of this painting placed over the couch in his consulting rooms.[43]

In October 1885, Freud went to Paris on a three-month fellowship to study with Jean-Martin Charcot, a renowned neurologist who was conducting scientific research into hypnosis. He was later to recall the experience of this stay as catalytic in turning him toward the practice of medical psychopathology and away from a less financially promising career in neurology research.[44] Charcot specialized in the study of hysteria and susceptibility to hypnosis, which he frequently demonstrated with patients on stage in front of an audience.

Once he had set up in private practice back in Vienna in 1886, Freud began using hypnosis in his clinical work. He adopted the approach of his friend and collaborator, Josef Breuer, in a type of hypnosis that was different from the French methods he had studied, in that it did not use suggestion. The treatment of one particular patient of Breuer’s proved to be transformative for Freud’s clinical practice. Described as Anna O., she was invited to talk about her symptoms while under hypnosis (she would coin the phrase “talking cure” for her treatment). In the course of talking in this way, her symptoms became reduced in severity as she retrieved memories of traumatic incidents associated with their onset.

The inconsistent results of Freud’s early clinical work eventually led him to abandon hypnosis, having concluded that more consistent and effective symptom relief could be achieved by encouraging patients to talk freely, without censorship or inhibition, about whatever ideas or memories occurred to them. In conjunction with this procedure, which he called “free association“, Freud found that patients’ dreams could be fruitfully analyzed to reveal the complex structuring of unconscious material and to demonstrate the psychic action of repression which, he had concluded, underlay symptom formation. By 1896 he was using the term “psychoanalysis” to refer to his new clinical method and the theories on which it was based.[45]Approach to Freud’s consulting rooms at Berggasse 19

Freud’s development of these new theories took place during a period in which he experienced heart irregularities, disturbing dreams and periods of depression, a “neurasthenia” which he linked to the death of his father in 1896[46] and which prompted a “self-analysis” of his own dreams and memories of childhood. His explorations of his feelings of hostility to his father and rivalrous jealousy over his mother’s affections led him to fundamentally revise his theory of the origin of the neuroses.

Based on his early clinical work, Freud had postulated that unconscious memories of sexual molestation in early childhood were a necessary precondition for the psychoneuroses (hysteria and obsessional neurosis), a formulation now known as Freud’s seduction theory.[47] In the light of his self-analysis, Freud abandoned the theory that every neurosis can be traced back to the effects of infantile sexual abuse, now arguing that infantile sexual scenarios still had a causative function, but it did not matter whether they were real or imagined and that in either case, they became pathogenic only when acting as repressed memories.[48]

This transition from the theory of infantile sexual trauma as a general explanation of how all neuroses originate to one that presupposes autonomous infantile sexuality provided the basis for Freud’s subsequent formulation of the theory of the Oedipus complex.[49]

Freud described the evolution of his clinical method and set out his theory of the psychogenetic origins of hysteria, demonstrated in several case histories, in Studies on Hysteria published in 1895 (co-authored with Josef Breuer). In 1899, he published The Interpretation of Dreams in which, following a critical review of existing theory, Freud gives detailed interpretations of his own and his patients’ dreams in terms of wish-fulfillments made subject to the repression and censorship of the “dream-work”. He then sets out the theoretical model of mental structure (the unconscious, pre-conscious and conscious) on which this account is based. An abridged version, On Dreams, was published in 1901. In works that would win him a more general readership, Freud applied his theories outside the clinical setting in The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901) and Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (1905).[50] In Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, published in 1905, Freud elaborates his theory of infantile sexuality, describing its “polymorphous perverse” forms and the functioning of the “drives”, to which it gives rise, in the formation of sexual identity.[51] The same year he published Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria, which became one of his more famous and controversial case studies.[52]

Relationship with Fliess[edit source]

