-

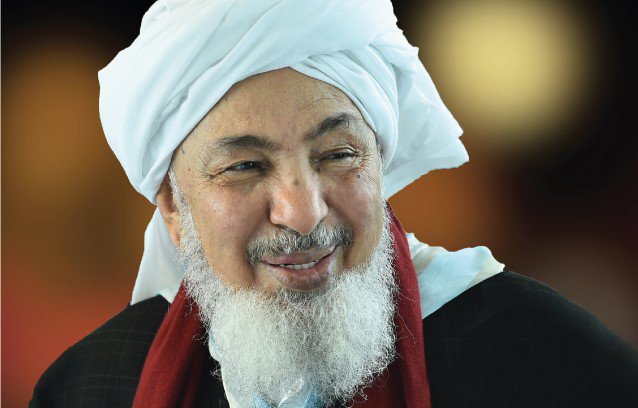

Billy Graham

William Franklin Graham Jr. (November 7, 1918 – February 21, 2018) was an American evangelist, a prominent evangelical Christian figure, and an ordained Southern Baptist minister who became well known internationally in the late 1940s. One of his biographers has placed him “among the most influential Christian leaders” of the 20th century.[2]

As a preacher, he held large indoor and outdoor rallies with sermons that were broadcast on radio and television; some were still being re-broadcast into the 21st century.[3] In his six decades on television, Graham hosted annual “Crusades“, evangelistic campaigns that ran from 1947 until his retirement in 2005. He also hosted the radio show Hour of Decision from 1950 to 1954. He repudiated racial segregation[4] and insisted on racial integration for his revivals and crusades, starting in 1953; he also invited Martin Luther King Jr. to preach jointly at a revival in New York City in 1957. In addition to his religious aims, he helped shape the worldview of a huge number of people who came from different backgrounds, leading them to find a relationship between the Bible and contemporary secular viewpoints. According to his website, Graham preached to live audiences of 210 million people in more than 185 countries and territories through various meetings, including BMS World Mission and Global Mission.[5]

Graham was a spiritual adviser to U.S. presidents, and he provided spiritual counsel for every president from Harry S. Truman (33rd) to Barack Obama (44th).[6] He was particularly close to Dwight D. Eisenhower, Lyndon B. Johnson (one of Graham’s closest friends),[7] and Richard Nixon.[8] He was also lifelong friends with another televangelist, the founding pastor of the Crystal Cathedral, Robert Schuller, whom Graham talked into starting his own television ministry.[9]

Graham operated a variety of media and publishing outlets.[10] According to his staff, more than 3.2 million people have responded to the invitation at Billy Graham Crusades to “accept Jesus Christ as their personal savior“. Graham’s evangelism was appreciated by mainline Protestant denominations, as he encouraged those mainline Protestants who were converted to his evangelical message to remain within or return to their mainline churches.[11][12] Despite his early suspicions and apprehension, common among contemporaneous evangelical Protestants, towards Roman Catholicism, Graham eventually developed amicable ties with many American Catholic Church figures and later encouraged unity between Roman Catholics and Protestants.[13] As of 2008, Graham’s estimated lifetime audience, including radio and television broadcasts, topped 2.2 billion. Because of his crusades, Graham preached the gospel to more people in person than anyone in the history of Christianity.[10] Graham was on Gallup’s list of most admired men and women a record 61 times.[14] Grant Wacker writes that by the mid-1960s, he had become the “Great Legitimator”: “By then his presence conferred status on presidents, acceptability on wars, shame on racial prejudice, desirability on decency, dishonor on indecency, and prestige on civic events.”[15]

Contents

- 1Early life

- 2Multiple roles

- 3Later life

- 4Politics

- 5Controversial views

- 6Awards and honors

- 7Media portrayals

- 8Works

- 9Personal life

- 10Death

- 11References

- 12Literature

- 13Further reading

- 14External links

Early life[edit source]

William Franklin Graham Jr. was born on November 7, 1918, in the downstairs bedroom of a farmhouse near Charlotte, North Carolina.[16] He was of Scots-Irish descent and was the eldest of four children born to Morrow (née Coffey) and William Franklin Graham Sr., a dairy farmer.[16] Graham was raised on a family dairy farm with his two younger sisters, Catherine Morrow and Jean and a younger brother, Melvin Thomas.[17] When he was nine years old, the family moved about 75 yards (69 m) from their white frame house to a newly built red brick home.[18][16] He was raised by his parents in the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church.[16][19] Graham attended the Sharon Grammar School.[20] He started to read books from an early age and loved to read novels for boys, especially Tarzan.[16] Like Tarzan, he would hang on the trees and gave the popular Tarzan yell. According to his father, that yelling had led him to become a minister.[21] Graham was 15 when Prohibition ended in December 1933, and his father forced him and his sister Katherine to drink beer until they became sick. This created such an aversion that Graham and his sister avoided alcohol and drugs for the rest of their lives.[22]

Graham had been turned down for membership in a local youth group for being “too worldly”.[22] Albert McMakin, who worked on the Graham farm, persuaded him to go and see the evangelist Mordecai Ham.[10] According to his autobiography, Graham was 16 in 1934 when he was converted during a series of revival meetings that Ham led in Charlotte.[23][24]

After graduating from Sharon High School in May 1936, Graham attended Bob Jones College. After one semester, he found that the coursework and rules were too legalistic.[22] At this time he was influenced and inspired by Pastor Charley Young from Eastport Bible Church. He was almost expelled, but Bob Jones Sr. warned him not to throw his life away: “At best, all you could amount to would be a poor country Baptist preacher somewhere out in the sticks … You have a voice that pulls. God can use that voice of yours. He can use it mightily.”[22]

In 1937, Graham transferred to the Florida Bible Institute in Temple Terrace, Florida.[25] While still a student, Graham preached his first sermon at Bostwick Baptist Church near Palatka, Florida.[26] In his autobiography, Graham wrote of receiving his “calling on the 18th green of the Temple Terrace Golf an Country Club”, which was adjacent to the institute’s campus. Reverend Billy Graham Memorial Park was later established on the Hillsborough River, directly east of the 18th green and across from where Graham often paddled a canoe to a small island in the river, where he would practice preaching to the birds, alligators, and cypress stumps. In 1939, Graham was ordained by a group of Southern Baptist clergy at Peniel Baptist Church in Palatka, Florida.[27] In 1940, he graduated from there with a Bachelor of Theology degree.[28][29]

Graham then enrolled in Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, and during his time at there he decided to accept the Bible as the infallible word of God. Henrietta Mears of the First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood in California was instrumental in helping Graham wrestle with the issue. He settled it at Forest Home Christian Camp (now called Forest Home Ministries) southeast of the Big Bear Lake area in southern California.[30][31] While attending Wheaton in 1941, Graham was invited to preach one Sunday at the United Gospel Tabernacle church. After that, the congregation repeatedly asked Graham preach at their church and later asked him to become the pastor of their church. After Graham prayed and sought advice from his friend, Dr. Edman, Graham become the pastor of their church.[32]

In June 1943, Graham graduated from Wheaton College[33] with a degree in anthropology.[34] That same year, Robert Van Kampen, treasurer of the National Gideon Association, invited Graham to preach at Western Springs Baptist Church, and Graham accepted the opportunity on the spot. While there, his friend Torrey Johnson, pastor of the Midwest Bible Church in Chicago, told Graham that his radio program, Songs in the Night, was about to be canceled due to lack of funding. Consulting with the members of his church in Western Springs, Graham decided to take over Johnson’s program with financial support from his congregation. Launching the new radio program on January 2, 1944, still called Songs in the Night, Graham recruited the bass-baritone George Beverly Shea as his director of radio ministry.

