-

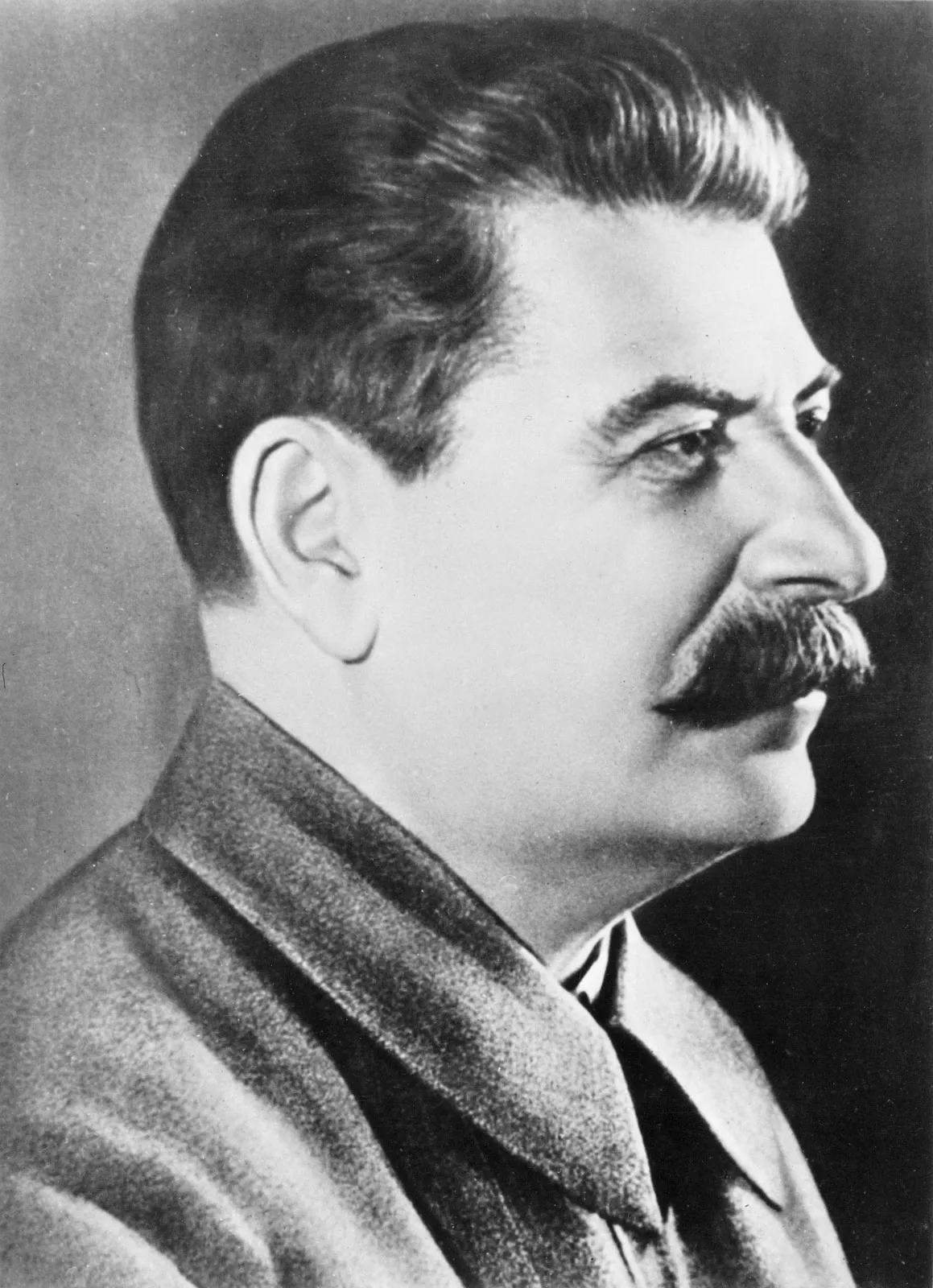

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin[f] (18 December [O.S. 6 December] 1878[1] – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who governed the Soviet Union from 1922 until his death in 1953. He held power both as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1922–1952) and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union (1941–1953). Despite initially governing the country as part of a collective leadership, he ultimately consolidated power to become the Soviet Union’s dictator by the 1930s. A communist ideologically committed to the Leninist interpretation of Marxism, Stalin formalised these ideas as Marxism–Leninism while his own policies are known as Stalinism.

Born to a poor family in Gori in the Russian Empire (now Georgia), Stalin attended the Tbilisi Spiritual Seminary before eventually joining the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. He went on to edit the party’s newspaper, Pravda, and raised funds for Vladimir Lenin‘s Bolshevik faction via robberies, kidnappings and protection rackets. Repeatedly arrested, he underwent several internal exiles. After the Bolsheviks seized power during the October Revolution and created a one-party state under the newly formed Communist Party in 1917, Stalin joined its governing Politburo. Serving in the Russian Civil War before overseeing the Soviet Union’s establishment in 1922, Stalin assumed leadership over the country following Lenin’s death in 1924. Under Stalin, socialism in one country became a central tenet of the party’s dogma. As a result of the Five-Year Plans implemented under his leadership, the country underwent agricultural collectivisation and rapid industrialisation, creating a centralised command economy. This led to severe disruptions of food production that contributed to the famine of 1932–33. To eradicate accused “enemies of the working class“, Stalin instituted the Great Purge, in which over a million were imprisoned and at least 700,000 executed between 1934 and 1939. By 1937, he had absolute control over the party and government.

Stalin promoted Marxism–Leninism abroad through the Communist International and supported European anti-fascist movements during the 1930s, particularly in the Spanish Civil War. In 1939, his regime signed a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, resulting in the Soviet invasion of Poland. Germany ended the pact by invading the Soviet Union in 1941. Despite initial setbacks, the Soviet Red Army repelled the German invasion and captured Berlin in 1945, thereby ending World War II in Europe. Amid the war, the Soviets annexed the Baltic states and then established Soviet-aligned governments throughout Central and Eastern Europe, China, and North Korea. The Soviet Union and the United States emerged as global superpowers and entered a period of tensions, the Cold War. Stalin presided over the Soviet post-war reconstruction and its development of an atomic bomb in 1949. During these years, the country experienced another major famine and an antisemitic campaign that culminated in the doctors’ plot. After Stalin’s death in 1953, he was eventually succeeded by Nikita Khrushchev, who subsequently denounced his rule and initiated the de-Stalinisation of Soviet society.

