-

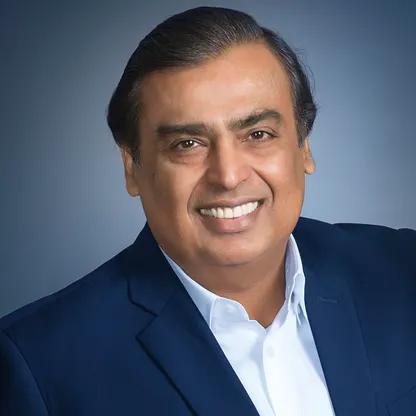

Mukesh Ambani

Mukesh Dhirubhai Ambani (born 19 April 1957) is an Indian billionaire businessman, and the chairman, managing director, and largest shareholder of Reliance Industries Ltd. (RIL), a Fortune Global 500 company and India’s most valuable company by market value.[4] According to Forbes, he is the richest person in Asia with a net worth of US$90.3 billion[5][6] and the 10th richest person in the world, as of 12 February 2022.

Contents

- 1Early life

- 2Education

- 3Career

- 4Timeline

- 5Board memberships

- 6Awards and honors

- 7Personal life

- 8See also

- 9References

- 10External links

Early life[edit source]

Mukesh Dhirubhai Ambani was born on 19 April 1957 in the British Crown colony of Aden (present-day Yemen) to Dhirubhai Ambani and Kokilaben Ambani. He has a younger brother Anil Ambani and two sisters, Nina Bhadrashyam Kothari and Dipti Dattaraj Salgaonkar.

Ambani lived only briefly in Yemen, because his father decided to move back to India in 1958[7] to start a trading business that focused on spices and textiles. The latter was originally named “Vimal” but later changed to “Only Vimal”.[8][9] His family lived in a modest two-bedroom apartment in Bhuleshwar, Mumbai until the 1970s.[10] The family’s financial status slightly improved when they moved to India but Ambani still lived in a communal society, used public transportation, and never received an allowance.[11] Dhirubhai later purchased a 14-floor apartment block called ‘Sea Wind’ in Colaba, where, until recently, Ambani and his brother lived with their families on different floors.[12]

Education[edit source]

Ambani attended the Hill Grange High School at Peddar Road, Mumbai, along with his brother and Anand Jain, who later became his close associate.[13] After his secondary schooling, he studied at the St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai.[14] He then received a BE degree in chemical engineering from the Institute of Chemical Technology.[15][16]

Ambani later enrolled for an MBA at Stanford University, but withdrew in 1980 to help his father build Reliance, which at the time was still a small but fast-growing enterprise.[15] His father felt that real-life skills were harnessed through experiences and not by sitting in a classroom, so he called his son back to India from Stanford to take command of a yarn manufacturing project in his company.[11]

Ambani has been quoted as saying that he was influenced by his teachers William F. Sharpe and Man Mohan Sharma because they are “the kind of professors who made you think out of the box.”[15]

Career[edit source]

In 1981 he started to help his father Dhirubhai Ambani run their family business, Reliance Industries Limited. By this time, it had already expanded so that it also dealt in refining and petrochemicals. The business also included products and services in retail and telecommunications industries. Reliance Retail Ltd., another subsidiary, is also the largest retailer in India.[17] Reliance’s Jio has earned a top-five spot in the country’s telecommunication services since its public launch on 5 September 2016.

As of 2016, Ambani was ranked 36 and has consistently held the title of India’s richest person on Forbes magazine’s list for the past ten years.[18] He is the only Indian businessman on Forbes‘ list of the world’s most powerful people.[19] As of October 2020, Mukesh Ambani was ranked by Forbes as the 6th-wealthiest person in the world.[6] He surpassed Jack Ma, executive chairman of Alibaba Group, to become Asia’s richest person with a net worth of $44.3 billion in July 2018. He is also the wealthiest person in the world outside North America and Europe.[20] As of 2015, Ambani ranked fifth among India’s philanthropists, according to China’s Hurun Research Institute.[21] He was appointed as a Director of Bank of America and became the first non-American to be on its board.[22]

Through Reliance, he also owns the Indian Premier League franchise Mumbai Indians and is the founder of Indian Super League, a football league in India.[23] In 2012, Forbes named him one of the richest sports owners in the world.[24] He resides at the Antilia Building, one of the world’s most expensive private residences with its value reaching $1 billion.[25]

Timeline[edit source]

1980s–1990s[edit source]

In 1980, the Indian government under Indira Gandhi opened PFY (polyester filament yarn) manufacturing to the private sector. Dhirubhai Ambani applied for a license to set up a PFY manufacturing plant. Obtaining the license was a long-drawn-out process requiring a strong connection within the bureaucracy system because the government, at the time, was restricting large-scale manufacturing, making the importation of yarn for the textiles impossible.[26] In spite of stiff competition from Tatas, Birlas and 43 others, Dhirubhai was awarded the license, more commonly addressed as License Raj.[27] To help him build the PFY plant, Dhirubhai pulled his eldest son out of Stanford, where he was studying for his MBA, to work with him in the company. Ambani did not return to his university program, leading Reliance’s backward integration, where companies own their suppliers to generate more revenue and improve efficiency, in 1981 from textiles into polyester fibers and further into petrochemicals, which the yarns were made from.[4] After joining the company, he reported daily to Rasikbhai Meswani, then executive director. The company was being built from scratch with the principle of everybody contributing to the business and not heavily depend on selected individuals. Dhirubhai treated him as a business partner allowing him the freedom to contribute even with little experience.[11] This principle came into play after Rasikbhai’s death in 1985 along with Dhirubhai suffering a stroke in 1986 when all the responsibility shifted to Ambani and his brother.[28] Mukesh Ambani set up Reliance Infocomm Limited (now Reliance Communications Limited), which was focused on information and communications technology initiatives.[29] At the age of 24, Ambani was given charge of the construction of Patalganga petrochemical plant when the company was heavily investing in oil refinery and petrochemicals.[30]

2000s–present[edit source]

On 6 July 2002, Mukesh’s father died after suffering a second stroke,[31] which elevated tensions between the brothers as Dhirubhai had not left a will for the distribution of the empire in 2004.[32] Their mother intervened to stop the feud, splitting the company into two, Ambani receiving control of Reliance Industries Limited and Indian Petrochemicals Corporation Limited, which was later approved by the Bombay High Court in December 2005.[33][34]

Ambani directed and led the creation of the world’s largest grassroots petroleum refinery at Jamnagar, India, which had the capacity to produce 660,000 barrels per day (33 million tonnes per year) in 2010, integrated with petrochemicals, power generation, port, and related infrastructure.[35] In December 2013 Ambani announced, at the Progressive Punjab Summit in Mohali, the possibility of a “collaborative venture” with Bharti Airtel in setting up digital infrastructure for the 4G network in India.[36] On 18 June 2014, Mukesh Ambani, while addressing the 40th AGM of Reliance Industries, said he will invest Rs 1.8 trillion (short scale) across businesses in the next three years and launch 4G broadband services in 2015.[37]

Ambani was elected as a member into the National Academy of Engineering in 2016 for engineering and business leadership in oil refineries, petrochemical products, and related industries.[38] In February 2016, Ambani-led Jio launched its own 4G smartphone brand named LYF.[39] In June 2016, it was India’s third-largest-selling mobile phone brand.[40] The release of the service Reliance Jio Infocomm Limited, commonly known as Jio, in September 2016 was a success, and Reliance’s shares increased.[41] During the 40th annual general meeting of RIL, he announced bonus shares in the ratio of 1:1 which is the country’s largest bonus issue in India, and announced the Jio Phone at an effective price of ₹0.[42] As of February 2018, Bloomberg’s “Robin Hood Index” estimated that Ambani’s personal wealth was enough to fund the operations of the Indian federal government for 20 days.[43]

In February 2014, a First Information Report (FIR) alleging criminal offenses was filed against Mukesh Ambani for alleged irregularities in the pricing of natural gas from the KG basin.[44] Arvind Kejriwal, who had a short stint as Delhi‘s chief minister and had ordered the FIR, has accused various political parties of being silent on the gas price issue.[45] Kejriwal has asked both Rahul Gandhi and Narendra Modi to clear their stand on the gas pricing issue.[46][47] Kejriwal has alleged that the Centre allowed the price of gas to be inflated to eight dollars a unit though Mukesh Ambani’s company spends only one dollar to produce a unit, which meant a loss of Rs. 540 billion to the country annually.[48][49]