In 1948, in a hotel room in Modesto, California, Graham and his evangelistic team established the Modesto Manifesto, a code of ethics for life and work to protect against accusations of financial, sexual and power abuse.[35] This code includes rules for collecting offerings in churches, working only with churches supportive of cooperative evangelism, using official crowd estimates at outdoor events, and a commitment to never be alone with a woman other than his wife (which become known as the “Billy Graham rule”).[36][37]

Graham was 29 in 1948 when he became president of Northwestern Bible College in Minneapolis; he was the youngest president of a college or university in the country and held the position for four years before he resigned in 1952.[38] Graham initially intended to become a chaplain in the Armed Forces, but he contracted mumps shortly after applying for a commission. After a period of recuperation in Florida, he was hired as the first full-time evangelist of the new Youth for Christ (YFC), co-founded by Torrey Johnson and the Canadian evangelist Charles Templeton. Graham traveled throughout both the United States and Europe as a YFCI evangelist. Templeton applied to Princeton Theological Seminary for an advanced theological degree and urged Graham to do so as well, but he declined as he was already serving as the president of Northwestern Bible College.[39]

In 1949 Graham scheduled a series of revival meetings in Los Angeles, for which he erected circus tents in a parking lot.[10] He attracted national media coverage, especially in the conservative Hearst chain of newspapers, although Hearst and Graham never met.[40] The crusade event ran for eight weeks – five weeks longer than planned. Graham became a national figure with heavy coverage from the wire services and national magazines.[41] Pianist Rudy Atwood, who played for the tent meetings, wrote that they “rocketed Billy Graham into national prominence, and resulted in the conversion of a number of show-business personalities”.[42]

Crusades[edit source]

Main article: List of Billy Graham’s crusadesGraham speaking at a Crusade in Düsseldorf, Germany on June 21, 1954.

From the time his ministry began in 1947, Graham conducted more than 400 crusades in 185 countries and territories on six continents. The first Billy Graham Crusade, held September 13–21, 1947, in the Civic Auditorium in Grand Rapids, Michigan, was attended by 6,000 people. Graham was 28 years old. He called them crusades, after the medieval Christian forces who conquered Jerusalem.[citation needed] He would rent a large venue, such as a stadium, park, or street. As the sessions became larger, he arranged a group of up to 5,000 people to sing in a choir. He would preach the gospel and invite people to come forward (a practice begun by Dwight L. Moody). Such people were called inquirers and were given the chance to speak one-on-one with a counselor, to clarify questions and pray together. The inquirers were often given a copy of the Gospel of John or a Bible study booklet. In Durban, South Africa, in 1973, the crowd of some 100,000 was the first large mixed-race event in apartheid South Africa in which he stated that “apartheid is a sin.”[43][44] In Moscow, in 1992, one-quarter of the 155,000 people in Graham’s audience went forward at his call.[22] During his crusades, he frequently used the altar call song, “Just As I Am“.[45]

Graham was offered a five-year, $1 million contract from NBC to appear on television opposite Arthur Godfrey, but he had prearranged commitments. He turned down the offer in order to continue his touring revivals.[46] Graham had crusades in London, which lasted 12 weeks, and a New York City crusade in Madison Square Garden in 1957, which ran nightly for 16 weeks.

Student ministry[edit source]

Graham spoke at InterVarsity Christian Fellowship’s Urbana Student Missions Conference at least nine times – in 1948, 1957, 1961, 1964, 1976, 1979, 1981, 1984, and 1987.[47]

At each Urbana conference, he challenged the thousands of attendees to make a commitment to follow Jesus Christ for the rest of their lives. He often quoted a six-word phrase that was reportedly written in the Bible of William Whiting Borden, the son of a wealthy silver magnate: “No reserves, no retreat, no regrets”.[48] Borden had died in Egypt on his way to the mission field.[citation needed]

Graham also held evangelistic meetings on a number of college campuses: at the University of Minnesota during InterVarsity’s “Year of Evangelism” in 1950–51, a 4-day mission at Yale University in 1957, and a week-long series of meetings at the University of North Carolina’s Carmichael Auditorium in September 1982.[49]

In 1955, he was invited by Cambridge University students to lead the mission at the university; the mission was arranged by the Cambridge Inter-Collegiate Christian Union, with London pastor-theologian John Stott serving as Graham’s chief assistant. This invitation was greeted with much disapproval in the correspondence columns of The Times.[50]

Evangelistic association[edit source]

In 1950, Graham founded the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) with its headquarters in Minneapolis. The association relocated to Charlotte, North Carolina, in 1999, and maintains a number of international offices, such as in Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Buenos Aires.[43] BGEA ministries have included:

- Hour of Decision, a weekly radio program broadcast around the world for 66 years (1950-2016)[51]

- Mission television specials broadcast in almost every market in the US and Canada[citation needed]

- A syndicated newspaper column, My Answer, carried by newspapers across the United States and distributed by Tribune Content Agency[52]

- Decision magazine, the official publication of the association[53]

- Christianity Today was started in 1956 with Carl F. H. Henry as its first editor[citation needed]

- Passageway.org, the website for a youth discipleship program created by BGEA[citation needed]

- World Wide Pictures, which has produced and distributed more than 130 films[citation needed]

In April 2013, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association started “My Hope With Billy Graham”, the largest outreach in its history, encouraging church members to spread the gospel in small group meetings after showing a video message by Graham. “The idea is for Christians to follow the example of the disciple Matthew in the New Testament and spread the gospel in their own homes.”[54] The video, called “The Cross”, is the main program in the My Hope America series and was also broadcast the week of Graham’s 95th birthday.[55]

Civil rights movement[edit source]

Graham’s early crusades were segregated, but he began adjusting his approach in the 1950s.[56] During a 1953 rally in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Graham tore down the ropes that organizers had erected in order to segregate the audience into racial sections. In his memoirs, he recounted that he told two ushers to leave the barriers down “or you can go on and have the revival without me.”[57] He warned a white audience, “we have been proud and thought we were better than any other race, any other people. Ladies and gentlemen, we are going to stumble into hell because of our pride.”[57]

In 1957, Graham’s stance towards integration became more publicly shown when he allowed black ministers Thomas Kilgore and Gardner C. Taylor to serve as members of his New York Crusade’s executive committee[58] and invited Martin Luther King Jr., whom he first met during the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955,[58] to join him in the pulpit at his 16-week revival in New York City, where 2.3 million gathered at Madison Square Garden, Yankee Stadium, and Times Square to hear them.[10] Graham recalled in his autobiography that during this time, he and King developed a close friendship and that he was eventually one of the few people who referred to King as “Mike”, a nickname which King asked only his closest friends to call him.[59] Following King’s assassination in 1968, Graham mourned that the US had lost “a social leader and a prophet”.[58] In private, Graham advised King and other members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).[60]

Despite their friendship, tensions between Graham and King emerged in 1958 when the sponsoring committee of a crusade which took place in San Antonio, Texas on July 25 arranged for Graham to be introduced by that state’s segregationist governor, Price Daniel.[58] On July 23, King sent a letter to Graham and informed him that allowing Daniel to speak at a crusade which occurred the night before the state’s Democratic Primary “can well be interpreted as your endorsement of racial segregation and discrimination.”[61] Graham’s advisor, Grady Wilson, replied to King that “even though we do not see eye to eye with him on every issue, we still love him in Christ.”[62] Though Graham’s appearance with Daniel dashed King’s hopes of holding joint crusades with Graham in the Deep South,[60] the two still remained friends and King told a Canadian television audience the following year that Graham had taken a “very strong stance against segregation.”[60] Graham and King would also come to differ on the Vietnam War.[58] After King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech denouncing US intervention in Vietnam, Graham castigated him and others for their criticism of US foreign policy.[58]

By the middle of 1960, King and Graham traveled together to the Tenth Baptist World Congress of the Baptist World Alliance.[58] In 1963, Graham posted bail for King to be released from jail during the Birmingham campaign, according to Long (2008),[63] and the King Center acknowledged that Graham had bailed King out of jail during the Albany Movement,[64] although historian Steven Miller told CNN he could not find any proof of the incident.[65] Graham held integrated crusades in Birmingham, Alabama, on Easter 1964 in the aftermath of the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, and toured Alabama again in the wake of the violence that accompanied the first Selma to Montgomery march in 1965.[58]

Following Graham’s death, former SCLC official and future Atlanta politician Andrew Young, who spoke alongside Coretta Scott King at Graham’s 1994 crusade in Atlanta,[66] acknowledged his friendship with Graham and stated that Graham did in fact travel with King to the 1965 European Baptist Convention.[67] Young also claimed that Graham had often invited King to his crusades in the Northern states.[68] Former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) leader and future United States Congressman John Lewis also credited Graham as a major inspiration for his activism.[69] Lewis described Graham as a “Saint” and someone who “taught us how to live and who taught us how to die.”[69]

Graham’s faith prompted his maturing view of race and segregation; he told a member of the Ku Klux Klan that integration was necessary primarily for religious reasons: “There is no scriptural basis for segregation”, Graham argued. “The ground at the foot of the cross is level, and it touches my heart when I see whites standing shoulder to shoulder with blacks at the cross.”[70]

Lausanne Movement[edit source]