Widely considered to be one of the 20th century’s most significant figures, Stalin was the subject of a pervasive personality cult within the international Marxist–Leninist movement, which revered him as a champion of the working class and socialism. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Stalin has retained popularity in Russia and Georgia as a victorious wartime leader who cemented the Soviet Union’s status as a leading world power. Conversely, his regime has been described as totalitarian, and has been widely condemned for overseeing mass repression, ethnic cleansing, wide-scale deportation, hundreds of thousands of executions, and famines that killed millions.

Contents

- 1Early life

- 2In Lenin’s government

- 3Consolidation of power

- 4World War II

- 5Post-war era

- 6Political ideology

- 7Personal life and characteristics

- 8Legacy

- 9See also

- 10Notes

- 11References

- 12Further reading

- 13External links

Early life[edit source]

Main article: Early life of Joseph Stalin

Childhood to young adulthood: 1878–1899[edit source]

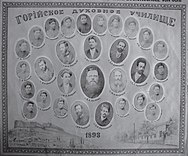

1893 class table of Gori Religious School including a photo of Stalin. Some of the photos may be from earlier dates, but it is believed that this photo of Stalin was taken in 1893.

Stalin’s birth name was Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili.[d] He was born in the Georgian town of Gori,[2] then part of the Tiflis Governorate of the Russian Empire and home to a mix of Georgian, Armenian, Russian, and Jewish communities.[3] He was born on 18 December [O.S. 6 December] 1878[4][g] and baptised on 29 December.[6] His parents, Besarion Jughashvili and Ekaterine Geladze,[7] were ethnically Georgian, and Stalin grew up speaking the Georgian language.[8] He was their only child to survive past infancy[9] and was nicknamed “Soso”, a diminutive of “Ioseb”.[10]

Besarion was a shoemaker who was employed in a workshop owned by another man;[11] it was initially a financial success but later fell into decline,[12] and the family found itself living in poverty.[13] Besarion became an alcoholic[14] and drunkenly beat his wife and son.[15] Ekaterine and Stalin left the home by 1883 and began a wandering life, moving through nine different rented rooms over the next decade.[16] In 1886, they moved into the house of a family friend, Father Christopher Charkviani.[17] Ekaterine worked as a house cleaner and launderer and was determined to send her son to school.[18] In September 1888, Stalin enrolled at the Gori Church School, a place secured by Charkviani.[19] Although he got into many fights,[20] Stalin excelled academically,[21] displaying talent in painting and drama classes,[22] writing his own poetry,[23] and singing as a choirboy.[24] Stalin faced several severe health problems: An 1884 smallpox infection left him with facial scars;[25] and at age 12 he was seriously injured when he was hit by a phaeton, likely the cause of a lifelong disability in his left arm.[26]In 1894 Stalin began his studies at the Tiflis Spiritual Seminary (pictured here in the 1870s).

In August 1894, Stalin enrolled in the Orthodox Spiritual Seminary in Tiflis, enabled by a scholarship that allowed him to study at a reduced rate.[27] He joined 600 trainee priests who boarded there,[28] and he achieved high grades.[29] He continued writing poetry; five of his poems, on themes such as nature, land and patriotism, were published under the pseudonym of “Soselo” in Ilia Chavchavadze‘s newspaper Iveria (Georgia).[30] According to Stalin’s biographer Simon Sebag Montefiore, they became “minor Georgian classics”[31] and were included in various anthologies of Georgian poetry over the coming years.[31] As he grew older, Stalin lost interest in priestly studies, his grades dropped,[32] and he was repeatedly confined to a cell for his rebellious behaviour.[33] The seminary’s journal noted that he declared himself an atheist, stalked out of prayers and refused to doff his hat to monks.[34]

Stalin joined a forbidden book club at the school;[35] he was particularly influenced by Nikolay Chernyshevsky‘s 1863 pro-revolutionary novel What Is To Be Done?[36] Another influential text was Alexander Kazbegi‘s The Patricide, with Stalin adopting the nickname “Koba” from that of the book’s bandit protagonist.[37] He also read Capital, the 1867 book by German sociological theorist Karl Marx.[38] Stalin devoted himself to Marx’s socio-political theory, Marxism,[39] which was then on the rise in Georgia, one of various forms of socialism opposed to the empire’s governing tsarist authorities.[40] At night, he attended secret workers’ meetings[41] and was introduced to Silibistro “Silva” Jibladze, the Marxist founder of Mesame Dasi (“Third Group”), a Georgian socialist group.[42] Stalin left the seminary in April 1899 and never returned.[43]

Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party: 1899–1904[edit source]

Police photograph of Stalin, taken in 1902, when he was 23 years old.

In October 1899, Stalin began work as a meteorologist at the Tiflis observatory.[44] He attracted a group of supporters through his classes in socialist theory[45] and co-organised a secret workers’ mass meeting for May Day 1900,[46] at which he successfully encouraged many of the men to take strike action.[47] By this point, the empire’s secret police, the Okhrana, were aware of Stalin’s activities in Tiflis’ revolutionary milieu.[47] They attempted to arrest him in March 1901, but he escaped and went into hiding,[48] living off the donations of friends and sympathisers.[49] Remaining underground, he helped plan a demonstration for May Day 1901, in which 3,000 marchers clashed with the authorities.[50] He continued to evade arrest by using aliases and sleeping in different apartments.[51] In November 1901, he was elected to the Tiflis Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), a Marxist party founded in 1898.[52]

That month, Stalin travelled to the port city of Batumi.[53] His militant rhetoric proved divisive among the city’s Marxists, some of whom suspected that he might be an agent provocateur working for the government.[54] He found employment at the Rothschild refinery storehouse, where he co-organised two workers’ strikes.[55] After several strike leaders were arrested, he co-organised a mass public demonstration which led to the storming of the prison; troops fired upon the demonstrators, 13 of whom were killed.[56] Stalin organised another mass demonstration on the day of their funeral,[57] before being arrested in April 1902.[58] Held first in Batumi Prison[59] and then Kutaisi Prison,[60] in mid-1903 he was sentenced to three years of exile in eastern Siberia.[61]

Stalin left Batumi in October, arriving at the small Siberian town of Novaya Uda in late November 1903.[62] There, he lived in a two-room peasant’s house, sleeping in the building’s larder.[63] He made two escape attempts: On the first, he made it to Balagansk before returning due to frostbite.[64] His second attempt, in January 1904, was successful and he made it to Tiflis.[65] There, he co-edited a Georgian Marxist newspaper, Proletariatis Brdzola (“Proletarian Struggle”), with Philip Makharadze.[66] He called for the Georgian Marxist movement to split from its Russian counterpart, resulting in several RSDLP members accusing him of holding views contrary to the ethos of Marxist internationalism and calling for his expulsion from the party; he soon recanted his opinions.[67] During his exile, the RSDLP had split between Vladimir Lenin‘s “Bolsheviks” and Julius Martov‘s “Mensheviks“.[68] Stalin detested many of the Mensheviks in Georgia and aligned himself with the Bolsheviks.[69] Although he established a Bolshevik stronghold in the mining town of Chiatura,[70] Bolshevism remained a minority force in the Menshevik-dominated Georgian revolutionary scene.[71]