During this formative period of his work, Freud valued and came to rely on the intellectual and emotional support of his friend Wilhelm Fliess, a Berlin-based ear, nose, and throat specialist whom he had first met in 1887. Both men saw themselves as isolated from the prevailing clinical and theoretical mainstream because of their ambitions to develop radical new theories of sexuality. Fliess developed highly eccentric theories of human biorhythms and a nasogenital connection which are today considered pseudoscientific. He shared Freud’s views on the importance of certain aspects of sexuality – masturbation, coitus interruptus, and the use of condoms – in the etiology of what was then called the “actual neuroses,” primarily neurasthenia and certain physically manifested anxiety symptoms.[53] They maintained an extensive correspondence from which Freud drew on Fliess’s speculations on infantile sexuality and bisexuality to elaborate and revise his own ideas. His first attempt at a systematic theory of the mind, his Project for a Scientific Psychology was developed as a metapsychology with Fliess as interlocutor.[54] However, Freud’s efforts to build a bridge between neurology and psychology were eventually abandoned after they had reached an impasse, as his letters to Fliess reveal,[55] though some ideas of the Project were to be taken up again in the concluding chapter of The Interpretation of Dreams.[56]

Freud had Fliess repeatedly operate on his nose and sinuses to treat “nasal reflex neurosis”,[57] and subsequently referred his patient Emma Eckstein to him. According to Freud, her history of symptoms included severe leg pains with consequent restricted mobility, as well as stomach and menstrual pains. These pains were, according to Fliess’s theories, caused by habitual masturbation which, as the tissue of the nose and genitalia were linked, was curable by removal of part of the middle turbinate.[58][59] Fliess’s surgery proved disastrous, resulting in profuse, recurrent nasal bleeding; he had left a half-metre of gauze in Eckstein’s nasal cavity whose subsequent removal left her permanently disfigured. At first, though aware of Fliess’s culpability and regarding the remedial surgery in horror, Freud could bring himself only to intimate delicately in his correspondence with Fliess the nature of his disastrous role, and in subsequent letters maintained a tactful silence on the matter or else returned to the face-saving topic of Eckstein’s hysteria. Freud ultimately, in light of Eckstein’s history of adolescent self-cutting and irregular nasal (and menstrual) bleeding, concluded that Fliess was “completely without blame”, as Eckstein’s post-operative haemorrhages were hysterical “wish-bleedings” linked to “an old wish to be loved in her illness” and triggered as a means of “rearousing [Freud’s] affection”. Eckstein nonetheless continued her analysis with Freud. She was restored to full mobility and went on to practice psychoanalysis herself.[60][61][58]

Freud, who had called Fliess “the Kepler of biology”, later concluded that a combination of a homoerotic attachment and the residue of his “specifically Jewish mysticism” lay behind his loyalty to his Jewish friend and his consequent over-estimation of both his theoretical and clinical work. Their friendship came to an acrimonious end with Fliess angry at Freud’s unwillingness to endorse his general theory of sexual periodicity and accusing him of collusion in the plagiarism of his work. After Fliess failed to respond to Freud’s offer of collaboration over the publication of his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality in 1906, their relationship came to an end.[62]

Early followers[edit source]

Group photo 1909 in front of Clark University. Front row: Sigmund Freud, G. Stanley Hall, Carl Jung; back row: Abraham Brill, Ernest Jones, Sándor Ferenczi

In 1902, Freud, at last, realised his long-standing ambition to be made a university professor. The title “professor extraordinarius”[63] was important to Freud for the recognition and prestige it conferred, there being no salary or teaching duties attached to the post (he would be granted the enhanced status of “professor ordinarius” in 1920).[64] Despite support from the university, his appointment had been blocked in successive years by the political authorities and it was secured only with the intervention of one of his more influential ex-patients, a Baroness Marie Ferstel, who (supposedly) had to bribe the minister of education with a valuable painting.[65]

With his prestige thus enhanced, Freud continued with the regular series of lectures on his work which, since the mid-1880s as a docent of Vienna University, he had been delivering to small audiences every Saturday evening at the lecture hall of the university’s psychiatric clinic.[66]

From the autumn of 1902, a number of Viennese physicians who had expressed interest in Freud’s work were invited to meet at his apartment every Wednesday afternoon to discuss issues relating to psychology and neuropathology.[67] This group was called the Wednesday Psychological Society (Psychologische Mittwochs-Gesellschaft) and it marked the beginnings of the worldwide psychoanalytic movement.[68]