The friendship between Graham and John Stott led to a further partnership in the Lausanne Movement, of which Graham was a founder. It built on Graham’s 1966 World Congress on Evangelism in Berlin.[clarification needed] In collaboration with Christianity Today, Graham convened what Time magazine described as “a formidable forum, possibly the widest–ranging meeting of Christians ever held”[71] with 2,700 participants from 150 nations gathering for the International Congress on World Evangelization. Women were represented by Millie Dienert, who chaired the prayer committee.[72] This took place in Lausanne, Switzerland (July 16–25, 1974), and the movement which ensued took its name from the host city. Its purpose was to strengthen the global church for world evangelization, and to engage ideological and sociological trends which bore on this.[73] Graham invited Stott to be chief architect of the Lausanne Covenant, which issued from the Congress and which, according to Graham, “helped challenge and unite evangelical Christians in the great task of world evangelization.”[74] The movement remains a significant fruit of Graham’s legacy, with a presence in nearly every nation.[75]

Multiple roles[edit source]

Graham with his son, Franklin, at Cleveland Stadium, June 1994

Graham played multiple roles that reinforced each other. Grant Wacker identified eight major roles that he played: preacher, icon, Southerner, entrepreneur, architect (bridge builder), pilgrim, pastor and finally his widely recognized status as America’s Protestant patriarch, which was on a par with Martin Luther King and Pope John Paul II.[76]

Graham deliberately reached into the secular world as a bridge builder. For example, as an entrepreneur he built his own pavilion for the 1964 New York World’s Fair.[77] He appeared as a guest on a 1969 Woody Allen television special, where he joined the comedian in a witty exchange on theological matters.[78] During the Cold War, Graham-the-bridge-builder became the first evangelist of note to speak behind the Iron Curtain, addressing large crowds in countries throughout Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union, calling for peace.[79] During the apartheid era, Graham consistently refused to visit South Africa until its government allowed integrated seating for audiences. During his first crusade there in 1973, he openly denounced apartheid.[80] Graham also corresponded with imprisoned South African leader Nelson Mandela during the latter’s 27-year imprisonment.[81]

Graham at the Feyenoord-stadion in Rotterdam, the Netherlands (June 30, 1955)

In 1984, he led a series of summer meetings—Mission England—in the United Kingdom, and he used outdoor football (soccer) fields for his venues.

Graham was interested in fostering evangelism around the world. In 1983, 1986 and 2000 he sponsored, organized and paid for massive training conferences for Christian evangelists; this was the largest representation of nations ever held until that time. Over 157 nations were gathered in 2000 at the RAI Convention Center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. At one revival in Seoul, South Korea, Graham attracted more than one million people to a single service.[46] He appeared in China in 1988 – for Ruth, this was a homecoming, since she had been born in China to missionary parents. He appeared in North Korea in 1992.[70]

On October 15, 1989, Graham received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. He was the only person functioning as a minister who received a star in that capacity.[82]

On September 22, 1991, Graham held his largest event in North America on the Great Lawn of Manhattan’s Central Park. City officials estimated that more than 250,000 were in attendance. In 1998, Graham spoke to a crowd of scientists and philosophers at the Technology, Entertainment, Design Conference.

On September 14, 2001 (only three days after the World Trade Center attacks), Graham was invited to lead a service at Washington National Cathedral; the service was attended by President George W. Bush and past and present leaders. He also spoke at the memorial service following the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995.[70] On June 24–26, 2005, Graham began what he said would be his last North American crusade, three days at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in the borough of Queens, New York City. On the weekend of March 11–12, 2006, Graham held the “Festival of Hope” with his son, Franklin Graham. The festival was held in New Orleans, which was recovering from Hurricane Katrina.

Graham prepared one last sermon, “My Hope America”, which was released on DVD and played around America and possibly worldwide between November 7–10, 2013. November 7 was Graham’s 95th birthday, and he hoped to cause a revival.[83]

Later life[edit source]

Graham said that his planned retirement was a result of his failing health; he had suffered from hydrocephalus from 1992 on.[84] In August 2005, Graham appeared at the groundbreaking for his library in Charlotte, North Carolina. Then 86, he used a walker during the ceremony. On July 9, 2006, he spoke at the Metro Maryland Franklin Graham Festival, held in Baltimore, Maryland, at Oriole Park at Camden Yards.

In April 2010, Graham was 91 and experiencing substantial vision, hearing and balance loss when he made a rare public appearance at the re-dedication of the renovated Billy Graham Library.[85]

There had been controversy over Graham’s proposed burial place; he announced in June 2007 that he and his wife would be buried alongside each other at the Billy Graham Library in his hometown of Charlotte. Graham’s younger son Ned had argued with older son Franklin about whether burial at a library would be appropriate. Ruth Graham had said that she wanted to be buried not in Charlotte but in the mountains at the Billy Graham Training Center at The Cove near Asheville, North Carolina, where she had lived for many years; Ned supported his mother’s choice.[86][87] Novelist Patricia Cornwell, a family friend, also opposed burial at the library, calling it a tourist attraction. Franklin wanted his parents to be buried at the library site.[86] At the time of Ruth Graham’s death, it was announced that they would be buried at the library site.[87]

Politics[edit source]

After his close relationships with Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon, Graham tried to avoid explicit partisanship. Bailey says: “He declined to sign or endorse political statements, and he distanced himself from the Christian right … His early years of fierce opposition to communism gave way to pleas for military disarmament and attention to AIDS, poverty and environmental threats.”[88]

Graham was a lifelong registered member of the Democratic Party.[89] In 1960, he was opposed to the candidacy of John F. Kennedy, fearing that Kennedy, as a Catholic, would be bound to follow the Pope. Graham worked “behind the scenes” to encourage influential Protestant ministers to speak out against Kennedy.[90] During the 1960 campaign, Graham met with a conference of Protestant ministers in Montreux, Switzerland, to discuss their mobilization of congregations to defeat Kennedy.[91] According to the PBS Frontline program, God in America (2010), Episode 5, in September 1960, Graham organized a meeting of hundreds of Protestant ministers in Washington, D.C. for this purpose; the meeting was led by Norman Vincent Peale.[90] This was shortly before Kennedy’s speech in Houston, Texas on the separation of church and state; the speech was considered to be successful in meeting the concerns of many voters. After his election, however, Kennedy invited Graham to play golf in Palm Beach, Florida, after which Graham acknowledged Kennedy’s election as an opportunity for Catholics and Protestants to come closer together.[92][93] After they had discussed Jesus Christ at that meeting, the two remained in touch, meeting for the last time at a National Day of Prayer meeting in February 1963.[93] In his autobiography, Graham claimed to have felt an “inner foreboding” in the week before Kennedy’s assassination, and to have tried to contact him to say, “Don’t go to Texas!”[94]

Graham opposed the large majority of abortions, but supported it as a legal option in a very narrow range of circumstances: rape, incest, and the life of the mother.[95] The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association states that “Life is sacred, and we must seek to protect all human life: the unborn, the child, the adult, and the aged.”[96]

Graham leaned toward the Republicans during the presidency of Richard Nixon, whom he had met and befriended as vice president under Dwight D. Eisenhower.[97] He did not completely ally himself with the later religious right, saying that Jesus did not have a political party.[22] He gave his support to various political candidates over the years.[97]

In 2007, Graham explained his refusal to join Jerry Falwell‘s Moral Majority in 1979, saying: “I’m for morality, but morality goes beyond sex to human freedom and social justice. We as clergy know so very little to speak with authority on the Panama Canal or superiority of armaments. Evangelists cannot be closely identified with any particular party or person. We have to stand in the middle in order to preach to all people, right and left. I haven’t been faithful to my own advice in the past. I will be in the future.”[98]

According to a 2006 Newsweek interview, “For Graham, politics is a secondary to the Gospel … When Newsweek asked Graham whether ministers – whether they think of themselves as evangelists, pastors or a bit of both – should spend time engaged with politics, he replied: ‘You know, I think in a way that has to be up to the individual as he feels led of the Lord. A lot of things that I commented on years ago would not have been of the Lord, I’m sure, but I think you have some – like communism, or segregation, on which I think you have a responsibility to speak out.’”[99]

In 2012, Graham endorsed the Republican presidential candidate, Mitt Romney.[100] Shortly after, apparently in order to accommodate Romney, who is a Mormon, references to Mormonism as a religious cult (“A cult is any group which teaches doctrines or beliefs that deviate from the biblical message of the Christian faith.”) were removed from Graham’s website.[101][102] Observers have questioned whether the support of Republican and religious right politics on issues such as same-sex marriage coming from Graham – who stopped speaking in public or to reporters – in fact reflects the views of his son, Franklin, head of the BGEA. Franklin denied this, and said that he would continue to act as his father’s spokesperson rather than allowing press conferences.[103] In 2016, according to his son Franklin, Graham voted for Donald Trump.[104]