Revolution of 1905 and its aftermath: 1905–1912[edit source]

Stalin first met Vladimir Lenin at a 1905 conference in Tampere. Lenin became “Stalin’s indispensable mentor”.[72]

In January 1905, government troops massacred protesters in Saint Petersburg. Unrest soon spread across the Russian Empire in what came to be known as the Revolution of 1905.[73] Georgia was particularly affected.[74] Stalin was in Baku in February when ethnic violence broke out between Armenians and Azeris; at least 2,000 were killed.[75] He publicly lambasted the “pogroms against Jews and Armenians” as being part of Tsar Nicholas II‘s attempts to “buttress his despicable throne”.[76] Stalin formed a Bolshevik Battle Squad which he used to try to keep Baku’s warring ethnic factions apart; he also used the unrest as a cover for stealing printing equipment.[76] Amid the growing violence throughout Georgia he formed further Battle Squads, with the Mensheviks doing the same.[77] Stalin’s squads disarmed local police and troops,[78] raided government arsenals,[79] and raised funds through protection rackets on large local businesses and mines.[80] They launched attacks on the government’s Cossack troops and pro-Tsarist Black Hundreds,[81] co-ordinating some of their operations with the Menshevik militia.[82]

In November 1905, the Georgian Bolsheviks elected Stalin as one of their delegates to a Bolshevik conference in Saint Petersburg.[83] On arrival, he met Lenin’s wife Nadezhda Krupskaya, who informed him that the venue had been moved to Tampere in the Grand Duchy of Finland.[84] At the conference Stalin met Lenin for the first time.[85] Although Stalin held Lenin in deep respect, he was vocal in his disagreement with Lenin’s view that the Bolsheviks should field candidates for the forthcoming election to the State Duma; Stalin saw the parliamentary process as a waste of time.[86] In April 1906, Stalin attended the RSDLP Fourth Congress in Stockholm; this was his first trip outside the Russian Empire.[87] At the conference, the RSDLP — then led by its Menshevik majority — agreed that it would not raise funds using armed robbery.[88] Lenin and Stalin disagreed with this decision[89] and later privately discussed how they could continue the robberies for the Bolshevik cause.[90]

Stalin married Kato Svanidze in a church ceremony at Senaki in July 1906.[91] In March 1907 she bore a son, Yakov.[92] By that year — according to the historian Robert Service — Stalin had established himself as “Georgia’s leading Bolshevik”.[93] He attended the Fifth RSDLP Congress, held in London in May–June 1907.[94] After returning to Tiflis, Stalin organised the robbing of a large delivery of money to the Imperial Bank in June 1907. His gang ambushed the armed convoy in Yerevan Square with gunfire and home-made bombs. Around 40 people were killed, but all of his gang escaped alive.[95] After the heist, Stalin settled in Baku with his wife and son.[96] There, Mensheviks confronted Stalin about the robbery and voted to expel him from the RSDLP, but he took no notice of them.[97]A mugshot of Stalin made in 1911 by the Tsarist secret police.

In Baku, Stalin secured Bolshevik domination of the local RSDLP branch[98] and edited two Bolshevik newspapers, Bakinsky Proletary and Gudok (“Whistle”).[99] In August 1907, he attended the Seventh Congress of the Second International — an international socialist organisation — in Stuttgart, Germany.[100] In November 1907, his wife died of typhus,[101] and he left his son with her family in Tiflis.[102] In Baku he had reassembled his gang, the Outfit,[103] which continued to attack Black Hundreds and raised finances by running protection rackets, counterfeiting currency, and carrying out robberies.[104] They also kidnapped the children of several wealthy figures to extract ransom money.[105] In early 1908, he travelled to the Swiss city of Geneva to meet with Lenin and the prominent Russian Marxist Georgi Plekhanov, although the latter exasperated him.[106]

In March 1908, Stalin was arrested and interned in Bailov Prison in Baku.[107] There he led the imprisoned Bolsheviks, organised discussion groups, and ordered the killing of suspected informants.[108] He was eventually sentenced to two years exile in the village of Solvychegodsk, Vologda Province, arriving there in February 1909.[109] In June, he escaped the village and made it to Kotlas disguised as a woman and from there to Saint Petersburg.[110] In March 1910, he was arrested again and sent back to Solvychegodsk.[111] There he had affairs with at least two women; his landlady, Maria Kuzakova, later gave birth to his second son, Konstantin.[112] In June 1911, Stalin was given permission to move to Vologda, where he stayed for two months,[113] having a relationship with Pelageya Onufrieva.[114] He escaped to Saint Petersburg,[115] where he was arrested in September 1911 and sentenced to a further three-year exile in Vologda.[116]

Rise to the Central Committee and editorship of Pravda: 1912–1917[edit source]

The first issue of Pravda, the Bolshevik newspaper of which Stalin was editor

In January 1912, while Stalin was in exile, the first Bolshevik Central Committee was elected at the Prague Conference.[117] Shortly after the conference, Lenin and Grigory Zinoviev decided to co-opt Stalin to the committee.[117] Still in Vologda, Stalin agreed, remaining a Central Committee member for the rest of his life.[118] Lenin believed that Stalin, as a Georgian, would help secure support for the Bolsheviks from the empire’s minority ethnicities.[119] In February 1912, Stalin again escaped to Saint Petersburg,[120] tasked with converting the Bolshevik weekly newspaper, Zvezda (“Star”) into a daily, Pravda (“Truth”).[121] The new newspaper was launched in April 1912,[122] although Stalin’s role as editor was kept secret.[122]

In May 1912, he was arrested again and imprisoned in the Shpalerhy Prison, before being sentenced to three years exile in Siberia.[123] In July, he arrived at the Siberian village of Narym,[124] where he shared a room with a fellow Bolshevik Yakov Sverdlov.[125] After two months, Stalin and Sverdlov escaped back to Saint Petersburg.[126] During a brief period back in Tiflis, Stalin and the Outfit planned the ambush of a mail coach, during which most of the group — although not Stalin — were apprehended by the authorities.[127] Stalin returned to Saint Petersburg, where he continued editing and writing articles for Pravda.[128]Stalin in 1915