Board memberships[edit source]

- Member of Board of Governors Institute of Chemical Technology, Mumbai

- Chairman, managing director, Chairman of Finance Committee and Member of Employees Stock Compensation Committee, Reliance Industries Limited

- Former chairman, Indian Petrochemicals Corporation Limited

- Former vice-chairman, Reliance Petroleum

- Chairman of the board, Reliance Petroleum

- Chairman and Chairman of Audit Committee, Reliance Retail Limited

- Chairman, Reliance Exploration and Production DMCC

- Former Director, Member of Credit Committee and Member of Compensation & Benefits Committee, Bank of America Corporation[50]

- President, Pandit Deendayal Petroleum University, Gandhinagar, Gujarat

Awards and honors[edit source]

Year of Award or Honor Name of Award or Honor Awarding Organization 2000 Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year[51] Ernst & Young India 2010 Global Vision Award at The Awards Dinner[52] Asia Society 2010 Business Leader of the Year[53] NDTV India 2010 Businessman of the Year[54] Financial Chronicle 2010 School of Engineering and Applied Science Dean’s Medal[55] University of Pennsylvania 2010 ranked 5th-best performing global CEO[56] Harvard Business Review 2010 Global Leadership Award[57] Business Council for International Understanding 2010 Honorary Doctorate (Doctor of Science)[58] M. S. University of Baroda 2013 Millennium Business Leader of the Decade at Indian Affairs India Leadership Conclave Awards 2013)[59] India Leadership Conclave & Indian Affairs Business Leadership Awards 2016 Foreign associate, U.S. National Academy of Engineering[60][61] National Academy of Engineering 2016 Othmer Gold Medal[62][63] Chemical Heritage Foundation Personal life[edit source]

He married Nita Ambani in 1985 and they have two sons, Akash and Anant, and a daughter, Isha, who is Akash’s twin.[3][64] They met after his father attended a dance performance which Nita took part in and thought of the idea of arranging a marriage between the two.[65]

They live in Antilia, a private 27-storey building in Mumbai, which was valued at US$1 billion and was the most expensive private residence in the world at the time it was built.[25][66] The building requires a staff of 600 for maintenance, and it includes three helipads, a 160-car garage, private movie theater, swimming pool, and fitness center.[67]

In 2007, Ambani gifted his wife a $60 million Airbus A319 for her 44th birthday.[68] The Airbus, which has a capacity of 180 passengers, has been custom-fitted to include a living room, bedroom, satellite television, WiFi, sky bar, Jacuzzi, and an office.[69]

Ambani was titled “The World’s Richest Sports Team Owner” after his purchase of the IPL cricket team Mumbai Indians for $111.9 million in 2008.[70][71]

In an interview with Rajdeep Sardesai in March 2017, he said that his favourite food continued to be idli sambar and his favourite restaurant remains Mysore Café, a restaurant in King’s Circle (Mumbai) where he used to eat as a student at UDCT.[72] Mukesh Ambani is a strict vegetarian and teetotaler.[73] He is a very big fan of Bollywood movies, watching three a week because he says “you need some amount of escapism in life.”[11][32]

During the fiscal year ending 31 March 2012, he reportedly decided to forgo nearly ₹240 million from his annual pay as chief of Reliance Industries Ltd (RIL). He elected to do this even as RIL’s total remuneration packages to its top management personnel increased during that fiscal year. Mukesh Ambani holds a 50.4% stake in the company.[74] This move kept his salary capped at ₹150 million for the fourth year in a row.[75]

In early 2019, a court in Mumbai held his younger brother, Anil Ambani, in criminal contempt for non-payment of personally guaranteed debt Reliance Communications owed to Swedish gearmaker Ericsson. Instead of jail time, the court gave Anil a month to come up with the funds. At the end of the month, Mukesh bailed out his younger brother, paying the debt.[33]

See also[edit source]

References[edit source]

- ^ L. Nolen, Jeannette. “Mukesh Ambani”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ “The Rediff Business Interview/ Mukesh Ambani”. Rediff.com. 17 June 1998. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Karmali, Naazneen (6 April 2016). “Meet Nita Ambani, The First Lady of Indian Business”. Forbes. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Mukesh Ambani :: RIL :: Reliance Group of Industries”. Reliance Industries Limited. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani”. Forbes. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Real Time Billionaires”. Forbes. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Majumdar, Shyamal (14 January 2015). “How Dhirubhai Ambani changed the style of doing business in India”. Rediff.com. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Pandey, Piyush (22 June 2012). “RIL set to part with ‘Only Vimal’ brand”. The Times of India. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Life story of Mukesh Ambani”. truthofthoughts.com. 23 February 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ “Reliance didn’t grow on permit raj: Anil Ambani”. Rediff.com. 11 May 2002. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Giridharadas, Anand (15 June 2008). “Meet Mukesh Ambani: India’s Richest Man”. The New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Yardley, Jim (28 October 2010). “Soaring Above India’s Poverty, a 27-Story Home”. The New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Bhupta, Malini (17 January 2005). “Anand Jain: A bone of contention between the Ambani brothers”. India Today. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Fernandes, Kasmin (2 January 2010). “St. Xavier’s is the Indian Hogwarts”. Mid-Day. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Mukesh Ambani on his childhood, youth”. Rediff.com. 19 January 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Ambani, Mukesh (2001). “Re-Orienting Education at UDCT”. The Bombay Technologist. 50 (1): 33–35. ISSN 0067-9925. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Kumar, Abhineet (17 August 2013). “Ambani tops retailer list, too”. Business Standard. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Bill Gates richest man in world, Mukesh Ambani at 36th: Forbes”. The Economic Times. 2 March 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “The World’s Most Powerful People”. Forbes. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Billionaire Mukesh Ambani topples Jack Ma as Asia’s richest person”. The Times of India. 13 July 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Balachandran, Manu (5 January 2015). “India’s biggest philanthropist is seven times more generous than the next”. Quartz India. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani appointed Bank of America as director”. The Economic Times. 16 March 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ Hiscock, Geoff (14 December 2010). “Indian tycoon Mukesh Ambani backs new soccer league”. Herald Sun. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Richest Owners in Sports: Mukesh Ambani”. Forbes. 12 March 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Magnier, Mark (24 October 2010). “Mumbai billionaire’s home boasts 27 floors, ocean and slum views”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Agarwal, Neeraj (30 March 2016). “India Before 1991: Stories of Life Under the License Raj”. Spontaneous Order. Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ “Reliance Industries Ltd. – Company Profile, Information, Business Description, History, Background Information on Reliance Industries Ltd”. referenceforbusiness.com. Advameg Inc. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani – In His Own Words”. wealthymatters. 4 February 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ “Reliance Infocomm Ushers a Digital Revolution in India”. Press Release by Reliance Infocomm. Reliance Communications. 27 December 2002. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ Poza, Ernesto J. (29 January 2009). Family Business. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0324597691.