Pastor to presidents[edit source]

President Ronald Reagan and first lady Nancy Reagan greet Graham at the National Prayer Breakfast of 1981

Graham had a personal audience with many sitting US presidents, from Harry S. Truman to Barack Obama – 12 consecutive presidents. After meeting with Truman in 1950, Graham told the press he had urged the president to counter communism in North Korea. Truman disliked him and did not speak with him for years after that meeting.[22] Later he always treated his conversations with presidents as confidential.[97]

Truman was not fond of Graham. He wrote about Graham in his 1974 autobiography Plain Speaking, “But now we’ve got just this one evangelist, this Billy Graham, and he’s gone off the beam. He’s … well, I hadn’t ought to say this, but he’s one of those counterfeits I was telling you about. He claims he’s a friend of all the presidents, but he was never a friend of mine when I was President. I just don’t go for people like that. All he’s interested in is getting his name in the paper.”[105]Graham in 1966

Graham became a regular visitor during the tenure of Dwight D. Eisenhower. He purportedly urged him to intervene with federal troops in the case of the Little Rock Nine to gain admission of black students to public schools.[22] House Speaker Sam Rayburn convinced Congress to allow Graham to conduct the first religious service on the steps of the Capitol building in 1952.[22][106] Eisenhower asked for Graham while on his deathbed.[107]

Graham met and would become a close friend of Vice President Richard Nixon,[97][108] and supported Nixon, a Quaker, for the 1960 presidential election.[22] He convened an August strategy session of evangelical leaders in Montreaux, Switzerland, to plan how best to oppose Nixon’s Roman Catholic opponent, Senator John F. Kennedy.[109] Though a registered Democrat, Graham also maintained firm support of aggression against the foreign threat of Communism and strongly sympathized with Nixon’s views regarding American foreign policy.[110] Thus, he was more sympathetic to Republican administrations.[97][111]

On December 16, 1963, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, who was impressed by the way Graham had praised the work of his great-grandfather, George Washington Baines, invited Graham to the White House to give him spiritual counseling. After this visit, Johnson would frequently call on Graham for more spiritual counseling as well as companionship. As Graham recalled to his biographer Frady, “I almost used the White House as a hotel when Johnson was President. He was always trying to keep me there. He just never wanted me to leave.”[60]

In contrast with his more limited access with Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy, Graham would not only visit the White House private quarters but would also at times kneel at Johnson’s bedside and then pray with him whenever the President requested him to do so. Graham once recalled “I have never had many people do that.”[60] In addition to his White House visits, Graham would visit Johnson at Camp David and occasionally met with the President when he retreated to his private ranch in Stonewall, Texas. Johnson was also the first sitting president to attend one of Graham’s crusades, which took place in Houston, Texas, in 1965.[60]

During the 1964 United States presidential election, supporters of Republican nominee Barry Goldwater sent an estimated 2 million telegrams to Graham’s hometown of Montreat, North Carolina, and sought the preacher’s endorsement. Supportive of Johnson’s domestic policies, and hoping to preserve his friendship with the President, Graham resisted pressure to endorse Goldwater and stayed neutral in the election. Following Johnson’s election victory, Graham’s role as the main White House pastor was solidified. At one point, Johnson even considered making Graham a member of his cabinet and grooming him to be his successor, though Graham insisted he had no political ambitions and wished to remain a preacher.[60] Graham’s biographer David Aikman acknowledged that the preacher was closer to Johnson than any other President he had ever known.[110]

He spent the last night of Johnson’s presidency in the White House, and he stayed for the first night of Nixon’s.[107] After Nixon’s victorious 1968 presidential campaign, Graham became an adviser, regularly visiting the White House and leading the president’s private worship services.[97] In a meeting they had with Golda Meir, Nixon offered Graham the ambassadorship to Israel, but he refused.[22]President Barack Obama and Graham meet at Graham’s home in Montreat, North Carolina, April 2010

In 1970, Nixon appeared at a Graham revival in East Tennessee, which they thought safe politically. It drew one of the largest crowds in Tennessee of protesters against the Vietnam War. Nixon was the first president to give a speech from an evangelist’s platform.[97] Their friendship became strained in 1973 when Graham rebuked Nixon for his post-Watergate behavior and the profanity heard on the Watergate tapes.[112] They eventually reconciled after Nixon’s resignation.[97]

Graham officiated at one presidential burial and one presidential funeral. He presided over the graveside services of President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1973 and took part in eulogizing the former president. Graham officiated at the funeral services of former First Lady Pat Nixon in 1993,[22] and the death and state funeral of Richard Nixon in 1994.[113] During the Monica Lewinsky scandal, Graham asserted that he believed President Bill Clinton to be “a spiritual person”.[citation needed] He was unable to attend the state funeral of Ronald Reagan on June 11, 2004, as he was recovering from hip replacement surgery.[114] This was mentioned by George W. Bush in his eulogy.

On April 25, 2010, President Barack Obama visited Graham at his home in Montreat, North Carolina, where they “had a private prayer”.[115]

Relationship with Queen Elizabeth II[edit source]

Graham had a friendly relationship with Queen Elizabeth II and was frequently invited by the Royal Family to special events.[116][117] They first met in 1955 and Graham preached at Windsor Chapel at the Queen’s invitation during the following year. Their friendly relationship may have been because they shared a traditional approach to the practical aspects of the Christian faith.[118]

Foreign policy views[edit source]

Graham was outspoken against communism and supported the American Cold War policy, including the Vietnam War. In a secret letter from April 15, 1969, made public twenty years later, Graham encouraged Nixon to bomb the dikes in North Vietnam if the peace talks in Paris should fail. This action would “destroy the economy of North Vietnam” and, by Nixon’s estimate, would have killed a million people.[119]

In 1982, Graham preached in the Soviet Union and attended a wreath-laying ceremony to honor the war dead of World War II, when the Soviets were American allies in the fight against Nazism. He voiced fear of a second holocaust, not against Jews, but “a nuclear holocaust” and advised that “our greatest contribution to world peace is to live with Christ every day.”[120]

In a 1999 speech, Graham discussed his relationship with the late North Korean leader Kim Il-sung, praising him as a “different kind of communist” and “one of the great fighters for freedom in his country against the Japanese.” Graham went on to note that although he had never met Kim’s son and former North Korean leader Kim Jong-il, he had “exchanged gifts with him.”[121]

Controversial views[edit source]

Discussion of Jews with President Nixon[edit source]

During the Watergate affair, there were suggestions that Graham had agreed with many of President Richard Nixon‘s antisemitic opinions, but he denied them and stressed his efforts to build bridges to the Jewish community. In 2002, the controversy was renewed when declassified “Richard Nixon tapes” confirmed remarks made by Graham to Nixon three decades earlier.[122] Captured on the tapes, Graham agreed with Nixon that Jews control the American media, calling it a “stranglehold” during a 1972 conversation with Nixon, and suggesting that if Nixon was re-elected that they might be able to do something about it.[123]

When the tapes were made public, Graham apologized[124][125] and said, “Although I have no memory of the occasion, I deeply regret comments I apparently made in an Oval Office conversation with President Nixon … some 30 years ago. … They do not reflect my views and I sincerely apologize for any offense caused by the remarks.”[126] According to Newsweek magazine, “[T]he shock of the revelation was magnified because of Graham’s longtime support of Israel and his refusal to join in calls for conversion of the Jews.”[125]

In 2009, more Nixon tapes were released, in which Graham is heard in a 1973 conversation with Nixon referring to a group of Jewish journalists and “the synagogue of Satan“. A spokesman for Graham said that Graham has never been an antisemite and that the comparison (in accord with the context of the quotation in the Book of Revelation[127]) was directed specifically at those claiming to be Jews, but not holding to traditional Jewish values.[128]

Ecumenism[edit source]

After a 1957 crusade in New York, some more fundamentalist Protestant Christians criticized Graham for his ecumenism, even calling him “Antichrist“.[129]

Graham expressed inclusivist views, suggesting that people without explicit faith in Jesus can be saved. In a 1997 interview with Robert Schuller, Graham said

I think that everybody that loves or knows Christ, whether they are conscious of it or not, they are members of the body of Christ … [God] is calling people out of the world for his name, whether they come from the Muslim world, or the Buddhist world or the non-believing world, they are members of the Body of Christ because they have been called by God. They may not know the name of Jesus but they know in their hearts that they need something they do not have, and they turn to the only light they have, and I think that they are saved and they are going to be with us in heaven.[130]

Iain Murray, writing from a conservative Protestant standpoint, argues that “Graham’s concessions are sad words from one who once spoke on the basis of biblical certainties.”[131]Further information: Anonymous Christian

Views on women[edit source]

In 1970, Graham stated that feminism was “an echo of our overall philosophy of permissiveness” and that women did not want to be “competitive juggernauts pitted against male chauvinists”.[132][133] He further stated that the role of wife, mother, and homemaker was the destiny of “real womanhood” according to the Judeo-Christian ethic. Graham’s assertions, published in the Ladies’ Home Journal, elicited letters of protest, and were offered as rebuttal to the establishment of “The New Feminism” section of the publication added following a sit-in protest at the Journal offices demanding female representation on the staff of the publication.[134][135][136][137]

Graham’s daughter Bunny recounted her father denying her and her sisters higher education. As reported in The Washington Post:[138]

Bunny remembers being groomed for the life of wife, homemaker, and mother. “There was never an idea of a career for us”, she said. “I wanted to go to nursing school – Wheaton had a five-year program – but Daddy said no. No reason, no explanation, just ‘No.’ It wasn’t confrontational and he wasn’t angry, but when he decided, that was the end of it.” She added, “He has forgotten that. Mother has not.”