After the October 1912 Duma elections, where six Bolsheviks and six Mensheviks were elected, Stalin wrote articles calling for reconciliation between the two Marxist factions, for which Lenin criticised him.[129] In late 1912, Stalin twice crossed into the Austro-Hungarian Empire to visit Lenin in Kraków,[130] eventually bowing to Lenin’s opposition to reunification with the Mensheviks.[131] In January 1913, Stalin travelled to Vienna,[132] where he researched the ‘national question’ of how the Bolsheviks should deal with the Russian Empire’s national and ethnic minorities.[133] Lenin, who encouraged Stalin to write an article on the subject,[134] wanted to attract those groups to the Bolshevik cause by offering them the right of secession from the Russian state, but also hoped they would remain part of a future Bolshevik-governed Russia.[135]

Stalin’s article Marxism and the National Question[136] was first published in the March, April, and May 1913 issues of the Bolshevik journal Prosveshcheniye;[137] Lenin was pleased with it.[138] According to Montefiore, this was “Stalin’s most famous work”.[135] The article was published under the pseudonym “K. Stalin”,[138] a name he had used since 1912.[139] Derived from the Russian word for steel (stal),[140] this has been translated as “Man of Steel”;[141] Stalin may have intended it to imitate Lenin’s pseudonym.[142] Stalin retained the name for the rest of his life, possibly because it was used on the article that established his reputation among the Bolsheviks.[143]

In February 1913, Stalin was arrested while back in Saint Petersburg.[144] He was sentenced to four years exile in Turukhansk, a remote part of Siberia from which escape was particularly difficult.[145] In August, he arrived in the village of Monastyrskoe, although after four weeks was relocated to the hamlet of Kostino.[146] In March 1914, concerned over a potential escape attempt, the authorities moved Stalin to the hamlet of Kureika on the edge of the Arctic Circle.[147] In the hamlet, Stalin had a relationship with Lidia Pereprygia, who was fourteen at the time but within the legal age of consent in Tsarist Russia.[148] In or about December 1914, Pereprygia gave birth to Stalin’s child, although the infant soon died.[149] She gave birth to another of his children, Alexander, circa April 1917.[150][151]

In Kureika, Stalin lived closely with the indigenous Tunguses and Ostyak,[152] and spent much of his time fishing.[153]

Russian Revolution: 1917[edit source]

While Stalin was in exile, Russia entered the First World War, and in October 1916 Stalin and other exiled Bolsheviks were conscripted into the Russian Army, leaving for Monastyrskoe.[154] They arrived in Krasnoyarsk in February 1917,[155] where a medical examiner ruled Stalin unfit for military service because of his crippled arm.[156] Stalin was required to serve four more months on his exile, and he successfully requested that he serve it in nearby Achinsk.[157] Stalin was in the city when the February Revolution took place; uprisings broke out in Petrograd — as Saint Petersburg had been renamed — and Tsar Nicholas II abdicated to escape being violently overthrown. The Russian Empire became a de facto republic, headed by a Provisional Government dominated by liberals.[158] In a celebratory mood, Stalin travelled by train to Petrograd in March.[159] There, Stalin and a fellow Bolshevik Lev Kamenev assumed control of Pravda,[160] and Stalin was appointed the Bolshevik representative to the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, an influential council of the city’s workers.[161] In April, Stalin came third in the Bolshevik elections for the party’s Central Committee; Lenin came first and Zinoviev came second.[162] This reflected his senior standing in the party at the time.[163]

The existing government of landlords and capitalists must be replaced by a new government, a government of workers and peasants.

The existing pseudo-government which was not elected by the people and which is not accountable to the people must be replaced by a government recognised by the people, elected by representatives of the workers, soldiers and peasants and held accountable to their representatives.— Stalin’s editorial in Pravda, October 1917[164]

Stalin helped organise the July Days uprising, an armed display of strength by Bolshevik supporters.[165] After the demonstration was suppressed, the Provisional Government initiated a crackdown on the Bolsheviks, raiding Pravda.[166] During this raid, Stalin smuggled Lenin out of the newspaper’s office and took charge of the Bolshevik leader’s safety, moving him between Petrograd safe houses before smuggling him to Razliv.[167] In Lenin’s absence, Stalin continued editing Pravda and served as acting leader of the Bolsheviks, overseeing the party’s Sixth Congress, which was held covertly.[168] Lenin began calling for the Bolsheviks to seize power by toppling the Provisional Government in a coup d’état. Stalin and a fellow senior Bolshevik Leon Trotsky both endorsed Lenin’s plan of action, but it was initially opposed by Kamenev and other party members.[169] Lenin returned to Petrograd and secured a majority in favour of a coup at a meeting of the Central Committee on 10 October.[170]

On 24 October, police raided the Bolshevik newspaper offices, smashing machinery and presses; Stalin salvaged some of this equipment to continue his activities.[171] In the early hours of 25 October, Stalin joined Lenin in a Central Committee meeting in the Smolny Institute, from where the Bolshevik coup — the October Revolution — was directed.[172] Bolshevik militia seized Petrograd’s electric power station, main post office, state bank, telephone exchange, and several bridges.[173] A Bolshevik-controlled ship, the Aurora, opened fire on the Winter Palace; the Provisional Government’s assembled delegates surrendered and were arrested by the Bolsheviks.[174] Although he had been tasked with briefing the Bolshevik delegates of the Second Congress of Soviets about the developing situation, Stalin’s role in the coup had not been publicly visible.[175] Trotsky and other later Bolshevik opponents of Stalin used this as evidence that his role in the coup had been insignificant, although later historians reject this.[176] According to the historian Oleg Khlevniuk, Stalin “filled an important role [in the October Revolution]… as a senior Bolshevik, member of the party’s Central Committee, and editor of its main newspaper”;[177] the historian Stephen Kotkin similarly noted that Stalin had been “in the thick of events” in the build-up to the coup.[178]

In Lenin’s government[edit source]

Main article: Joseph Stalin during the Russian Revolution, Civil War, and the Polish–Soviet War

Consolidating power: 1917–1918[edit source]

Joseph Stalin in 1917 as a young People’s Commissar.