- ^ Bagchi, Pradipta (7 July 2002). “Dhirubhai Ambani passes away”. The Times of India. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “An insight into Mukesh Ambani’s empire and how he became Asia’s richest man”. The National. 15 July 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Altstedter, Ari; Sanjai, P. R. (3 June 2020). “Mukesh Ambani Won the World’s Most Expensive Sibling Rivalry”. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Badkar, Mamta (26 May 2011). “The Full Story of the Massive Feud Between The Billionaire Ambani Brothers”. Business Insider. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani :: Reliance Group :: Reliance Petroleum Limited :: Reliance Industries”. Reliance Industries Limited. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani hints at venture between Reliance Industries and Bharti Airtel”. The Indian Express. 9 December 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Reliance 4G services to be launched in 2015: Mukesh Ambani”. ABP News. 18 June 2014. Archived from the original on 19 June 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani elected to National Academy of Engineering, one of only 10 Indians”. Firstpost. 8 February 2016. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Gloria Singh, Surbhi (15 May 2016). “Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Jio Infocomm’s LYF mobile: A whopping $1 billion brand?”. Financial Express. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Agarwal, Sapna; Pathak, Kalpana (29 June 2016). “How Reliance Jio’s LYF became India’s third-largest selling phone brand”. Mint. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Sundria, Saket (13 July 2018). “Analysis | Who Is Mukesh Ambani, Asia’s Newest Richest Man?: QuickTake”. Bloomberg. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ Verma, Swati (7 January 2018). “Macro cues, Q3 earnings, and oil prices to sway market this week”. The Economic Times. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ Strauss, Marine; Lu, Wei (11 February 2018). “What If the World’s Richest Paid for Government Spending?”. Bloomberg. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ “Arvind Kejriwal rakes up K G Basin gas pricing, orders FIRs against Moily, Deora, Mukesh Ambani”. The Indian Express. 11 February 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Nair, Anisha (23 February 2014). “Arvind Kejriwal calls BJP, Congress puppets of Mukesh Ambani”. Oneindia. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Arvind Kejriwal’s letter to Mukesh Ambani on gas pricing”. NDTV. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Ghosh, Deepshikha (21 February 2014). “Clear your stand on Mukesh Ambani: Arvind Kejriwal tells Narendra Modi, Rahul Gandhi”. NDTV. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Arvind Kejriwal fires on all cylinders, now writes to Rahul Gandhi over gas prices involving Mukesh Ambani”. India Today. 24 February 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Arvind Kejriwal asks Narendra Modi to come clean on gas pricing”. DNA. 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Mukesh Dhirubhai Ambani, Reliance Industries: Profile and Biography”. Bloomberg. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Entrepreneur of the Year – 2000 Winners”. Ernst & Young. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ “Asia Society Awards Dinner Honors Mukesh Ambani, Jeffrey Immelt, and NY Philharmonic”. Press Release on Asia Society. Asia Society. 4 November 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ “Winners of the NDTV Profit Business Leadership Awards”. NDTV Convergence Limited. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ T. Joseph, Anto (30 December 2010). “FC Businessman of the Year: Mukesh Ambani”. Financial Chronicle. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani awarded the Dean’s Medal by University of Pennsylvania”. Forbes India. 9 January 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ T. Hansen, Morten; Ibarra, Herminia; Peyer, Urs (January 2010). “Mukesh D. Ambani – 100 Best-Performing CEOs in the World”. Harvard Business Review. Harvard Business Publishing. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “BCIU Presents Dwight D. Eisenhower Global Awards to Mukesh D.” Bloomberg. 11 November 2010. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ “MSU doctorate for Mukesh Ambani”. The Economic Times. 30 September 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Priyanka Chopra, Manish Malhotra, Dr. Mukesh Batra, Ratan Tata, Mukesh Ambani, Dr. Laud, Dr. Mukesh Hariawala, Dilip Surana Among Others to Receive Prestigious India Leadership Conclave Awards 2013”. indiainfoline.com. India Infoline. 20 June 2013. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Four Indian American Engineers Among Newly Elected NAE Members”. India West. 9 February 2016. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ “Mr. Mukesh Dhirubhai Ambani”. National Academy of Engineering. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani awarded Othmer Gold Medal for Entrepreneurial Leadership”. NetIndian News Network. 17 May 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ “Othmer Gold Medal”. Science History Institute. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “India’s young billionaire heirs and heiresses”. India TV. 28 November 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Vartak, Priyanka (24 November 2017). “Nita Ambani’s story, from school teacher to India’s wealthiest woman, is worth a read!”. The Free Press Journal. Archived from the original on 24 November 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Kwek, Glenda (15 October 2010). “India’s richest man builds world’s first billion-dollar home”. The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Hanrahan, Mark (18 May 2012). “Antilia: Inside Mukesh Ambani’s 27-Story Mumbai Residence, The World’s First $1 Billion Home (PHOTOS)”. HuffPost. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani gifts wife jet on birthday”. Reuters. 2 November 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani gifts Rs 240 cr jet to wife”. Rediff.com. 3 November 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Big business and Bollywood grab stakes in IPL”. ESPNcricinfo. 24 January 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Badenhausen, Kurt (7 March 2018). “The World’s Richest Sports Team Owners 2018”. Forbes. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ D’Mello, Yolande (16 October 2011). “Number munching at Cafe Mysore”. Mid-Day. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani is India’s richest man for the second year in a row”. thomaswhite.com. 1 June 2010. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ Chu, Patrick; Idayu Ismail, Netty (5 March 2012). “Mukesh Ambani Backed by India Power Holdings Proves Asia’s Top Billionaire”. Bloomberg. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ “Mukesh Ambani forgoes Rs 23.82 crore from his pay package”. The Times of India. 9 May 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

-

Gina Rinehart

Minister for Trade and Investment Andrew Robb joins Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Australia’s high commissioner in India Patrick Suckling at Gina Rinehart’s book launch. Georgina Hope “Gina” Rinehart AO (née Hancock, born 9 February 1954) is an Australian mining magnate and heiress.[8] Rinehart is the Executive Chairman of Hancock Prospecting, a privately-owned mineral exploration and extraction company founded by her father, Lang Hancock.

Rinehart was born in Perth, Western Australia, and spent her early years in the Pilbara region. She boarded at St Hilda’s Anglican School for Girls and then briefly studied at the University of Sydney, dropping out to work with her father at Hancock Prospecting. She was Lang Hancock’s only child, and when he died in 1992 – leaving a bankrupt estate – she succeeded him as executive chairman.[9] She turned a company with severe financial difficulties into the largest private company in Australia and one of the largest mining houses in the world.[9][10]

When Rinehart took over Hancock Prospecting, its total wealth was estimated at A$75 million, which did not account for group liabilities and contingent liabilities. She oversaw an expansion of the company over the following decade, and due to the iron ore boom of the early 2000s became a nominal billionaire in 2006. In the 2010s, Rinehart began to expand her holdings into areas outside the mining industry. She made sizeable investments in Ten Network Holdings and Fairfax Media (although she sold her interest in the latter in 2015), and also expanded into agriculture, buying several cattle stations.[citation needed]

Rinehart is Australia’s richest person. Her wealth reached around A$29 billion in 2012, at which point she overtook Christy Walton as the world’s richest woman and was included on the Forbes list of The World’s 100 Most Powerful Women. Rinehart’s net worth dropped significantly over the following few years due to a slowdown in the Australian mining sector. Forbes estimated her net worth in 2019 at US$14.8 billion as published in the list of Australia’s 50 richest people.[11] However, her wealth was rebuilt again during 2020 due to increased demand for Australian iron ore,[12] so that by May 2021, her net worth as published in the 2021 Financial Review Rich List was estimated in excess of A$30 billion;[7] while in March 2021, The Australian Business Review stated her wealth equalled A$36.28 billion.[13][14] As of September 2020 Forbes considered Rinehart one of the world’s ten richest women.[15] Rinehart was Australia’s wealthiest person from 2011 to 2015, according to both Forbes and The Australian Financial Review; and again in 2020 and 2021, according to The Australian Business Review and The Australian Financial Review.[7][16][14] In a May 2021 Guardian Australia investigation, it was reported that Rinehart was the single largest landholder in Australia, at over 9.2 million hectares (23 million acres), just over 1% of Australia’s total landmass.[17] In October 2021, she garnered controversy after expressing climate change denialist views during a speech at her childhood primary school.[18]

Contents

- 1Early life and family

- 2Business career

- 3Political activities

- 4Hope Margaret Hancock Trust

- 5Net worth

- 6Awards

- 7References

- 8Further reading

- 9External links

Early life and family[edit source]

Rinehart was born on 9 February 1954 at St John of God Subiaco Hospital in Perth, Western Australia.[19] She is the only child of Hope Margaret Nicholas and Lang Hancock. Until age four, Rinehart lived with her parents at Nunyerry, 60 kilometres (37 mi) north of Wittenoom. Her family then moved to Mulga Downs station in the Pilbara.[20] Later Rinehart boarded at St Hilda’s Anglican School for Girls in Perth. She briefly studied economics at the University of Sydney, before dropping out and working for her father, gaining an extensive knowledge of the Pilbara iron-ore industry. Rinehart rebuilt the HPPL company to become one of the most successful private companies in Australia’s history.[21][22]

In 1973, at age 19, Rinehart met Englishman Greg Milton while both were working in Wittenoom. At this time Milton changed his surname to an earlier family name Hayward. Their children John Langley[3] and Bianca Hope were born in 1976 and 1977 respectively. The couple separated in 1979 and divorced in 1981.[23]: 6 [23]: 7 [22] In 1983, she married corporate lawyer and Arco executive, Frank Rinehart,[23]: 4 in Las Vegas. They had two children, Hope and Ginia, born in 1986 and 1987 respectively. Frank Rinehart received a scholarship to Harvard for his services in the then US Army air Corp. He was top of Harvard College, and then top of Harvard Law School, while also studying engineering, and holding a full-time and two part time jobs.[24][25] Frank Rinehart died in 1990.[23]: 10