Nevertheless, Graham’s daughter Anne has long been an active Christian minister who leads a Christian ministry organization known as AnGeL Ministries.[139] Anne’s website even claims that her father called her “the best preacher in the family”.[139]

Graham talked his future wife, Ruth, into abandoning her ambition to evangelize in Tibet in favor of staying in the United States to marry him – and that to do otherwise would be “to thwart God’s obvious will”.[138] After Ruth agreed to marry him, Graham cited the Bible for claiming authority over her, saying, “then I’ll do the leading and you do the following”.[138] Despite Graham’s public views on womanhood, it has been acknowledged that Ruth still remained active in Christian ministry after they married, often teaching Sunday School.[140] In addition to his two sons, all three of Graham’s daughters would become Christian ministers as well.[141]

Views on homosexuality[edit source]

Graham regarded homosexuality as a sin, and in 1974 described it as “a sinister form of perversion”.[142][143] In 1993 he said that he thought AIDS might be a “judgment” from God, but two weeks later he retracted the remark, saying, “I don’t believe that, and I don’t know why I said it.”[144] Graham opposed same-sex marriage,[145] and in 2012 he took out full-page ads in favor of North Carolina Amendment 1 which banned it in North Carolina.[146][147] Graham’s stated position was that he did not want to talk about homosexuality as a political issue.[144] Corky Siemaszko, writing for NBC News, noted that after the 1993 incident, Graham “largely steered clear of the subject”.[148] However, Graham appeared to take a more tolerant approach to the issue of homosexuality when he appeared on the May 2, 1997, episode of 20/20, stating “I think that the Bible teaches that homosexuality is a sin, but the Bible also teaches that pride is a sin, jealously is a sin, and hate is a sin, evil thoughts are a sin, and so I don’t think that homosexuality should be chosen as the overwhelming sin that we are doing today.”[149] After his death, commentators, such as Douglas Robertson writing for The Independent, called Graham “homophobic“.[150]

Awards and honors[edit source]

Graham was frequently honored by surveys, including “Greatest Living American” and consistently ranked among the most admired persons in the United States and the world.[46] He appeared most frequently on Gallup‘s list of most admired people.[151] On the day of his death, Graham had been on Gallup’s Top 10 “Most Admired Man” list 61 times, and held the highest rank of any person since the list began in 1948.[14]

In 1967, he was the first Protestant to receive an honorary degree from Belmont Abbey College, a Roman Catholic school.[152]

In 1983, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by US President Ronald Reagan.[153]

Graham received the Big Brother of the Year Award for his work on behalf of children. He was cited by the George Washington Carver Memorial Institute for his contributions to race relations. He received the Templeton Foundation Prize for Progress in Religion and the Sylvanus Thayer Award for his commitment to “Duty, Honor, Country”. The “Billy Graham Children’s Health Center” in Asheville is named after and funded by Graham.[154]

In 1999, the Gospel Music Association inducted Graham into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame to recognize his contributions to Christian music artists such as Michael W. Smith, dc Talk, Amy Grant, Jars of Clay and others who performed at the Billy Graham Crusades.[155] Graham was the first non-musician inducted,[156] and had also helped to revitalize interest in hymns and create new favorite songs.[157] Singer Michael W. Smith was active in Billy Graham Crusades as well as Samaritan’s Purse.[158] Smith sang “Just As I Am” in a tribute to Graham at the 44th GMA Dove Awards.[159] He also sang it at the memorial service honoring Graham at the United States Capitol rotunda on February 28, 2018.[160][161]

In 2000, former First Lady Nancy Reagan presented the Ronald Reagan Freedom Award to Graham. Graham was a friend of the Reagans for years.[162]

In 2001, Queen Elizabeth II awarded him an honorary knighthood. The honor was presented to him by Sir Christopher Meyer, British Ambassador to the US at the British Embassy in Washington DC on December 6, 2001.[163]

A professorial chair is named after him at the Alabama Baptist-affiliated Samford University, the Billy Graham Professor of Evangelism and Church Growth.[122] His alma mater, Wheaton College, has an archive of his papers at the Billy Graham Center.[10] The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has the Billy Graham School of Missions, Evangelism and Ministry. Graham received 20 honorary degrees and refused at least that many more.[46] In San Francisco, California, the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium is sometimes erroneously called the “Billy Graham Civic Auditorium” and incorrectly considered to be named in his honor, but it is actually named after the rock and roll promoter Bill Graham.[164]

On May 31, 2007, the $27 million Billy Graham Library was officially dedicated in Charlotte. Former presidents Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, and Bill Clinton appeared to celebrate with Graham.[165] A highway in Charlotte bears Graham’s name,[86] as does I-240 near Graham’s home in Asheville.

As Graham’s final crusade approached in 2005, his friend Pat Boone chose to create a song in honor of Graham,[166] which he co-wrote and produced with David Pack and Billy Dean,[167] who digitally combined studio recordings of various artists into what has been called a “‘We Are the World‘-type” production.[168] Named “Thank You Billy Graham”, the song’s video[169] was introduced by Bono,[168] and included Faith Hill, MxPx,[166] John Ford Coley, John Elefante, Mike Herrera, Michael McDonald, Jeffrey Osborne, LeAnn Rimes, Kenny Rogers, Connie Smith, Michael Tait and other singers, with brief narration by Larry King,[170] and was directed by Brian Lockwood[171] as a tribute album.[172] In 2013, the album My Hope: Songs Inspired by the Message and Mission of Billy Graham was recorded by Amy Grant, Kari Jobe, Newsboys, Matthew West, tobyMac and other music artists with new songs to honor Graham during his My Hope America with Billy Graham outreach and the publication of his book The Reason for My Hope: Salvation.[173] Other songs written to honor Graham include “Hero of the Faith” written by Eddie Carswell of NewSong, which became a hit,[174] “Billy, You’re My Hero” by Greg Hitchcock,[175] “Billy Graham” by The Swirling Eddies, “Billy Graham’s Bible” by Joe Nichols, “Billy Frank” by Randy Stonehill, and an original song titled “Just as I Am” by Fernando Ortega.[166]

The movie Billy: The Early Years officially premiered in theaters on October 10, 2008, less than one month before Graham’s 90th birthday.[176] Graham did not comment on the film, but his son Franklin released a critical statement on August 18, 2008, noting that the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association “has not collaborated with nor does it endorse the movie”.[177] Graham’s eldest daughter, Gigi, praised the film and was hired as a consultant to help promote it.[178]

Other honors[edit source]

1996 Congressional Gold Medal shows Ruth and Billy Graham in profile (obverse); the Ruth and Billy Graham Children’s Health Center in Asheville, North Carolina (reverse).