On 26 October 1917, Lenin declared himself chairman of a new government, the Council of People’s Commissars (“Sovnarkom”).[179] Stalin backed Lenin’s decision not to form a coalition with the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionary Party, although they did form a coalition government with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries.[180] Stalin became part of an informal foursome leading the government, alongside Lenin, Trotsky, and Sverdlov;[181] of these, Sverdlov was regularly absent and died in March 1919.[182] Stalin’s office was based near to Lenin’s in the Smolny Institute,[183] and he and Trotsky were the only individuals allowed access to Lenin’s study without an appointment.[184] Although not so publicly well known as Lenin or Trotsky,[185] Stalin’s importance among the Bolsheviks grew.[186] He co-signed Lenin’s decrees shutting down hostile newspapers,[187] and along with Sverdlov, he chaired the sessions of the committee drafting a constitution for the new Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.[188] He strongly supported Lenin’s formation of the Cheka security service and the subsequent Red Terror that it initiated; noting that state violence had proved an effective tool for capitalist powers, he believed that it would prove the same for the Soviet government.[189] Unlike senior Bolsheviks like Kamenev and Nikolai Bukharin, Stalin never expressed concern about the rapid growth and expansion of the Cheka and Red Terror.[189]The Moscow Kremlin, which Stalin moved into in 1918

Having dropped his editorship of Pravda,[190] Stalin was appointed the People’s Commissar for Nationalities.[191] He took Nadezhda Alliluyeva as his secretary[192] and at some point married her, although the wedding date is unknown.[193] In November 1917, he signed the Decree on Nationality, according ethnic and national minorities living in Russia the right of secession and self-determination.[194] The decree’s purpose was primarily strategic; the Bolsheviks wanted to gain favour among ethnic minorities but hoped that the latter would not actually desire independence.[195] That month, he travelled to Helsinki to talk with the Finnish Social-Democrats, granting Finland’s request for independence in December.[195] His department allocated funds for establishment of presses and schools in the languages of various ethnic minorities.[196] Socialist revolutionaries accused Stalin’s talk of federalism and national self-determination as a front for Sovnarkom’s centralising and imperialist policies.[188]

Because of the ongoing First World War, in which Russia was fighting the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary, Lenin’s government relocated from Petrograd to Moscow in March 1918. Stalin, Trotsky, Sverdlov, and Lenin lived at the Kremlin.[197] Stalin supported Lenin’s desire to sign an armistice with the Central Powers regardless of the cost in territory.[198] Stalin thought it necessary because — unlike Lenin — he was unconvinced that Europe was on the verge of proletarian revolution.[199] Lenin eventually convinced the other senior Bolsheviks of his viewpoint, resulting in signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918.[200] The treaty gave vast areas of land and resources to the Central Powers and angered many in Russia; the Left Socialist Revolutionaries withdrew from the coalition government over the issue.[201] The governing RSDLP party was soon renamed, becoming the Russian Communist Party.[202]

Military Command: 1918–1921[edit source]

After the Bolsheviks seized power, both right and left-wing armies rallied against them, generating the Russian Civil War.[203] To secure access to the dwindling food supply, in May 1918 Sovnarkom sent Stalin to Tsaritsyn to take charge of food procurement in southern Russia.[204] Eager to prove himself as a commander,[205] once there he took control of regional military operations.[206] He befriended two military figures, Kliment Voroshilov and Semyon Budyonny, who would form the nucleus of his military and political support base.[207] Believing that victory was assured by numerical superiority, he sent large numbers of Red Army troops into battle against the region’s anti-Bolshevik White armies, resulting in heavy losses; Lenin was concerned by this costly tactic.[208] In Tsaritsyn, Stalin commanded the local Cheka branch to execute suspected counter-revolutionaries, sometimes without trial[209] and — in contravention of government orders — purged the military and food collection agencies of middle-class specialists, some of whom he also executed.[210] His use of state violence and terror was at a greater scale than most Bolshevik leaders approved of;[211] for instance, he ordered several villages to be torched to ensure compliance with his food procurement program.[212]

In December 1918, Stalin was sent to Perm to lead an inquiry into how Alexander Kolchak‘s White forces had been able to decimate Red troops based there.[213] He returned to Moscow between January and March 1919,[214] before being assigned to the Western Front at Petrograd.[215] When the Red Third Regiment defected, he ordered the public execution of captured defectors.[214] In September he was returned to the Southern Front.[214] During the war, he proved his worth to the Central Committee, displaying decisiveness, determination, and willingness to take on responsibility in conflict situations.[205] At the same time, he disregarded orders and repeatedly threatened to resign when affronted.[216] He was reprimanded by Lenin at the 8th Party Congress for employing tactics which resulted in far too many deaths of Red Army soldiers.[217] In November 1919, the government nonetheless awarded him the Order of the Red Banner for his wartime service.[218]

The Bolsheviks won the Russian civil war by the end of 1919.[219] By that time, Sovnarkom had turned its attention to spreading proletarian revolution abroad, to this end forming the Communist International in March 1919; Stalin attended its inaugural ceremony.[220] Although Stalin did not share Lenin’s belief that Europe’s proletariat were on the verge of revolution, he acknowledged that as long as it stood alone, Soviet Russia remained vulnerable.[221] In December 1918, he drew up decrees recognising Marxist-governed Soviet republics in Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia;[222] during the civil war these Marxist governments were overthrown and the Baltic countries became fully independent of Russia, an act Stalin regarded as illegitimate.[223] In February 1920, he was appointed to head the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate;[224] that same month he was also transferred to the Caucasian Front.[225]Joseph Stalin in 1920.

Following earlier clashes between Polish and Russian troops, the Polish–Soviet War broke out in early 1920, with the Poles invading Ukraine and taking Kyiv on 7 May.[226] On 26 May, Stalin was moved to Ukraine, on the Southwest Front.[227] The Red Army retook Kyiv on 10 June and soon forced the Polish troops back into Poland.[228] On 16 July, the Central Committee decided to take the war into Polish territory.[229] Lenin believed that the Polish proletariat would rise up to support the Russians against Józef Piłsudski‘s Polish government.[229] Stalin had cautioned against this; he believed that nationalism would lead the Polish working-classes to support their government’s war effort.[229] He also believed that the Red Army was ill-prepared to conduct an offensive war and that it would give White Armies a chance to resurface in Crimea, potentially reigniting the civil war.[229] Stalin lost the argument, after which he accepted Lenin’s decision and supported it.[225] Along the Southwest Front, he became determined to conquer Lviv; in focusing on this goal he disobeyed orders in early August to transfer his troops to assist Mikhail Tukhachevsky‘s forces that were attacking Warsaw.[230]

In mid-August 1920, the Poles repulsed the Russian advance, and Stalin returned to Moscow to attend the Politburo meeting.[231] In Moscow, Lenin and Trotsky blamed him for his behavior in the Polish–Soviet war.[232] Stalin felt humiliated and under-appreciated; on 17 August, he demanded demission from the military, which was granted on 1 September.[233] At the 9th Bolshevik Conference in late September, Trotsky accused Stalin of “strategic mistakes” in his handling of the war.[234] Trotsky claimed that Stalin sabotaged the campaign by disobeying troop transfer orders.[235] Lenin joined Trotsky in criticising him, and nobody spoke on his behalf at the conference.[236] Stalin felt disgraced and increased his antipathy toward Trotsky.[217] The Polish-Soviet War ended on 18 March 1921, when a peace treaty was signed in Riga.[237]

Lenin’s final years: 1921–1923[edit source]

Stalin wearing a Order of the Red Banner. According to info published in Pravda (Pravda. 24 December 1939. No: 354 (8039)), this photograph was taken in Ordzhonikidze‘s house in 1921.