Freud founded this discussion group at the suggestion of the physician Wilhelm Stekel. Stekel had studied medicine at the University of Vienna under Richard von Krafft-Ebing. His conversion to psychoanalysis is variously attributed to his successful treatment by Freud for a sexual problem or as a result of his reading The Interpretation of Dreams, to which he subsequently gave a positive review in the Viennese daily newspaper Neues Wiener Tagblatt.[69]

The other three original members whom Freud invited to attend, Alfred Adler, Max Kahane, and Rudolf Reitler, were also physicians[70] and all five were Jewish by birth.[71] Both Kahane and Reitler were childhood friends of Freud. Kahane had attended the same secondary school and both he and Reitler went to university with Freud. They had kept abreast of Freud’s developing ideas through their attendance at his Saturday evening lectures.[72] In 1901, Kahane, who first introduced Stekel to Freud’s work,[66] had opened an out-patient psychotherapy institute of which he was the director in Bauernmarkt, in Vienna.[67] In the same year, his medical textbook, Outline of Internal Medicine for Students and Practicing Physicians, was published. In it, he provided an outline of Freud’s psychoanalytic method.[66] Kahane broke with Freud and left the Wednesday Psychological Society in 1907 for unknown reasons and in 1923 committed suicide.[73] Reitler was the director of an establishment providing thermal cures in Dorotheergasse which had been founded in 1901.[67] He died prematurely in 1917. Adler, regarded as the most formidable intellect among the early Freud circle, was a socialist who in 1898 had written a health manual for the tailoring trade. He was particularly interested in the potential social impact of psychiatry.[74]

Max Graf, a Viennese musicologist and father of “Little Hans“, who had first encountered Freud in 1900 and joined the Wednesday group soon after its initial inception,[75] described the ritual and atmosphere of the early meetings of the society:

The gatherings followed a definite ritual. First one of the members would present a paper. Then, black coffee and cakes were served; cigars and cigarettes were on the table and were consumed in great quantities. After a social quarter of an hour, the discussion would begin. The last and decisive word was always spoken by Freud himself. There was the atmosphere of the foundation of a religion in that room. Freud himself was its new prophet who made the heretofore prevailing methods of psychological investigation appear superficial.[74]

Carl Jung in 1910

By 1906, the group had grown to sixteen members, including Otto Rank, who was employed as the group’s paid secretary.[74] In the same year, Freud began a correspondence with Carl Gustav Jung who was by then already an academically acclaimed researcher into word-association and the Galvanic Skin Response, and a lecturer at Zurich University, although still only an assistant to Eugen Bleuler at the Burghölzli Mental Hospital in Zürich.[76][77] In March 1907, Jung and Ludwig Binswanger, also a Swiss psychiatrist, travelled to Vienna to visit Freud and attend the discussion group. Thereafter, they established a small psychoanalytic group in Zürich. In 1908, reflecting its growing institutional status, the Wednesday group was reconstituted as the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society[78] with Freud as president, a position he relinquished in 1910 in favor of Adler in the hope of neutralizing his increasingly critical standpoint.[79]

The first woman member, Margarete Hilferding, joined the Society in 1910[80] and the following year she was joined by Tatiana Rosenthal and Sabina Spielrein who were both Russian psychiatrists and graduates of the Zürich University medical school. Before the completion of her studies, Spielrein had been a patient of Jung at the Burghölzli and the clinical and personal details of their relationship became the subject of an extensive correspondence between Freud and Jung. Both women would go on to make important contributions to the work of the Russian Psychoanalytic Society founded in 1910.[81]

Freud’s early followers met together formally for the first time at the Hotel Bristol, Salzburg on 27 April 1908. This meeting, which was retrospectively deemed to be the first International Psychoanalytic Congress,[82] was convened at the suggestion of Ernest Jones, then a London-based neurologist who had discovered Freud’s writings and begun applying psychoanalytic methods in his clinical work. Jones had met Jung at a conference the previous year and they met up again in Zürich to organize the Congress. There were, as Jones records, “forty-two present, half of whom were or became practicing analysts.”[83] In addition to Jones and the Viennese and Zürich contingents accompanying Freud and Jung, also present and notable for their subsequent importance in the psychoanalytic movement were Karl Abraham and Max Eitingon from Berlin, Sándor Ferenczi from Budapest and the New York-based Abraham Brill.