- The Salvation Army‘s Distinguished Service Medal[179]

- Who’s Who in America listing annually since 1954[180]

- Freedoms Foundation Distinguished Persons Award (several years)[181][182]

- Gold Medal Award, National Institute of Social Science, New York, 1957[182]

- Annual Gutenberg Award of the Chicago Bible Society, 1962[183]

- Gold Award of the George Washington Carver Memorial Institute, 1964, for contribution to race relations, presented by Senator Javits (NY)[184]

- Speaker of the Year Award, awarded by Delta Sigma Rho-Tau Kappa Alpha, 1965[185]

- The American Academy of Achievement‘s Golden Plate Award, 1965[186]

- Horatio Alger Award, 1965[184]

- National Citizenship Award by the Military Chaplains Association of the United States of America, 1965[179]

- Wisdom Award of Honor, 1965[187]

- The Torch of Liberty Plaque by the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, 1969[185]

- George Washington Honor Medal from Freedoms Foundation of Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, for his sermon “The Violent Society”, 1969 (also in 1974)[179]

- Honored by Morality in Media for “fostering the principles of truth, taste, inspiration and love in media”, 1969[179]

- International Brotherhood Award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews, 1971[188]

- Distinguished Service Award from the National Association of Broadcasters, 1972[189]

- Franciscan International Award, 1972[184]

- Sylvanus Thayer Award from United States Military Academy Association of Graduates at West Point (The most prestigious award the United States Military Academy gives to a US citizen), 1972[182]

- Direct Selling Association‘s Salesman of the Decade award, 1975[185]

- Philip Award from the Association of United Methodist Evangelists, 1976[190]

- American Jewish Committee‘s First National Interreligious Award, 1977[191]

- Southern Baptist Radio and Television Commission‘s Distinguished Communications Medal, 1977[179]

- Jabotinsky Centennial Medal presented by The Jabotinsky Foundation, 1980[182]

- Religious Broadcasting Hall of Fame award, 1981[192]

- Templeton Foundation Prize for Progress in Religion award, 1982[184]

- Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award, 1983[192]

- National Religious Broadcasters Award of Merit, 1986[192]

- North Carolina Award in Public Service, 1986[193]

- Good Housekeeping Most Admired Men Poll,[193] 1997, No. 1 for five years in a row and 16th time in top 10[180]

- Congressional Gold Medal (along with wife Ruth), highest honor Congress can bestow on a private citizen, 1996[194]

- Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation Freedom Award, for monumental and lasting contributions to the cause of freedom, 2000[195]

- Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE)[192] for his international contribution to civic and religious life over 60 years, 2001[196]

- Many honorary degrees including University of Northwestern – St. Paul, Minnesota, where Graham was once president, named its newest campus building the Billy Graham Community Life Commons.[197] He also received honorary Doctor of Divinity degrees.[198][199]

Media portrayals[edit source]

- Unbroken: Path to Redemption (2018): Played by his grandson Will Graham.

- The Crown (2016 – present): Netflix series, Season 2 Episode 6. Played by actor Paul Sparks.[200]

- Billy: The Early Years (2008): Played by actor Armie Hammer.[201]

- Man in the 5th Dimension (1964): short biographical film featuring Graham.

Works[edit source]

Graham’s My Answer advice column appeared in newspapers for more than 60 years as of 2017.[202]

Books[edit source]

Graham authored the following books;[203] many of which have become bestsellers. In the 1970s, for instance, The Jesus Generation sold 200,000 copies in the first two weeks after its publication; Angels: God’s Secret Agents had sales of a million copies within 90 days after release; How to Be Born Again was said to have made publishing history with its first printing of 800,000 copies.”[46]

- Calling Youth to Christ (1947)

- America’s Hour of Decision (1951)

- I Saw Your Sons at War (1953)

- Peace with God (1953, 1984)

- Freedom from the Seven Deadly Sins (1955)

- The Secret of Happiness (1955, 1985)

- Billy Graham Talks to Teenagers (1958)

- My Answer (1960)

- Billy Graham Answers Your Questions (1960)

- World Aflame (1965)

- The Challenge (1969)

- The Jesus Generation (1971)

- Angels: God’s Secret Agents (1975, 1985)

- How to Be Born Again (1977)

- The Holy Spirit (1978)

- Evangelist to the World (1979)

- Till Armageddon (1981)

- Approaching Hoofbeats (1983)

- A Biblical Standard for Evangelists (1984)

- Unto the Hills (1986)

- Facing Death and the Life After (1987)

- Answers to Life’s Problems (1988)

- Hope for the Troubled Heart (1991)

- Storm Warning (1992)

- Just As I Am: The Autobiography of Billy Graham (1997, 2007)

- Hope for Each Day (2002)

- The Key to Personal Peace (2003)

- Living in God’s Love: The New York Crusade (2005)

- The Journey: How to Live by Faith in an Uncertain World (2006)

- Wisdom for Each Day (2008)

- Nearing Home: Life, Faith, and Finishing Well (2011)

- The Heaven Answer Book (2012)

- The Reason for My Hope: Salvation (2013)[204]

- Where I Am: Heaven, Eternity, and Our Life Beyond the Now (2015)[205]

Personal life[edit source]

On August 13, 1943, Graham married Wheaton classmate Ruth Bell, whose parents were Presbyterian missionaries in China.[206] Her father, L. Nelson Bell, was a general surgeon.[46] Ruth died on June 14, 2007, at the age of 87.[207] The couple were married for almost 64 years.[208]Billy Graham and his wife in Oslo, Norway, 1955.

Graham and his wife had five children together.[209] Virginia Leftwich (Gigi) Graham (b. 1945), an inspirational speaker and author; Anne Graham Lotz (b. 1948), runs AnGeL ministries; Ruth Graham (b. 1950), founder and president of Ruth Graham & Friends, leads conferences throughout the US and Canada; Franklin Graham (b. 1952), serves as president and CEO of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association and as president and CEO of international relief organization, Samaritan’s Purse; and Nelson Edman Graham (b. 1958), a pastor who runs East Gates Ministries International,[210] which distributes Christian literature in China.

At the time of his death at age 99 in 2018, Graham was survived by 5 children, 19 grandchildren (including Will Graham and Tullian Tchividjian), 41 great-grandchildren and 6 great-great-grandchildren.[211]

Death[edit source]

Ceremony to the Reverend Billy Graham at the Capitol Rotunda, February 28, 2018.

Graham died of natural causes on February 21, 2018, at his home in Montreat, North Carolina, at the age of 99.[212][213]

External video  Capitol Visitation for Billy Graham, February 28, 2018, C-SPAN

Capitol Visitation for Billy Graham, February 28, 2018, C-SPAN Funeral Service, Billy Graham Library, Charlotte, North Carolina, March 2, 2018, C-SPAN

Funeral Service, Billy Graham Library, Charlotte, North Carolina, March 2, 2018, C-SPANOn February 28 and March 1, 2018, Graham became the fourth private citizen in United States history to lie in honor at the United States Capitol rotunda in Washington, D.C.[214][215] He is the first religious leader to be so honored. At the ceremony, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Speaker of the House Paul Ryan called Graham “America’s pastor”. President Donald Trump said Graham was “an ambassador for Christ”.[161] In addition, Televangelist Jim Bakker paid respect to Graham, stating he was the greatest preacher since Jesus. He also said that Graham visited him in prison.[216][217]

A private funeral service was held on March 2, 2018. Graham was buried beside his wife at the foot of the cross-shaped brick walkway in the Prayer Garden on the northeast side of the Billy Graham Library.[218] Graham’s pine plywood casket, handcrafted in 2006 by convicted murderers at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, is topped with a wooden cross nailed to it by the prisoners.[219][220]

He is honored with a commemoration on the liturgical calendar of the Anglican Church in North America on February 21.[221]

References[edit source]

- ^ “Indepth: Billy Graham”. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on January 19, 2011. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ Billy Graham: American Pilgrim. Oxford University Press. June 26, 2017. ISBN 9780190683528. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

Billy Graham stands among the most influential Christian leaders of the twentieth century.

- ^ Swank jr, J. Grant. “Billy Graham Classics Span 25 Years of Gospel Preaching for the Masses”. TBN. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ Ellis, Carl. “Preaching Redemption Amidst Racism: Remembering Billy Graham”. Christianity Today. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ^ “Media: Bios – William (Billy) F. Graham”. Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. Archived from the original on January 31, 2007.

- ^ “Billy Graham: Pastor to Presidents”. Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ Aikman 2010, p. 203.

- ^ “The Transition; Billy Graham to lead Prayers”. The New York Times. December 9, 1992. Retrieved December 24, 2007.

- ^ “Dr. Robert H. Schuller”. Crystal Cathedral Ministries. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Horstmann, Barry M. (June 27, 2002). “Man with a mission”. Cincinnati Post. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ Killen, Patricia O’Connell; Silk, Mark. Religion and Public Life in the Pacific Northwest: The None Zone. Rowman Altamira. p. 84.

In the 1957 revival in New York City Graham partnered with mainline Protestant denominations and insisted that those who were converted at the revivals return to their mainline churches.