The Soviet government sought to bring neighbouring states under its domination; in February 1921 it invaded the Menshevik-governed Georgia,[238] while in April 1921, Stalin ordered the Red Army into Turkestan to reassert Russian state control.[239] As People’s Commissar for Nationalities, Stalin believed that each national and ethnic group should have the right to self-expression,[240] facilitated through “autonomous republics” within the Russian state in which they could oversee various regional affairs.[241] In taking this view, some Marxists accused him of bending too much to bourgeois nationalism, while others accused him of remaining too Russocentric by seeking to retain these nations within the Russian state.[240]

Stalin’s native Caucasus posed a particular problem because of its highly multi-ethnic mix.[242] Stalin opposed the idea of separate Georgian, Armenian, and Azerbaijani autonomous republics, arguing that these would likely oppress ethnic minorities within their respective territories; instead he called for a Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic.[243] The Georgian Communist Party opposed the idea, resulting in the Georgian affair.[244] In mid-1921, Stalin returned to the southern Caucasus, there calling on Georgian Communists to avoid the chauvinistic Georgian nationalism which marginalised the Abkhazian, Ossetian, and Adjarian minorities in Georgia.[245] On this trip, Stalin met with his son Yakov, and brought him back to Moscow;[246] Nadezhda had given birth to another of Stalin’s sons, Vasily, in March 1921.[246]

After the civil war, workers’ strikes and peasant uprisings broke out across Russia, largely in opposition to Sovnarkom’s food requisitioning project; as an antidote, Lenin introduced market-oriented reforms: the New Economic Policy (NEP).[247] There was also internal turmoil in the Communist Party, as Trotsky led a faction calling for abolition of trade unions; Lenin opposed this, and Stalin helped rally opposition to Trotsky’s position.[248] Stalin also agreed to supervise the Department of Agitation and Propaganda in the Central Committee Secretariat.[249] At the 11th Party Congress in 1922, Lenin nominated Stalin as the party’s new General Secretary. Although concerns were expressed that adopting this new post on top of his others would overstretch his workload and give him too much power, Stalin was appointed to the position.[250] For Lenin, it was advantageous to have a key ally in this crucial post.[251]

Stalin is too crude, and this defect which is entirely acceptable in our milieu and in relationships among us as communists, becomes unacceptable in the position of General Secretary. I therefore propose to comrades that they should devise a means of removing him from this job and should appoint to this job someone else who is distinguished from comrade Stalin in all other respects only by the single superior aspect that he should be more tolerant, more polite and more attentive towards comrades, less capricious, etc.

— Lenin’s Testament, 4 January 1923;[252] this was possibly composed by Krupskaya rather than Lenin himself.[253]Stalin (right) confers with an ailing Lenin at Gorky in September 1922

In May 1922, a massive stroke left Lenin partially paralyzed.[254] Residing at his Gorki dacha, Lenin’s main connection to Sovnarkom was through Stalin, who was a regular visitor.[255] Lenin twice asked Stalin to procure poison so that he could commit suicide, but Stalin never did so.[256] Despite this comradeship, Lenin disliked what he referred to as Stalin’s “Asiatic” manner and told his sister Maria that Stalin was “not intelligent”.[257] Lenin and Stalin argued on the issue of foreign trade; Lenin believed that the Soviet state should have a monopoly on foreign trade, but Stalin supported Grigori Sokolnikov‘s view that doing so was impractical at that stage.[258] Another disagreement came over the Georgian affair, with Lenin backing the Georgian Central Committee’s desire for a Georgian Soviet Republic over Stalin’s idea of a Transcaucasian one.[259]

They also disagreed on the nature of the Soviet state. Lenin called for establishment of a new federation named the “Union of Soviet Republics of Europe and Asia”, reflecting his desire for expansion across the two continents and insisted that the Russian state should join this union on equal terms with the other Soviet states.[260] Stalin believed this would encourage independence sentiment among non-Russians, instead arguing that ethnic minorities would be content as “autonomous republics” within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.[261] Lenin accused Stalin of “Great Russian chauvinism”; Stalin accused Lenin of “national liberalism”.[262] A compromise was reached, in which the federation would be renamed the “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics” (USSR).[260] The USSR’s formation was ratified in December 1922; although officially a federal system, all major decisions were taken by the governing Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in Moscow.[263]

Their differences also became personal; Lenin was particularly angered when Stalin was rude to his wife Krupskaya during a telephone conversation.[264] In the final years of his life, Krupskaya provided governing figures with Lenin’s Testament, a series of increasingly disparaging notes about Stalin. These criticised Stalin’s rude manners and excessive power, suggesting that Stalin should be removed from the position of general secretary.[265] Some historians have questioned whether Lenin ever produced these, suggesting instead that they may have been written by Krupskaya, who had personal differences with Stalin;[253] Stalin, however, never publicly voiced concerns about their authenticity.[266]

Consolidation of power[edit source]

Main article: Rise of Joseph Stalin

Succeeding Lenin: 1924–1927[edit source]

(From left to right) Stalin, Alexei Rykov, Lev Kamenev, and Grigori Zinoviev in 1925

Lenin died in January 1924.[267] Stalin took charge of the funeral and was one of its pallbearers; against the wishes of Lenin’s widow, the Politburo embalmed his corpse and placed it within a mausoleum in Moscow’s Red Square.[268] It was incorporated into a growing personality cult devoted to Lenin, with Petrograd being renamed “Leningrad” that year.[269] To bolster his image as a devoted Leninist, Stalin gave nine lectures at Sverdlov University on the “Foundations of Leninism“, later published in book form.[270] During the 13th Party Congress in May 1924, “Lenin’s Testament” was read only to the leaders of the provincial delegations.[271] Embarrassed by its contents, Stalin offered his resignation as General Secretary; this act of humility saved him and he was retained in the position.[272]

As General Secretary, Stalin had a free hand in making appointments to his own staff, implanting his loyalists throughout the party and administration.[273] Favouring new Communist Party members, many from worker and peasant backgrounds, to the “Old Bolsheviks” who tended to be university educated,[274] he ensured he had loyalists dispersed across the country’s regions.[275] Stalin had much contact with young party functionaries,[276] and the desire for promotion led many provincial figures to seek to impress Stalin and gain his favour.[277] Stalin also developed close relations with the trio at the heart of the secret police (first the Cheka and then its replacement, the State Political Directorate): Felix Dzerzhinsky, Genrikh Yagoda, and Vyacheslav Menzhinsky.[278] In his private life, he divided his time between his Kremlin apartment and a dacha at Zubalova;[279] his wife gave birth to a daughter, Svetlana, in February 1926.[280]