Rinehart and, Rose Porteous, Lang Hancock’s estranged wife then widow, who married Willie Porteous soon after his passing, were involved in an acrimonious legal fight from 1992 over Hancock’s death and bankrupt estate. The ordeal ultimately took 14 years to settle. With HPPL retaining the mining tenements, Mrs Porteous had endeavored to allege did not belong to the company.[26]

In 1999, the Western Australian state government approved a proposal to name a mountain range in honour of her family. Hancock Range is situated about 65 kilometres (40 mi) north-west of the town of Newman at 23°00′23″S 119°12′31″E and commemorates the family’s contribution to the establishment of the pastoral and mining industry in the Pilbara region.[27][28]

In 2003, at age 27, Rinehart’s son John changed his surname by deed poll from his birth name Hayward to Hancock, his maternal grandfather’s name.[29] Since 2014, Rinehart has had a difficult relationship with her son, John; and was not present at his wedding to Gemma Ludgate.[21][30] John’s sister, Bianca Hope Rinehart, who was once positioned to take over the family business, served as a director of Hancock Prospecting and HMHT Investments until 31 October 2011, when she was replaced by her half-sister, Ginia Rinehart.[5][31][32] In 2013, Bianca married her partner Sasha Serebryakov, she married in Hawaii; and Rinehart did not attend the wedding.[30] Rinehart’s other daughter, Hope, married Ryan Welker, and they divorced while living in New York. Rinehart attended both her younger daughters’ weddings.[5]

Business career[edit source]

Main article: Hancock ProspectingA 20 class locomotive at 7 Mile Yard near Karratha, Western Australia which serves Hope Downs mine, co-owned by Hancock Group and Rio Tinto.

After the death of her father in March 1992, Rinehart became Executive Chairman of Hancock Prospecting Pty Limited (HPPL) and the HPPL Group of companies.[33][34] All companies within the group are privately-owned. With the notable exception of receiving a royalty stream from Hamersley Iron since the late 1960s, Lang Hancock’s mining activities were mainly related to exploration and the accumulation of vast mining leases. The BBC journalist, Nick Bryant, argues that while Rinehart was a beneficiary of her father’s royalty deals, she “transformed the family business by spotting, early than most, the vast potential of the China market.”[35]

Rinehart achieved the Roy Hill tenements in 1993, The year after her father’s death, having applied for them five months after her father’s passing, and focused on developing Roy Hill And Hancock Prospective undeveloped deposits, raising capital through joint venture partnerships and turning the leases into revenue producing mines.[36]

Hancock Prospecting, now owns 50 per cent of Hope Downs and shares of 50 per cent of the profits generated by the 4 Hope Downs mine, which is operated by Rio Tinto under a joint management committee and produces 47 million tonnes of iron ore annually. Another joint venture with Mineral Resources at Nicholas Downs, northwest of Newman, is producing 500 million tonnes of ferruginous manganese.[citation needed] The Alpha Coal, Tads Corner and Kevin’s Corner projects in Central Queensland,are expected to produce 30 million tonnes of coal each. The Roy Hill Iron ore project, south of Port headline, in the Pilbara produces 60 million tonnes a year, with approvals pending to reach 70 million tonnes per annum.

In 2010 Rinehart took a 10 per cent stake in Ten Network Holdings; James Packer had acquired an 18 per cent stake in the same company shortly before. Since then she also acquired a substantial stake in Fairfax Media. Rinehart was a major player in the media and no longer limits her interests to the mining business.[40] In February 2012 she increased her stake in Fairfax to over 12 per cent, and became the largest shareholder of the company.[41][42] Fairfax journalists were reportedly fearful that she wanted to turn them into a “mouthpiece for the mining industry”.[43] In June 2012, she increased her stake further to 18.67 per cent, and was believed to be seeking three board seats and involvement in editorial decisions in Fairfax’s newspaper division.[44] Negotiations between Fairfax and Hancock Prospecting broke down in late June because of disagreements over Fairfax’s editorial independence policy and other issues relating to board governance; chair Roger Corbett subsequently announced that Rinehart would not be offered any seats on the board.[45] After failing to get board representation she sold her shareholding in 2015.[46][47]

In 2015, Rinehart was listed as the 37th most powerful woman in the world by Forbes; a decline from her 2014 and 2013 rankings as the 27th and the 16th most powerful woman, respectively.[48][49]

Later the same year Rinehart acquired Fossil Downs Station after it was placed on the market for the first time in 133 years. The 4,000-square-kilometre (1,544 sq mi) property was stocked with 15,000 head of cattle and the sale price was not disclosed,[50] but estimated to be between A$25 to 30 million.[51] Rinehart had acquired a 50% stake in Liveringa and Nerrima Stations in 2014 for A$40 million in 2014.[50]

In October 2015, Rinehart planned to open the huge Roy Hill mine just eight months after she secured A$7.9 billion in funding. Initial shipments of iron ore were sent to China. In October 2016 it was announced that Hancock Prospecting had struck a deal to invest in AIM listed UK-based mining company Sirius Minerals to help bring to fruition their North Yorkshire Polyhalite Project.[52]

Political activities[edit source]

In the 1970s, Rinehart was an active supporter of the Westralian Secession Movement, which her father had founded to work for the secession of Western Australia from the rest of the country.[53] She also had some involvement with the Workers Party (later renamed the Progress Party), a libertarian organisation founded by businessman John Singleton.[54][55]

Rinehart opposed the Rudd government’s Mineral Resource Rent Tax and Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme as part of a group of mining magnates that included Andrew Forrest.[56] She founded the lobby group ANDEV, (“Australians for Northern Development and Economic Vision”)[57] and has sponsored the trips of prominent climate change denier Christopher Monckton to Australia.[58][59]

Since 2010 Rinehart has been actively promoting the cause of development of Australia’s north and has spoken, written articles and published a book on this topic.[60] Rinehart stresses that Australia must do more to welcome investment and improve its cost competitiveness, particularly when Australia faces record debt. She advocates a special economic zone in the North with reduced taxation and less regulations and has enlisted the support of many prominent Australians, plus the Institute of Public Affairs.[61] In a 2012 article in the Australian Resources and Investment Magazine, Rinehart said that if people wanted to have more money they should “stop whingeing” and “Do something to make more money yourself − spend less time drinking or smoking and socialising, and more time working”. She criticised what she saw as the “socialist” policies of the Australian Government of “high taxes” and “excessive regulation”.[62]

External video  Gina Rinehart YouTube Monologue, Sydney Mining Club

Gina Rinehart YouTube Monologue, Sydney Mining Club Gina Rinehart calls for Australian wage cut, BBC

Gina Rinehart calls for Australian wage cut, BBCIn a video posted to the Sydney Mining Club‘s YouTube channel on 23 August 2012, Rinehart expressed concern for Australia’s economic competitiveness noting how “Indeed if we competed in the Olympic Games as sluggishly as we compete economically, there would be an outcry.”[63] She said “Furthermore, Africans want to work and its workers are willing to work for less than two dollars a day. Such statistics make me worry for this country’s future.”[63] Rinehart’s views were dismissed by the Australian Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, who said that “It’s not the Australian way to toss people $2, to toss them a gold coin, and then ask them to work for a day” and that “we support proper Australian wages and decent working conditions.”[64] The Australian Deputy Prime Minister and Treasurer, Wayne Swan, described Rinehart’s statement as an “insult to the millions of Australian workers who go to work and slog it out to feed the kids and pay the bills.”[65]

Hope Margaret Hancock Trust[edit source]

In 1988, Lang Hancock established the Hope Margaret Hancock Trust, nominating Rinehart as trustee, with his four grandchildren named as beneficiaries.[66] Gina Rinehart was appointed to run the trust until the youngest of her four children, Ginia Rinehart, turned 25 in 2011.[67] The Trust owns 23.6% of the shares in Hancock Prospecting,[68] and as of June 2015 was believed to be valued at about A$5 billion.[67]

In 2011, Rinehart’s daughter, Hope Rinehart Welker, commenced a commercial action in the New South Wales Supreme Court for reasons understood to be related to the conduct of the trustee.[69] The action sought to remove Rinehart as sole trustee. Her brother, John, and sister, Bianca, were later revealed as parties to the dispute.[24][70][71]