- ^ Wacker, Grant (November 15, 2003). “The Billy pulpit: Graham’s career in the mainline”. The Christian Century. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

Crusade counselors are instructed to return the favor by sending “inquirers” back to mainline churches when requested.

- ^ Sweeney, Jon M. (February 21, 2018). “How Billy Graham shaped American Catholicism”. America. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

A few years later, in 1964, Cardinal Richard Cushing of Boston (who, as archbishop, had even endorsed a Graham crusade in Boston in 1950) met with Mr. Graham upon returning from Rome and the Second Vatican Council, declaring before a national television audience that Mr. Graham’s message was good for Catholics.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Newport, Frank. “In the News: Billy Graham on ‘Most Admired’ List 61 Times”. Gallup. February 21, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ Wacker 2014, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Bruns, Roger (2004). “A Farm Boy Becomes a Preacher”. Billy Graham: A Biography. Greenwood biographies. Greenwood Press. pp. 5–14. ISBN 978-0-313-32718-6.

- ^ “Billy Graham’s Mother Dies”. The New York Times Archives. August 16, 1981.

- ^ “Billy Graham’s Childhood Home”. Billygrahamlibrary.org. September 22, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ David George Mullan, Narratives of the Religious Self in Early-Modern Scotland, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2010, p. 27

- ^ “They Call Me Mother Graham Morrow Coffey Graham”. ccel.us. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ “Billy Graham Trivia What Did Billy Graham Read as a Child”. billygraham.org. August 10, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l Gibbs, Nancy; Ostling, Richard N. (November 15, 1993). “God’s Billy Pulpit”. Time. Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ “Who led Billy Graham to Christ…” Archives, Billy Graham Center, Wheaton College. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ “An Interview with Reverend Billy Graham”. The Charlotte Mecklenburg Story. Charlotte Mecklenburg Library. Archived from the original on October 21, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ The institute is now Trinity College of Florida in New Port Richey, Florida

- ^ Kirkland, Gary (June 25, 2005). “Graham’s first-ever sermon? Near Palatka”. Gainesville Sun. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ “Profile: William (Billy) F. Graham, Jr., Evangelist and Chairman of the Board”. billygraham.org/. Charlotte, NC: Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ^ Bill Adler, Ask Billy Graham: The World’s Best-Loved Preacher Answers Your Most Important Questions, Thomas Nelson Inc, USA, 2010, p. VIII

- ^ Beau Zimmer, Rev. Billy Graham attended Bible College in Temple Terrace, wtsp.com, USA, February 21, 2018

- ^ “Billy Graham’s California Dream”. californiality.com. Retrieved August 14, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ “The Tree Stump Prayer: When Billy Graham Overcame Doubt”. Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

- ^ Whalin, Terry (2014). Billy Graham A Biography of America’s Greatest Evangelist. Morgan James Publishing. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9781630472313.

- ^ Laurie, Greg (2021). Billy Graham The Man I Knew. Salem Books. pp. 115–117. ISBN 9781684510597.

- ^ “Wheaton College Alumnus Billy Graham: 1918-2018”. Wheaton.edu. February 21, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ Seth Dowland, The “Modesto Manifesto”, christianhistoryinstitute.org, USA, #111, 2014

- ^ Taylor, Justin (March 20, 2017). “Where Did the ‘Billy Graham Rule’ Come From?”. The Gospel Coalition. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ Yonat Shimron, Billy Graham made sure his integrity was never in question, religionnews.com, USA, February 23, 2018

- ^ AP and Hauser, Tom. “Evangelist Billy Graham, a former Minnesota College president, dies at 99”. Archived March 2, 2018, at the Wayback Machine ABC Eyewitness News. February 22, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ Farewell to God: My Reasons for Rejecting the Christian Faith.[page needed]

- ^ King, Randall E. (1997). “When Worlds Collide: Politics, Religion, and Media at the 1970 East Tennessee Billy Graham Crusade”. Journal of Church and State. 39 (2): 273–95. doi:10.1093/jcs/39.2.273. JSTOR 23919865.

- ^ William Martin, “The Riptide of Revival”, Christian History and Biography (2006), Issue 92, pp. 24–29, online

- ^ Atwood, Rudy (1970). The Rudy Atwood Story. Old Tappan, New Jersey: Revell. p. 113. OCLC 90745.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Stanley, Brian (March 2, 2018). “Billy Graham (1918–2018): Prophet of World Christianity?”. Centre for the Study of World Christianity. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ “AUDIO: Billy Graham Confronts Racism, Teaches God Loves Everyone”. Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ Usborne, David (June 24, 2005). “Billy Graham and the Last Crusade”. The Independent.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Stoddard, Maynard Good (March 1, 1986). “Billy Graham: the world is his pulpit”. Saturday Evening Post.

- ^ “Billy Graham, InterVarsity & New York City”. intervarsity.org. June 21, 2005. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ “William Borden: No Reserves. No Retreats. No Regrets”. Home.snu.edu. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ For Christ and the University: The Story of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship of the USA – 1940–1990 by Keith Hunt and Gladys Hunt, InterVarsity Press, 1991.[page needed]

- ^ “Oliver Barclay” (PDF). The Times. London. October 4, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 10, 2014. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ “Rev. Billy Graham: His Life By The Numbers, Years, and Millions”. WFMY. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ “My Answer from the writings of the Rev. Billy Graham | Tribune Content Agency”. Tribune Content Agency. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ “Formats and Editions of Decision magazine”. Worldcat. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ “New Billy Graham outreach: Hosting ‘Matthew parties’ to share the gospel”. al.com. April 16, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ Jenkins, Colleen (October 31, 2013). “Evangelist Billy Graham to mark 95th birthday with message to America”. Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- ^ Schier 2013, pp. 404–5.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Miller 2009, pp. 13–38.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h “Graham, William Franklin”. Martin Luther King Jr. And The Global Freedom Struggle. Stanford University. May 8, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Remembering Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: Gun Fire 45 Years Ago Kills Man that Billy Graham Considered a Friend Billy Graham.com, April 4, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2013

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Aikman 2010, pp. 195–203.

- ^ “To Billy Graham” (PDF). Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ “From Grady Wilson” (PDF). Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ Long 2008, pp. 150–151.

- ^ “The Archive – The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change”. thekingcenter.org. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ Blake, John (February 22, 2018). “Where Billy Graham ‘missed the mark’”. CNN. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Emerson, Michael O.; Smith, Christian (July 20, 2000). Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America. Oxford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0195147070. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ “Billy Graham passes away: Andrew Young remembers the reverend”. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ FOX (February 22, 2018). “Civil rights leader reflects on Billy Graham’s impact on Atlanta, movement”. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Billy Graham passes away: Congressman John Lewis remembers the reverend 11 Alive, February 21, 2018, Accessed October 6, 2020

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Billy Graham: an appreciation”. Baptist History and Heritage. June 22, 2006. Archived from the original on August 29, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ “Religion: A Challenge from Evangelicals”. Time. August 5, 1974. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ “Churchwoman to give talk”. The Oklahoman. October 26, 1996. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Graham, Billy (July 16, 1974). Why Lausanne? (Audio recording). Lausanne, Switzerland: Billy Graham Center Archives.

- ^ Stott, John (1997). “Foreword by Billy Graham”. Making Christ known: historic mission documents from the Lausanne Movement, 1974–1989. US: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8028-4315-8.

- ^ Kennedy, John W. (September 29, 2010). “The Most Diverse Gathering Ever”. Christianity Today. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Grant Wacker. America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation Look for the purposes 2014 p. 2.

- ^ “‘Man in the 5th Dimension’”. The 70 mm Newsletter. March 6, 2005. Archived from the original on May 25, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ Hirsch, Foster (2001). Love, Sex, Death & The Meaning of Life: The Films of Woody Allen. Da Capo Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-306-81017-4.

- ^ Gibbs, Nancy; Duffy, Michael (May 31, 2007). “Billy Graham: A Spiritual Gift to All”. Time. Archived from the original on June 3, 2007.

- ^ Aikman 2007, pp. 109–10.

- ^ [1] Archived December 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl (October 16, 1989). “Billy Graham Now a Hollywood Star”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ “My Hope With Billy Graham Mission Statement”. My Hope America Website. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Staff, JournalNow. “Billy Graham has brain shunt adjusted”. Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Tim Funk, “Lion in Winter: Billy Graham, Hearing and Sight Failing, Pays a Visit” Archived September 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Charlotte Observer, April 2010.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “A Family at Cross-Purposes”. The Washington Post. December 13, 2006. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Graham’s wife in coma, close to death; both will be buried at library”. The Herald. June 14, 2007. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ Bailey, Sarah Pulliam (January 12, 2017). “How Donald Trump is bringing Billy Graham’s complicated family back into White House circles”. The Washington Post.