In the wake of Lenin’s death, various protagonists emerged in the struggle to become his successor: alongside Stalin was Trotsky, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, and Mikhail Tomsky.[281] Stalin saw Trotsky — whom he personally despised[282] — as the main obstacle to his dominance within the party.[283] While Lenin had been ill Stalin had forged an anti-Trotsky alliance with Kamenev and Zinoviev.[284] Although Zinoviev was concerned about Stalin’s growing authority, he rallied behind him at the 13th Congress as a counterweight to Trotsky, who now led a party faction known as the Left Opposition.[285] The Left Opposition believed the NEP conceded too much to capitalism; Stalin was called a “rightist” for his support of the policy.[286] Stalin built up a retinue of his supporters in the Central Committee,[287] while the Left Opposition were gradually removed from their positions of influence.[288] He was supported in this by Bukharin, who, like Stalin, believed that the Left Opposition’s proposals would plunge the Soviet Union into instability.[289]Stalin and his close associates Anastas Mikoyan and Sergo Ordzhonikidze in Tbilisi, 1925

In late 1924, Stalin moved against Kamenev and Zinoviev, removing their supporters from key positions.[290] In 1925, the two moved into open opposition to Stalin and Bukharin.[291] At the 14th Party Congress in December, they launched an attack against Stalin’s faction, but it was unsuccessful.[292] Stalin in turn accused Kamenev and Zinoviev of reintroducing factionalism — and thus instability — into the party.[292] In mid-1926, Kamenev and Zinoviev joined with Trotsky’s supporters to form the United Opposition against Stalin;[293] in October they agreed to stop factional activity under threat of expulsion, and later publicly recanted their views under Stalin’s command.[294] The factionalist arguments continued, with Stalin threatening to resign in October and then December 1926 and again in December 1927.[295] In October 1927, Zinoviev and Trotsky were removed from the Central Committee;[296] the latter was exiled to Kazakhstan and later deported from the country in 1929.[297] Some of those United Opposition members who were repentant were later rehabilitated and returned to government.[298]

Stalin was now the party’s supreme leader,[299] although he was not the head of government, a task he entrusted to his key ally Vyacheslav Molotov.[300] Other important supporters on the Politburo were Voroshilov, Lazar Kaganovich, and Sergo Ordzhonikidze,[301] with Stalin ensuring his allies ran the various state institutions.[302] According to Montefiore, at this point “Stalin was the leader of the oligarchs but he was far from a dictator”.[303] His growing influence was reflected in naming of various locations after him; in June 1924 the Ukrainian mining town of Yuzovka became Stalino,[304] and in April 1925, Tsaritsyn was renamed Stalingrad on the order of Mikhail Kalinin and Avel Enukidze.[305]

In 1926, Stalin published On Questions of Leninism.[306] Here, he argued for the concept of “Socialism in One Country“, which he presented as an orthodox Leninist perspective. It nevertheless clashed with established Bolshevik views that socialism could not be established in one country but could only be achieved globally through the process of world revolution.[306] In 1927, there was some argument in the party over Soviet policy regarding China. Stalin had called for the Chinese Communists to ally themselves with Kuomintang (KMT) nationalists, viewing a Communist-Kuomintang alliance as the best bulwark against Japanese imperial expansionism. Instead, the KMT repressed the Communists and a civil war broke out between the two sides.[307]

Dekulakisation, collectivisation, and industrialisation: 1927–1931[edit source]

Economic policy[edit source]

We have fallen behind the advanced countries by fifty to a hundred years. We must close that gap in ten years. Either we do this or we’ll be crushed.

This is what our obligations before the workers and peasants of the USSR dictate to us.

— Stalin, February 1931[308]

The Soviet Union lagged behind the industrial development of Western countries,[309] and there had been a shortfall of grain; 1927 produced only 70% of grain produced in 1926.[310] Stalin’s government feared attack from Japan, France, the United Kingdom, Poland, and Romania.[311] Many Communists, including in Komsomol, OGPU, and the Red Army, were eager to be rid of the NEP and its market-oriented approach;[312] they had concerns about those who profited from the policy: affluent peasants known as “kulaks” and small business owners or “Nepmen“.[313] At this point, Stalin turned against the NEP, which put him on a course to the “left” even of Trotsky or Zinoviev.[314]

In early 1928 Stalin travelled to Novosibirsk, where he alleged that kulaks were hoarding their grain and ordered that the kulaks be arrested and their grain confiscated, with Stalin bringing much of the area’s grain back to Moscow with him in February.[315] At his command, grain procurement squads surfaced across Western Siberia and the Urals, with violence breaking out between these squads and the peasantry.[316] Stalin announced that both kulaks and the “middle peasants” must be coerced into releasing their harvest.[317] Bukharin and several other Central Committee members were angry that they had not been consulted about this measure, which they deemed rash.[318] In January 1930, the Politburo approved the liquidation of the kulak class; accused kulaks were rounded up and exiled to other parts of the country or to concentration camps.[319] Large numbers died during the journey.[320] By July 1930, over 320,000 households had been affected by the de-kulakisation policy.[319] According to Stalin biographer Dmitri Volkogonov, de-kulakisation was “the first mass terror applied by Stalin in his own country.”[321]Aleksei Grigorievich Stakhanov with a fellow miner; Stalin’s government initiated the Stakhanovite movement to encourage hard work. It was partly responsible for a substantial rise in production during the 1930s.[322]

In 1929, the Politburo announced the mass collectivisation of agriculture,[323] establishing both kolkhozy collective farms and sovkhoz state farms.[324] Stalin barred kulaks from joining these collectives.[325] Although officially voluntary, many peasants joined the collectives out of fear they would face the fate of the kulaks; others joined amid intimidation and violence from party loyalists.[326] By 1932, about 62% of households involved in agriculture were part of collectives, and by 1936 this had risen to 90%.[327] Many of the collectivised peasants resented the loss of their private farmland,[328] and productivity slumped.[329] Famine broke out in many areas,[330] with the Politburo frequently ordering distribution of emergency food relief to these regions.[331]

Armed peasant uprisings against dekulakisation and collectivisation broke out in Ukraine, northern Caucasus, southern Russia, and central Asia, reaching their apex in March 1930; these were suppressed by the Red Army.[332] Stalin responded to the uprisings with an article insisting that collectivisation was voluntary and blaming any violence and other excesses on local officials.[333] Although he and Stalin had been close for many years,[334] Bukharin expressed concerns about these policies; he regarded them as a return to Lenin’s old “war communism” policy and believed that it would fail. By mid-1928 he was unable to rally sufficient support in the party to oppose the reforms.[335] In November 1929 Stalin removed him from the Politburo.[336]