In an agreement reached between the parties, the Court granted an interim non-publication order in September 2011. In making the interim order, Justice Paul Brereton stated: “This is not the first occasion of discord in the family, which has immense wealth, no small part of which resides in the trust. In the past, the affairs of the family, including such discord, has attracted considerable publicity in the media.”[72] Then, in a judgement handed down on 7 October 2011, Justice Brereton stated that he intended to dismiss an application by Rinehart, that there be a stay on court action, and that the family be directed into mediation.[66][73] In December 2011, three justices of the NSW Court of Appeal lifted the suppression orders on the case. However, a stay was granted until 3 February 2012[74] and extended by the High Court of Australia until 9 March 2012. Rinehart’s application for suppression was supported by Ginia Rinehart, but was opposed by Hope, John and Bianca.[75] A subsequent application by Rinehart for a non-publication order on the grounds of fear of personal and family safety was dismissed by the NSW Supreme Court on 2 February 2012.[76] In March 2012, when the suppression order was lifted, it was revealed that Rinehart had delayed the vesting date of the trust, which had prompted the court action by her three older children.[77]

Rinehart stood down as trustee during the hearing in October 2013.[78] While Rinehart’s lawyers subsequently declared any legal matters closed, John and Bianca’s legal representatives proceeded with a trial in the NSW Supreme Court to deal with allegations of misconduct.[79] The Court handed down its decision on 28 May 2015 in which Bianca was appointed as the new trustee.[67][80]

Net worth[edit source]

Rinehart is one of Australia’s richest people, with Forbes estimating her net worth in 2019 at US$14.8 billion as published in the list of Australia’s 50 richest people,[11] and The Australian Financial Review estimating her net worth in 2021 at A$31.06 billion—the wealthiest Australian as published in the 2021 Financial Review Rich List.[7] Forbes considers Rinehart one of the world’s richest women.

Rinehart first appeared on the 1992 Financial Review Rich List (at the time called the BRW Rich 200, published annually in the BRW magazine, following the death of her father earlier that year. She has appeared every year since, and became a billionaire in 2006. Due to Australia’s mining boom in the early 21st century, Rinehart’s wealth increased significantly since 2010, and she diversified investments into media, taking holdings in Ten Network Holdings and Fairfax Media. According to BRW, she became Australia’s richest woman in 2010, and Australia’s richest person in 2011, and the first woman to lead the list. During 2012, BRW claimed Rinehart was the world’s richest woman, surpassing Wal-Mart owner Christy Walton.[81]

In 2007, she first appeared on Forbes Asia Australia’s 40 Richest, with an estimated wealth of US$1 billion;[26] more than doubling that the next year to US$2.4 billion; and then, in spite of the global financial crisis, by 2011 had more than trebled to US$9 billion;[21] doubled again in 2012 to US$18 billion;[82] a slight reduction in 2013 to US$17 billion;[83] and a slight increase in 2014 to US$17.6 billion.[84] While still Australia’s richest person, her wealth had reduced to US$12.3 billion by 2015 according to Forbes,[85] and in 2016 Forbes assessed her net worth at US$8.5 billion, placing her second on the list.[86] Releasing the results in February 2011, Forbes was the first to name her as Australia’s richest person; with BRW conferring the same title in May that year.

In June 2011, Citigroup estimated that she was on course to overtake Carlos Slim, the Mexican magnate worth US$74 billion and Bill Gates, who is worth US$56 billion, mainly because she owns her companies outright. Using a price-to-earnings ratio of 11:1 that applied at that time to her business partner, Rio Tinto, the Australian internet business news service, SmartCompany, stated: “It is possible to see Rinehart’s portfolio of coal and iron ore production spinning off annual profits approaching US$10 billion”, giving her a “personal net worth valuation of more than US$100 billion”.[87][88]

In January 2012, there were further media reports that Rinehart’s estimated wealth has increased to A$20 billion following estimates that the Roy Hill project was notionally valued at A$10 billion.[89][90] Forbes magazine ranked her as the fourth-richest woman in 2012 with US$18 billion; the fifth-richest woman in 2013 with US$17 billion;[91] and the sixth-richest woman in 2014 with US$17.6 billion.[84] In 2012, BRW estimated her wealth at A$29.17 billion, with Ivan Glasenberg being her closest rival, with net wealth estimated at A$7.4 billion.[92] At the time, BRW stated that it was possible Rinehart would become the first person with a net wealth of US$100 billion.[93] As of December 2012, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, Rinehart was the 37th-richest person in the world, with an estimated net worth of US$18.6 billion.[94]

Rinehart’s wealth rankings between 2013 and 2019 were adversely impacted by the fall in the wholesale iron ore price and the fall in the AUD/USD exchange rate.[80][85] In May 2016, she had fallen from wealthiest Australian in 2011 to fourth, with A$6.06 billion, surpassed by property developer Harry Triguboff, with A$10.62 billion.[95] By 2020, according to The Australian Financial Review, Rinehart had an estimated net worth of A$28.89 billion and was restored to the mantle of the wealthiest Australian;[16] it was a title that she maintained in 2021, with an estimated net worth of A$31.06 billion.[7]

Wealth rankings[edit source]

Year Financial Review

Rich ListForbes

Australia’s 50 richestRank Net worth A$ Rank Net worth US$ 2006 8

$1.80 billion

2007[26][96] 4

$4.00 billion

14

$1.00 billion

2008[97][98] 5

$4.39 billion

6

$2.40 billion

2009[99][100] 4

$3.47 billion

7

$1.50 billion

2010[22][101] 5

$4.75 billion

9

$2.00 billion

2011[21][36] 1

$10.31 billion

1

$9.00 billion

2012[82][102] 1

$29.17 billion

1

$18.00 billion

2013[83][103] 1

$22.02 billion

1

$17.00 billion

2014[2][84] 1

$20.01 billion

1

$17.60 billion

2015[85][104][105] 1

$14.02 billion

1

$12.30 billion

2016[95] 4

$6.06 billion

2

$8.50 billion

2017[106] 3

$10.40 billion

1

$14.8 billion

2018[107] 3

$12.68 billion

1

$17.4 billion

2019[108][11] 2

$13.81 billion

1

$14.8 billion

2020[16] 1

$28.89 billion

2021[7] 1

$31.06 billion

Legend Icon Description

Has not changed from the previous year

Has increased from the previous year

Has decreased from the previous year Philanthropy[edit source]

In a 2006 Business Review Weekly article reviewing the way Australia’s rich support philanthropy, it was noted that Rinehart prefers to keep a low profile, partly to avoid being “harassed by other charities” and partly for reasons of privacy.[109] Rinehart is publicly known for visiting girls’ orphanages in Cambodia[110] and is on the expert advisory board of SISHA, a Cambodian non-profit organisation campaigning against human trafficking,[111][112][non-primary source needed] in particular by rescuing and assisting sexually exploited women and children.[113]

In 2012 Swimming Australia announced a $10 million funding arrangement over 4 years with the Georgina Hope Foundation in conjunction with Hancock Prospecting.[114] The deal supports the Australian Swim Team through direct payments to elite and targeted development swimmers, as well supporting lesser known sports such as synchronised swimming.[115] The arrangement was renewed for a further 2 years in August 2015[116] and includes naming rights to various Swimming Australia events, including the Australian Swimming Championships.[117] As recently as 2019, the sporting group described Rinehart as “part of [the] team” and “part of the swimming family.”.[118] In 2016 Rinehart also began to sponsor the Australian Rowing Team with a significant investment to improve direct financial athlete assistance for the Rio Olympic Games as well as for the four years, leading into the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. It is understood that the deal now also extends to Paris 2024. This further investment is said to make Rinehart the largest individual donor to Olympic sport in Australian history.