Important decisions were taken at the Congress to advance the impact of Freud’s work. A journal, the Jahrbuch für psychoanalytische und psychopathologishe Forschungen, was launched in 1909 under the editorship of Jung. This was followed in 1910 by the monthly Zentralblatt für Psychoanalyse edited by Adler and Stekel, in 1911 by Imago, a journal devoted to the application of psychoanalysis to the field of cultural and literary studies edited by Rank and in 1913 by the Internationale Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse, also edited by Rank.[84] Plans for an international association of psychoanalysts were put in place and these were implemented at the Nuremberg Congress of 1910 where Jung was elected, with Freud’s support, as its first president.

Freud turned to Brill and Jones to further his ambition to spread the psychoanalytic cause in the English-speaking world. Both were invited to Vienna following the Salzburg Congress and a division of labour was agreed with Brill given the translation rights for Freud’s works, and Jones, who was to take up a post at the University of Toronto later in the year, tasked with establishing a platform for Freudian ideas in North American academic and medical life.[85] Jones’s advocacy prepared the way for Freud’s visit to the United States, accompanied by Jung and Ferenczi, in September 1909 at the invitation of Stanley Hall, president of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, where he gave five lectures on psychoanalysis.[86]

The event, at which Freud was awarded an Honorary Doctorate, marked the first public recognition of Freud’s work and attracted widespread media interest. Freud’s audience included the distinguished neurologist and psychiatrist James Jackson Putnam, Professor of Diseases of the Nervous System at Harvard, who invited Freud to his country retreat where they held extensive discussions over a period of four days. Putnam’s subsequent public endorsement of Freud’s work represented a significant breakthrough for the psychoanalytic cause in the United States.[86] When Putnam and Jones organised the founding of the American Psychoanalytic Association in May 1911 they were elected president and secretary respectively. Brill founded the New York Psychoanalytic Society the same year. His English translations of Freud’s work began to appear from 1909.

Resignations from the IPA[edit source]

Some of Freud’s followers subsequently withdrew from the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) and founded their own schools.

From 1909, Adler’s views on topics such as neurosis began to differ markedly from those held by Freud. As Adler’s position appeared increasingly incompatible with Freudianism, a series of confrontations between their respective viewpoints took place at the meetings of the Viennese Psychoanalytic Society in January and February 1911. In February 1911, Adler, then the president of the society, resigned his position. At this time, Stekel also resigned from his position as vice president of the society. Adler finally left the Freudian group altogether in June 1911 to found his own organization with nine other members who had also resigned from the group.[87] This new formation was initially called Society for Free Psychoanalysis but it was soon renamed the Society for Individual Psychology. In the period after World War I, Adler became increasingly associated with a psychological position he devised called individual psychology.[88]The committee in 1922 (from left to right): Otto Rank, Sigmund Freud, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, Sándor Ferenczi, Ernest Jones, and Hanns Sachs

In 1912, Jung published Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido (published in English in 1916 as Psychology of the Unconscious) making it clear that his views were taking a direction quite different from those of Freud. To distinguish his system from psychoanalysis, Jung called it analytical psychology.[89] Anticipating the final breakdown of the relationship between Freud and Jung, Ernest Jones initiated the formation of a Secret Committee of loyalists charged with safeguarding the theoretical coherence and institutional legacy of the psychoanalytic movement. Formed in the autumn of 1912, the Committee comprised Freud, Jones, Abraham, Ferenczi, Rank, and Hanns Sachs. Max Eitingon joined the committee in 1919. Each member pledged himself not to make any public departure from the fundamental tenets of psychoanalytic theory before he had discussed his views with the others. After this development, Jung recognised that his position was untenable and resigned as editor of the Jarhbuch and then as president of the IPA in April 1914. The Zürich Society withdrew from the IPA the following July.[90]

Later the same year, Freud published a paper entitled “The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement“, the German original being first published in the Jahrbuch, giving his view on the birth and evolution of the psychoanalytic movement and the withdrawal of Adler and Jung from it.