- ^ “Rev. Billy Graham on his lasting legacy”. Today Show. June 23, 2005. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Study Guide: God in America, Episode 5, “The Soul of America” PBS Frontline, October 2010, program available online

- ^ “God in America: ‘The Soul of a Nation’”. PBS. October 11, 2010. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

Billy Graham convenes a meeting of American Protestant ministers in Montreux, Switzerland, for the purpose of discussing how they could ensure that John Kennedy would not be elected in November

- ^ Funk, Tim (February 21, 2018). “The Presidents’ preacher: From Truman to Trump”. The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Mize, Douglas W. (November 2, 2013). “John F. Kennedy, Billy Graham: irrecoverable moments in 1963”. Baptist Press. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Crosbie, Robert C. (November 18, 2013). “Billy Graham’s Warning to JFK”. HuffPost. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Steinfels, Peter (February 3, 1993). “America’s Pastor: At 74, Billy Graham Begins to Sum Up, Regrets and All”. The New York Times. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ Staff (January 27, 2017). “Why Is Abortion Such a Big Issue For Christians?”. Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h King, Randall E. (March 22, 1997). “When worlds collide: politics, religion, and media at the 1970 East Tennessee Billy Graham Crusade”. Journal of Church and State. 39 (2): 273–295. doi:10.1093/jcs/39.2.273. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ Merritt, Jonathan (February 21, 2018). “Billy Graham, the Last Nonpartisan Evangelical?”. The New York Times.

- ^ “Pilgrim’s Progress”. Newsweek. August 14, 2006. p. 4. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ O’Keefe, Ed (October 11, 2012). “Billy Graham to Mitt Romney: ‘I’ll do all I can to help you’”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ “Billy Graham site removes Mormon ‘cult’ reference after Romney meeting”. CNN. October 16, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ “Billy Graham Website Removes Mormon ‘Cult’ Reference After Romney Meeting”. HuffPost. October 16, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ Gordon, Michael (October 24, 2012). “Billy Graham speaks with his own voice, son Franklin says”. McClatchy News Service.

- ^ “My father voted for Trump: Franklin Graham responds to anti-Trump op-ed”. WVLT8. December 20, 2019.

- ^ Miller, Merle (1974). Plain Speaking: An Oral Biography of Harry S. Truman. New York: Putnam. p. 363.

- ^ Wacker, Grant (April 1, 1992). “Charles Atlas with a Halo”. The Christian Century. pp. 336–41.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “The President Preacher; In Crisis, White House Turns to Billy Graham”. The Washington Post. January 18, 1991. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Aikman 2010, pp. 204–205.

- ^ H. Larry Ingle, Nixon’s First Cover-up: The Religious Life of a Quaker President. pp. 101–04, University of Missouri Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0-8262-2042-4

- ^ Jump up to:a b Aikman 2010, pp. 203–210.

- ^ “The Essence of Billy Graham; A Warm but Honest Biography of the Evangelist”. The Washington Post. October 25, 1991. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ Elliston, Jon (August 23, 2013). “Billy Graham ‘absolutely crushed’ by Richard Nixon’s profanity in White House recordings”. carolinapublicpress.org. Carolina Public Press. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ “Remembering Billy Graham”. nixonfoundation.org. Richard Nixon Foundation. February 21, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ “Biography of Evangelist Billy Graham”. Christianity.about.com. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- ^ Baker, Peter (April 25, 2010). “Obama Visits the Rev. Billy Graham”. The New York Times. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ “Billy Graham Reflects on His Friendship with Queen Elizabeth II”. Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ “The Crown: The Truth Behind Queen Elizabeth’s Real-Life Friendship with Evangelist Billy Graham”. People. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ Loughrey, Clarisse (February 21, 2018). “Billy Graham dead: Truth behind Queen Elizabeth II’s friendship with the US evangelical preacher”. The Independent. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ Alexander Cockburn (September 2, 2005). “The plan to kill a million people”. Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ “Dr. Billy Graham trying to avoid offending Soviets”, United Press International story in Minden Press-Herald, May 10, 1982, p. 1

- ^ Preacher power: America’s God squad Archived August 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Independent Article, Preacher power: America’s God squad, July 25, 2007;

- ^ Jump up to:a b Billy Graham Responds to Lingering Anger Over 1972 Remarks on Jews, The New York Times, March 17, 2002

- ^ “Graham regrets Jewish slur”, BBC, March 2, 2002.

- ^ “Graham Apology Not Enough”, Eric J. Greenberg, United Jewish Communities.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Pilgrim’s Progress, p. 5”. Newsweek. August 14, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ Newton, Christopher (Associated Press Writer) (March 2, 2002). “Billy Graham apologizes for anti-Semitic comments in 1972 conversation with Nixon”. BeliefNet. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ “Revelation 3:9”. Bible Gateway.

- ^ Grossman, Cathy Lynn (June 24, 2009). “In Nixon tapes, Billy Graham refers to ‘synagogue of Satan’”. USA Today. Archived from the original on June 28, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- ^ Wirt, Sherwood Eliot (1997). Billy: A Personal Look at Billy Graham, the World’s Best-loved Evangelist. Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books. p. 97. ISBN 0-89107-934-3.

- ^ Cited in Iain Murray, Evangelicalism Divided (2000), pp. 73–74.

- ^ Iain Murray, Evangelicalism Divided (2000), p. 74.

- ^ Graham, Billy (December 1970). “Jesus and the Liberated Woman”. Ladies’ Home Journal. 87: 40–4.

- ^ “Billy Graham Enters Women’s Lib Controversy”. The Kokomo Tribune. November 28, 1970. p. 7.

- ^ “Feminist Chronicles – 1970”. Feminist Majority Foundation. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- ^ Dow, Bonnie J. (2014). Watching Women’s Liberation, 1970: Feminism’s Pivotal Year on the Network News. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-252-09648-8.

- ^ Alston, ShaKea (May 24, 2015). “1970: Feminist Sit in at Ladies Home Journal”.

- ^ Marshall, Ellen Ott (2008). “A Matter of Pride, A Feminist Response”. In Long, Michael G. (ed.). The Legacy of Billy Graham: Critical Reflections on America’s Greatest Evangelist. pp. 79–91. ISBN 978-0-664-23656-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Martin, William (February 21, 2018). “Divorce, drugs, drinking: Billy Graham’s children and their absent father”. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “About Anne Graham Lotz”. AnGel Ministries. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ AP via Washington Post “Billy Graham’s Wife Ruth Dies at 87” June 15, 2007[dead link]

- ^ Los Angeles “Ruth Graham, 87; had active role as wife of evangelist” June 15, 2007

- ^ Sanders, Linley (February 21, 2018). “Internet Reacts to Obama Tweet About Billy Graham”. Teen Vogue. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ Morris, Tim (February 25, 2018). “The complicated legacy of Billy Graham: Gospel or politics?”. The Times-Picayune. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gjelten, Tom (February 21, 2018). “‘America’s Pastor’ Billy Graham Dies at 99”. NPR. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ Billy Graham: Influential US evangelist dies at 99. BBC News, February 21, 2018.

- ^ Ed Kilgore, Billy Graham Lived at the Crossroads of Faith and Power, New York, February 21, 2018

- ^ Billy Graham urges anti-gay vote in N.C.. Wisconsin Gazette, May 12, 2012.

- ^ Siemaszko, Corky (February 21, 2018). “Franklin Graham followed in his father Billy’s footsteps, but took a right-leaning path”. NBC News. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ “Homosexuality And Religion:An Introduction”. Religious Tolerance.org. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ Robertson, Douglas (February 22, 2018). “The outpouring of grief for evangelist Billy Graham is disturbing given his homophobic views”. The Independent. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ^ “The Billy pulpit: Graham’s career in the mainline”. Christian Century. November 15, 2003. p. 2. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ Friedman, Corey (October 10, 2009). “Former Belmont Abbey College president dies at 85”. Gaston Gazette.

- ^ “Remarks at the Presentation Ceremony for the Presidential Medal of Freedom”. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ “Billy and Ruth Graham awarded Congressional Gold Medal for service”. Knight-Ridder News Service. May 2, 1996. Archived from the original on October 4, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ “Inductees Archive: Billy Graham”. Archived February 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine GMA Gospel Music Hall of Fame. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ^ CNN. “Remembering Billy Graham: A timeline of the evangelist’s life and ministry”. ABC Action News. February 21, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2018.