Awards[edit source]

In 2022, Rinehart was appointed as an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in the 2022 Australia Day Honours for “distinguished service to the mining sector, to the community through philanthropic initiatives, and to sport as a patron”.[119]

References[edit source]

- ^ “Home page”. Hancock Prospecting Pty Limited. n.d. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “BRW Rich 200 list 2014: 1. Gina Rinehart”. BRW (A Fairfax Media Publication). Sydney. 26 June 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Master John Langley Hayward Australia’s richest baby”. The Australian Women’s Weekly. National Library of Australia. 11 February 1976. p. 13. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ “Gina Rinehart’s eldest daughter Bianca handed control of family’s $4 billion trust”.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Burrell, Andrew (10 January 2012). “Filial loyalty pays off for Gina Rinehart heir”. The Australian. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ “Bloomberg Billionaires Index: Gina Rinehart”. Bloomberg. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Bailey, Michael; Sprague, Julie-anne (27 May 2021). “The 200 richest people in Australia revealed”. Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Zeveloff, Julie (29 June 2011). “Australian Mining Heiress Gina Rinehart Could Become The World’s Richest Person Within Years”. Business Insider Australia. Pedestrian Group. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Finnegan, William (18 March 2013). “The Miner’s Daughter”. The New Yorker. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ “Top 500 Private Companies: Gina Rinehart’s Hancock Prospecting beats Visy as Australia’s biggest private company”. Australian Financial Review. 6 September 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “2019 Australia’s 50 Richest”. Forbes Asia. January 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- ^ Sprague, Julie-anne (29 October 2020). “Rich List 2020 marks the rise of the ore-ligarchs”. The Australian Financial Review. Nine Publishing. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Bailey, Michael; Sprague, Julianne (29 October 2020). “Rich List 2020: Gina Rinehart is wealthiest person in Australia, followed by Andrew Forrest”. Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Stensholt, John (18 March 2021). “How our biggest names thrived during the pandemic”. The Australian Business Review. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ “The 10 Richest Women in the World 2020”. www.forbes.com. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Bailey, Michael; Sprague, Julie-anne (30 October 2020). “The full list: Australia’s wealthiest 200 revealed”. The Australian Financial Review. Nine Publishing. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Butler, Ben (16 May 2021). “Australia’s biggest landholder is Gina Rinehart, controlling 9.2m hectares”. Guardian Australia. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ YouTube, Supplied (7 October 2021). “‘Facts may not be popular’: Gina Rinehart’s speech to Perth private school draws criticism from leading climate scientist”. ABC News. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ “Family Notices”. The West Australian. 12 February 1954.

- ^ “She helped found a mining empire”. The Australian Women’s Weekly. National Library of Australia. 5 April 1967. p. 2. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Treadgold, Tim (2 February 2011). “Miner’s Daughter”. Forbes: Australia’s 40 Richest. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Murphy, Damien (27 November 2010). “Newsmaker: Gina Rinehart”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Leser, David (1999). The Whites of Their Eyes (paperback). Sydney: Allen & Unwin. pp. 296. ISBN 978-1-86508-114-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Pennells, Steve; Hall, Louise (10 September 2011). “Three siblings revealed in Rinehart court feud”. The West Australian. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ Burrell, Andrew (27 November 2010). “The Rinehart not afraid to get her hands dirty”. The Australian. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Australia & New Zealand’s 40 Richest: #14 Gina Rinehart”. Forbes. 2 February 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ “Geographic Name Approvals in Western Australia”. 15 (3). July–September 1999: 7.

- ^ “Geographic Name Approvals in Western Australia”. 15 (4). October–December 1999: 7.

- ^ Ferguson, Adele (2012). Gina Rinehart. Sydney: Pan MacMillan. p. 400. ISBN 978-1-74261-097-9. Archived from the original (paperback) on 3 July 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Garvey, Paul (20 May 2014). “Gina Rinehart misses wedding of son John Hancock”. The Australian. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ Spooner, Rania (30 January 2012). “Another Rinehart daughter exits Hancock board”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ “Rinehart eyes dynasty succession”. Business Spectator. Australian Associated Press. 10 January 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Lynch, Jared (2 March 2015). “Gina Rinehart sues Nine Entertainment over Hancock drama ‘falsehoods’”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ “Meet Our Team”. Hancock Prospecting PTY LTD. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Bryant, Nick (2014). The Rise and Fall of Australia: How a great nation lost its way. North Sydney: Bantam. p. 222. ISBN 9780857983787.

- ^ Jump up to:a b McIntyre, David (26 May 2011). “Newsmaker: Gina Rinehart”. news.com.au. Australian Associated Press. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ Hernandez, Vittorio (10 January 2012). “The Ascent of Ginia Rinehart to the Family Business Empire”. International Business Times. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Chessell, James (18 January 2012). “POSCO lifts stake in Hancock’s Roy Hill” (PDF). Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Klinger, Peter (19 January 2012). “Ratings agencies endorse Roy Hill” (PDF). West Australian. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ “Gina Rinehart buys stake in Ten”. The Age. Australia. 22 November 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ Durie, John (1 February 2012). “Share raid makes Gina Rinehart biggest stakeholder in Fairfax”. The Australian. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ Simper, Errol (6 February 2012). “Gina Rinehart’s Fairfax interest won’t give her control of mining tax debate”. The Australian. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ “Australia’s media black night”. The Economist. 30 June 2012. p. 33.

- ^ Simpson, Kirsty (18 June 2012). “Rinehart steps up Fairfax board battle”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ “No deal: Fairfax won’t offer Gina Rinehart a board seat”. Media Spy. 27 June 2012. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ Ferguson, Adele (8 February 2015). “Rinehart’s exit from Fairfax merely a matter of waning interest”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ Thompson, Sarah, Anthony Macdonald, Jake Mitchell (6 February 2015). “Gina Rinehart sells out of Fairfax Media”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ “The World’s 100 Most Powerful Women”. Forbes. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ “#37 Gina Rinehart”. The World’s 100 Most Powerful Women. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Gina Rinehart buys iconic Kimberley cattle station Fossil Downs”. ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 27 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ Belinda Varischetti (27 July 2015). “Gina Rinehart out-bids ‘unprecedented’ global and domestic interest in Fossil Downs Station: estate agent”. ABC Rural. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ “Gina Rinehart’s Roy Hill mine to ship iron ore”. Smart Company. 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ “Gina Hancock: Australia’s iron-ore heiress … cool, quiet girl with the power to move mountains”, Woman’s Day, 16 June 1975

- ^ “Singo & Gina”, The Monthly, November 2012.

- ^ “Far from loopy, Rinehart espouses standard economic and liberal theory”, The Australian, 7 September 2012

- ^ Hewett, Jennifer (1 June 2010). “Gina Rinehart joins anti-tax chorus”. The Australian. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ “About ANDEV”. Australians for Northern Development & Economic Vision. 2011. Archived from the original on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Manne, Robert (8 February 2012). “Lord Monckton and the Future of Australian Media”. The Monthly. Australia. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ “The Lord Monckton roadshow” (transcript). Background Briefing. Australia: ABC Radio. 19 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Rinehart, Gina (2012). Northern Australia and then some: Changes we need to make our country rich. Executive Media Pty Ltd. ISBN 9781921345258.

- ^ Creighton, Adam (6 April 2013). “Southern red tape hobbles Top End’s great leap forward”. The Australian. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ “Gina Rinehart tells whingers: Get out of the pub”. The Courier Mail. 30 August 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rinehart, Gina (23 August 2012). “Gina Rinehart”. Sydney Mining Club – via YouTube.

- ^ Kennedy, Duncan (5 September 2012). “Gina Rinehart calls for Australian wage cut”. BBC.

- ^ Memmott, Mark (5 September 2012). “Billionaire Slammed After Musing About Workers Paid $2 A Day”. NPR.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hall, Louise; Pennells, Steve (8 October 2011). “Rinehart’s children win first round”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Bianca Rinehart Gets Control of Hope Margaret Hancock Trust”. The Wall Street Journal. 28 May 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Shanahan, Leo (13 March 2012). “My kids are not up to it: Gina Rinehart”. The Australian. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Dale, Amy (13 March 2012). “Australia’s richest woman Gina Rinehart accused of offering her eldest daughter money to drop legal action”. Herald Sun. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ Pennells, Steve; Hall, Louise (9 September 2011). “Gina Rinehart sued by daughter”. The West Australian. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ^ Shanahan, Leo; Burrell, Andrew (9 September 2011). “Another family feud for Gina Rinehart”. The Australian. Australian Associated Press. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ^ Shanahan, Leo (14 September 2011). “Rinehart gags media on family trust fund dispute”. The Australian. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Madden, James (8 October 2011). “Gina Rinehart’s children in bid to oust their mother”. The Australian. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ Hall, Louise (14 January 2012). “Airing of dirty linen to come in three weeks”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Hall, Louise (2 February 2012). “Family feud details to stay secret for at least five more weeks”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Robinson, Natasha (2 February 2012). “Gina Rinehart’s safety ‘at risk’, court told in suppression bid”. The Australian. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Dale, Amy (13 March 2012). “Days away from being billionaires, Gina Rinehart locks trust for half a century”. The Daily Telegraph. Australia. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ Ferguson, Adele (12 October 2013). “Family feud over matters of trust”. The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Shanahan, Leo (2 October 2013). “Gina Rinehart exits bitter family row over trust”. The Australian. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ferguson, Adele (28 May 2015). “Gina Rinehart’s precarious position atop the BRW Rich 200 list”. BRW. Sydney. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ Ferguson, Adele (4 June 2012). “Rinehart world’s richest woman”. BRW. Sydney. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Rinehart Doubles Fortune as Asia Pacific’s Richest, Forbes Says”. Business Week. Bloomsberg. 2 February 2012. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Woodhead, Ben (5 March 2013). “Rinehart 36th richest, as Forbes names world’s billionaires”. Financial Review. Australia. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Treadgold, Tim (21 March 2014). “Australia’s $17 Billion Woman on the Road To Becoming A Whole Lot Richer”. Forbes. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Peterson-Withorn, Chase (4 March 2015). “Forbes Billionaires 2015: See Who Lost The Most Money”. Forbes. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ “Australia’s 50 Richest People: 2016 Ranking”. Forbes Asia. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Treadgold, Tim (22 June 2011). “Why Gina Rinehart is on her way to being the world’s richest: Treadgold”. SmartCompany. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ “Australian woman predicted to become world’s richest person”. The Telegraph. United Kingdom. 27 June 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Thomson, James (19 January 2012). “Gina Rinehart’s now worth $20 billion and her hard work’s just started”. SmartCompany. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Burrell, Andrew (21 January 2012). “Stakes raised as Posco play makes Rinehart a $20bn woman”. The Australian. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ “The World’s Billionaires: #48: Gina Rinehart”. Forbes. March 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ Murphy, Damien (24 May 2012). “Rinehart world’s richest woman as wealth triples in a year”. The Age. Australia. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ “Australia’s Gina Rinehart is ‘world’s richest woman’”. BBC News. 24 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ “Bloomberg Billionaires Index”. Bloomberg LP. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “BRW rich list topped by Harry Triguboff, Gina Rinehart slips to fourth”. ABC News. 26 May 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ “James Packer still top of rich list”. The Sydney Morning Herald. 30 May 2007.

- ^ Litras, Peter (28 May 2008). “Rich surprise: Alan Bond bounces back”. The Age. Melbourne. Australian Associated Press. Archived from the original on 1 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Thomson, James (20 March 2008). “Australia and New Zealand’s 40 Richest: The List”. Forbes Asia. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Zappone, Chris (27 May 2009). “Rich get poorer”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ “Australia’s 40 Richest: Gina Rinehart”. Forbes Asia. 13 May 2009. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ “Gina Rinehart tops Australian rich list”. The Age. Australia. 3 February 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Jackson, Sally (23 May 2012). “The $29.17 billion woman: Gina Rinehart tops BRW’s Rich List”. The Australian. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ Colquhoun, Steve; Heathcote, Andrew (22 May 2013). “Rinehart drops more than Lowy’s entire worth”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ “BRW Rich 200 list 2015: 1. Gina Rinehart”. BRW (A Fairfax Media Publication). Sydney. May 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ Stensholt, John (28 May 2015). “Down $6b but Gina Rinehart remains richest Australian in BRW Rich 200”. Business Review Weekly. Australia. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ Stensholt, John, ed. (25 May 2017). “Financial Review Rich List 2017”. Financial Review. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Stensholt, John (25 May 2018). “2018 AFR Rich List: Who are Australia’s richest people?”. The Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ Bailey, Michael (30 May 2019). “Australia’s 200 richest people revealed”. The Australian Financial Review. Nine Publishing. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Ferguson, Adele (29 June – 5 July 2006). “Not Enough” (PDF). Business Review Weekly. Melbourne. p. 30. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ Kerr, Peter (25 May 2011). “First lady”. Business Review Weekly. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ “In October 2010, SISHA launched our new Hope Scholarship Award Program”. SISHA. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ “Georgina Rinehart flies to Cambodia to visit SISHA!”. Facebook. 14 December 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ Hewett, Jennifer (4 February 2012). “Rinehart: reclusive, driven entrepreneur, but a mining pioneer at heart”. The Weekend Australian. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ “Rinehart pours $10m into Swimming Aust”. The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ “Without Gina Rinehart we would be stuck in London slump, says John Bertrand”. The Sydney Morning Herald. 17 August 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ “Swimming Australia mines massive sponsorship deal with Hancock Prospecting”. The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 March 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ “Calendar”. Swimming Australia. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ “Aussie swimmer’s protest at Chinese rival is awkward for Gina Rinehart”. Australian Financial Review. 22 July 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ “Australia Day 2022 Honours List”. Sydney Morning Herald. Nine Entertainment Co. 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

Further reading[edit source]

- Bryant, Nick (May 2012). “What Gina Wants: Gina Rinehart’s quest for respect and gratitude”. The Monthly. Australia. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- Cadzow, Jane (21 January 2012). “The iron lady”. The Age. Australia. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- Finnegan, William (25 March 2013). “The miner’s daughter : Gina Rinehart is Australia’s richest–and most controversial–billionaire”. The New Yorker. Vol. 89, no. 6. pp. 76–87. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- Ferguson, Adele (26 June 2012). Gina Rinehart: The Untold Story of the Richest Woman in the World. Sydney: Macmillan Australia. ISBN 9781742610979. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Marshall, Debi (2012). The House of Hancock: The Rise and Rise of Gina Rinehart. Sydney: William Heinemann Australia. ISBN 9781742756745.

- Newton, Gloria (19 February 1975). “Lang Hancock’s daughter comes of age”. The Australian Women’s Weekly. National Library of Australia. p. 10. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

External links[edit source]

- Video portrait on ABC’s Hungry Beast [content blocked outside Australia.]

- Rinehart, Gina (1954–) in The Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia

-

George Soros

George Soros[a] HonFBA (born György Schwartz, August 12, 1930)[1][2] is a Hungarian-born American[b] billionaire investor and philanthropist.[8][9] As of March 2021, he had a net worth of US$8.6 billion,[10][11] having donated more than $32 billion to the Open Society Foundations,[12] of which $15 billion have already been distributed, representing 64% of his original fortune. Forbes called him the “most generous giver” (in terms of percentage of net worth).[13]

Born in Budapest to a non-observant Jewish family, Soros survived the Nazi occupation of Hungary and moved to the United Kingdom in 1947. He studied at the London School of Economics and was awarded a BSc in philosophy in 1951, and then a Master of Science degree, also in philosophy, in 1954.[4][14][15]

Soros began his business career by taking various jobs at merchant banks in the United Kingdom and then the United States, before starting his first hedge fund, Double Eagle, in 1969. Profits from his first fund furnished the seed money to start Soros Fund Management, his second hedge fund, in 1970. Double Eagle was renamed to Quantum Fund and was the principal firm Soros advised. At its founding, Quantum Fund had $12 million in assets under management, and as of 2011 it had $25 billion, the majority of Soros’s overall net worth.[16]

Soros is known as “The Man Who Broke the Bank of England” because of his short sale of US$10 billion worth of pounds sterling, which made him a profit of $1 billion during the 1992 Black Wednesday UK currency crisis.[17] Based on his early studies of philosophy, Soros formulated the General Theory of Reflexivity for capital markets, which he says renders a clear picture of asset bubbles and fundamental/market value of securities, as well as value discrepancies used for shorting and swapping stocks.[18]

Soros is a supporter of progressive and liberal political causes, to which he dispenses donations through his foundation, the Open Society Foundations.[19] Between 1979 and 2011, he donated more than $11 billion to various philanthropic causes;[20][21] by 2017, his donations “on civil initiatives to reduce poverty and increase transparency, and on scholarships and universities around the world” totaled $12 billion.[22] He influenced the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s and early 1990s,[23] and provided one of Europe’s largest higher education endowments to the Central European University in his Hungarian hometown.[24]

His extensive funding of political causes has made him a “bugaboo of European nationalists“.[25] The New York Times reported in October 2018 that “conspiracy theories about him have gone mainstream, to nearly every corner of the Republican Party“.[26] Numerous American conservatives have promoted false claims that characterize Soros as a singularly dangerous “puppet master” behind many alleged global plots.[26][27][28][29] Conspiracy theories targeting Soros, who is of Jewish descent, have often been described as antisemitic.[30][31][32]

Contents

- 1Early life and education

- 2Investment career

- 3Personal life

- 4Political involvement

- 5Conspiracy theories and threats

- 6Political and economic views

- 7Wealth and philanthropy

- 8Honors and awards

- 9Publications and scholarship

- 10See also

- 11Notes

- 12References

- 13Further reading

- 14External links

Early life and education[edit source]

Soros was born in Budapest in the Kingdom of Hungary to a prosperous non-observant Jewish family, who, like many upper-middle class Hungarian Jews at the time, were uncomfortable with their roots. Soros has wryly described his home as a Jewish antisemitic home.[33] His mother Erzsébet (also known as Elizabeth) came from a family that owned a thriving silk shop. His father Tivadar (also known as Teodoro Ŝvarc) was a lawyer[34] and a well-known Esperanto-speaker who edited the Esperanto literary magazine Literatura Mondo and raised his son to speak the language.[35] Tivadar had also been a prisoner of war during and after World War I until he escaped from Russia and rejoined his family in Budapest.[36][37] The two married in 1924. In 1936, Soros’s family changed their name from the German-Jewish Schwartz to Soros, as protective camouflage in increasingly antisemitic Hungary.[38][39] Tivadar liked the new name because it is a palindrome and because of its meaning. In Hungarian, soros means “next in line,” or “designated successor”; in Esperanto it means “will soar.”[40][41][42]

Soros was 13 years old in March 1944 when Nazi Germany occupied Hungary.[43] The Nazis barred Jewish children from attending school, and Soros and the other schoolchildren were made to report to the Judenrat (“Jewish Council”), which had been established during the occupation. Soros later described this time to writer Michael Lewis: “The Jewish Council asked the little kids to hand out the deportation notices. I was told to go to the Jewish Council. And there I was given these small slips of paper … I took this piece of paper to my father. He instantly recognized it. This was a list of Hungarian Jewish lawyers. He said, ‘You deliver the slips of paper and tell the people that if they report they will be deported.”[44][45]

Soros did not return to that job; his family survived the war by purchasing documents to say that they were Christians. Later that year at age 14, Soros posed as the Christian godson of an official of the collaborationist Hungarian government’s Ministry of Agriculture, who himself had a Jewish wife in hiding. On one occasion, rather than leave the 14-year-old alone, the official took Soros with him while completing an inventory of a Jewish family’s confiscated estate. Tivadar saved not only his immediate family but also many other Hungarian Jews, and Soros later wrote that 1944 had been “the happiest [year] of his life,” for it had given him the opportunity to witness his father’s heroism.[46][47] In 1945, Soros survived the Siege of Budapest, in which Soviet and German forces fought house-to-house through the city. George and his mother also spent some time hiding with the family of Elza Brandeisz and even attended their Lutheran church with them.[48]

In 1947, Soros moved to England and became a student at the London School of Economics.[49] While a student of the philosopher Karl Popper, Soros worked as a railway porter and as a waiter, and once received £40 from a Quaker charity.[50] Soros would sometimes stand at Speakers’ Corner lecturing about the virtues of internationalism in Esperanto, which he had learned from his father.[51]

From the London School of Economics, Soros graduated as a Bachelor of Science in philosophy in 1951, and a Master of Science in philosophy in 1954.[4]

Investment career[edit source]

Early business experience[edit source]

In a discussion at the Los Angeles World Affairs Council in 2006, Alvin Shuster, former foreign editor of the Los Angeles Times, asked Soros, “How does one go from an immigrant to a financier? … When did you realize that you knew how to make money?” Soros replied, “Well, I had a variety of jobs and I ended up selling fancy goods on the seaside, souvenir shops, and I thought, that’s really not what I was cut out to do. So, I wrote to every managing director in every merchant bank in London, got just one or two replies, and eventually that’s how I got a job in a merchant bank.”[52]

Singer and Friedlander[edit source]

In 1954, Soros began his financial career at the merchant bank Singer & Friedlander of London. He worked as a clerk and later moved to the arbitrage department. A fellow employee, Robert Mayer, suggested he apply at his father’s brokerage house, F.M. Mayer of New York.[53]

F. M. Mayer[edit source]

In 1956, Soros moved to New York City, where he worked as an arbitrage trader for F. M. Mayer (1956–59). He specialized in European stocks, which were becoming popular with U.S. institutional investors following the formation of the Coal and Steel Community, which later became the Common Market.[54]

Wertheim and Co.[edit source]

In 1959, after three years at F. M. Mayer, Soros moved to Wertheim & Co. He planned to stay for five years, enough time to save $500,000, after which he intended to return to England to study philosophy.[55] He worked as an analyst of European securities until 1963.

During this period, Soros developed the theory of reflexivity to extend the ideas of his tutor at the London School of Economics, Karl Popper. Reflexivity posits that market values are often driven by the fallible ideas of participants, not only by the economic fundamentals of the situation. Ideas and events influence each other in reflexive feedback loops. Soros argued that this process leads to markets having procyclical “virtuous” or “vicious” cycles of boom and bust, in contrast to the equilibrium predictions of more standard neoclassical economics.[56][57]

Arnhold and S. Bleichroeder[edit source]

From 1963 to 1973, Soros’s experience as a vice president at Arnhold and S. Bleichroeder resulted in little enthusiasm for the job; business was slack following the introduction of the Interest Equalization Tax, which undermined the viability of Soros’s European trading. He spent the years from 1963 to 1966 with his main focus on the revision of his philosophy dissertation. In 1966 he started a fund with $100,000 of the firm’s money to experiment with his trading strategies.

In 1969, Soros set up the Double Eagle hedge fund with $4m of investors’ capital including $250,000 of his own money.[58] It was based in Curaçao, Dutch Antilles.[59] Double Eagle itself was an offshoot of Arnhold and S. Bleichroeder’s First Eagle fund established by Soros and that firm’s chairman Henry H. Arnhold in 1967.[60][61]

In 1973, the Double Eagle Fund had $12 million and formed the basis of the Soros Fund. George Soros and Jim Rogers received returns on their share of capital and 20 percent of the profits each year.[54]

Soros Fund Management[edit source]

In 1970, Soros founded Soros Fund Management and became its chairman. Among those who held senior positions there at various times were Jim Rogers, Stanley Druckenmiller, Mark Schwartz, Keith Anderson, and Soros’s two sons.[62][63][64]

In 1973, due to perceived conflicts of interest limiting his ability to run the two funds, Soros resigned from the management of the Double Eagle Fund. He then established the Soros Fund and gave investors in the Double Eagle Fund the option of transferring to that or staying with Arnhold and S. Bleichroeder.

It was later renamed the Quantum Fund, after the physical theory of quantum mechanics. By that time the value of the fund had grown to $12m, only a small proportion of which was Soros’s own money. He and Jim Rogers reinvested their returns from the fund, and also a large part of their 20% performance fees, thereby expanding their stake.[53]

By 1981, the fund had grown to $400m, and then a 22% loss in that year and substantial redemptions by some of the investors reduced it to $200m.[65]

In July 2011, Soros announced that he had returned funds from outside investors’ money (valued at $1 billion) and instead invested funds from his $24.5 billion family fortune, due to changes in U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission disclosure rules, which he felt would compromise his duties of confidentiality to his investors. The fund had at that time averaged over 20% per year compound returns.[66]

In 2013, the Quantum Fund made $5.5 billion, making it again the most successful hedge fund in history. Since its inception in 1973, the fund has generated $40 billion.[67]

The fund announced in 2015 that it would inject $300 million to help finance the expansion of Fen Hotels, an Argentine hotel company. The funds will develop 5,000 rooms over the next three years throughout various Latin American countries.[68]

Economic crisis in the 1990s and 2000s[edit source]

George Soros during a session on redesigning the international monetary system at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2011.

Soros had been building a huge short position in pounds sterling for months leading up to the Black Wednesday of September 1992. Soros had recognized the unfavorable position of the United Kingdom in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. For Soros, the rate at which the United Kingdom was brought into the European Exchange Rate Mechanism was too high, their inflation was also much too high (triple the German rate), and British interest rates were hurting their asset prices.[69]

By September 16, 1992, the day of Black Wednesday, Soros’s fund had sold short more than $10 billion in pounds,[62] profiting from the UK government’s reluctance to either raise its interest rates to levels comparable to those of other European Exchange Rate Mechanism countries or float its currency.