Officially, the Soviet Union had replaced the “irrationality” and “wastefulness” of a market economy with a planned economy organised along a long-term, precise, and scientific framework; in reality, Soviet economics were based on ad hoc commandments issued from the centre, often to make short-term targets.[337] In 1928, the first five-year plan was launched, its main focus on boosting heavy industry;[338] it was finished a year ahead of schedule, in 1932.[339] The USSR underwent a massive economic transformation.[340] New mines were opened, new cities like Magnitogorsk constructed, and work on the White Sea-Baltic Canal began.[340] Millions of peasants moved to the cities, although urban house building could not keep up with the demand.[340] Large debts were accrued purchasing foreign-made machinery.[341]

Many of major construction projects, including the White Sea-Baltic Canal and the Moscow Metro, were constructed largely through forced labour.[342] The last elements of workers’ control over industry were removed, with factory managers increasing their authority and receiving privileges and perks;[343] Stalin defended wage disparity by pointing to Marx’s argument that it was necessary during the lower stages of socialism.[344] To promote intensification of labour, a series of medals and awards as well as the Stakhanovite movement were introduced.[322] Stalin’s message was that socialism was being established in the USSR while capitalism was crumbling amid the Wall Street crash.[345] His speeches and articles reflected his utopian vision of the Soviet Union rising to unparalleled heights of human development, creating a “new Soviet person“.[346]

Cultural and foreign policy[edit source]

In 1928, Stalin declared that class war between the proletariat and their enemies would intensify as socialism developed.[347] He warned of a “danger from the right”, including in the Communist Party itself.[348] The first major show trial in the USSR was the Shakhty Trial of 1928, in which several middle-class “industrial specialists” were convicted of sabotage.[349] From 1929 to 1930, further show trials were held to intimidate opposition:[350] these included the Industrial Party Trial, Menshevik Trial, and Metro-Vickers Trial.[351] Aware that the ethnic Russian majority may have concerns about being ruled by a Georgian,[352] he promoted ethnic Russians throughout the state hierarchy and made the Russian language compulsory throughout schools and offices, albeit to be used in tandem with local languages in areas with non-Russian majorities.[353] Nationalist sentiment among ethnic minorities was suppressed.[354] Conservative social policies were promoted to enhance social discipline and boost population growth; this included a focus on strong family units and motherhood, re-criminalisation of homosexuality, restrictions placed on abortion and divorce, and abolition of the Zhenotdel women’s department.[355]Photograph taken of the 1931 demolition of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow in order to make way for the Palace of the Soviets

Stalin desired a “cultural revolution“,[356] entailing both creation of a culture for the “masses” and wider dissemination of previously elite culture.[357] He oversaw proliferation of schools, newspapers, and libraries, as well as advancement of literacy and numeracy.[358] Socialist realism was promoted throughout arts,[359] while Stalin personally wooed prominent writers, namely Maxim Gorky, Mikhail Sholokhov, and Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy.[360] He also expressed patronage for scientists whose research fitted within his preconceived interpretation of Marxism; for instance, he endorsed research of an agrobiologist Trofim Lysenko despite the fact that it was rejected by the majority of Lysenko’s scientific peers as pseudo-scientific.[361] The government’s anti-religious campaign was re-intensified,[362] with increased funding given to the League of Militant Atheists.[354] Christian, Muslim, and Buddhist clergy faced persecution.[350] Many religious buildings were demolished, most notably Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, destroyed in 1931 to make way for the (never completed) Palace of the Soviets.[363] Religion retained an influence over much of the population; in the 1937 census, 57% of respondents identified as religious.[364]

Throughout the 1920s and beyond, Stalin placed a high priority on foreign policy.[365] He personally met with a range of Western visitors, including George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells, both of whom were impressed with him.[366] Through the Communist International, Stalin’s government exerted a strong influence over Marxist parties elsewhere in the world;[367] initially, Stalin left the running of the organisation largely to Bukharin.[368] At its 6th Congress in July 1928, Stalin informed delegates that the main threat to socialism came not from the right but from non-Marxist socialists and social democrats, whom he called “social fascists“;[369] Stalin recognised that in many countries, the social democrats were the Marxist-Leninists’ main rivals for working-class support.[370] This preoccupation with opposing rival leftists concerned Bukharin, who regarded the growth of fascism and the far right across Europe as a far greater threat.[368] After Bukharin’s departure, Stalin placed the Communist International under the administration of Dmitry Manuilsky and Osip Piatnitsky.[367]

Stalin faced problems in his family life. In 1929, his son Yakov unsuccessfully attempted suicide; his failure earned Stalin’s contempt.[371] His relationship with Nadezhda was also strained amid their arguments and her mental health problems.[372] In November 1932, after a group dinner in the Kremlin in which Stalin flirted with other women, Nadezhda shot herself.[373] Publicly, the cause of death was given as appendicitis; Stalin also concealed the real cause of death from his children.[374] Stalin’s friends noted that he underwent a significant change following her suicide, becoming emotionally harder.[375]

Major crises: 1932–1939[edit source]

Famine[edit source]

Further information: Soviet famine of 1932–33, Holodomor, and Kazakh famine of 1932–33Soviet famine of 1932–33. Areas of most disastrous famine marked with black.

Within the Soviet Union, there was widespread civic disgruntlement against Stalin’s government.[376] Social unrest, previously restricted largely to the countryside, was increasingly evident in urban areas, prompting Stalin to ease on some of his economic policies in 1932.[377] In May 1932, he introduced a system of kolkhoz markets where peasants could trade their surplus produce.[378] At the same time, penal sanctions became more severe; at Stalin’s instigation, in August 1932 a decree was introduced wherein the theft of even a handful of grain could be a capital offense.[379] The second five-year plan had its production quotas reduced from that of the first, with the main emphasis now being on improving living conditions.[377] It therefore emphasised the expansion of housing space and the production of consumer goods.[377] Like its predecessor, this plan was repeatedly amended to meet changing situations; there was for instance an increasing emphasis placed on armament production after Adolf Hitler became German chancellor in 1933.[380]

The Soviet Union experienced a major famine which peaked in the winter of 1932–33;[381] between five and seven million people died.[382] The worst affected areas were Ukraine and the North Caucasus, although the famine also affected Kazakhstan and several Russian provinces.[383] Historians have long debated whether Stalin’s government had intended the famine to occur or not;[384] there are no known documents in which Stalin or his government explicitly called for starvation to be used against the population.[385] The 1931 and 1932 harvests had been poor ones because of weather conditions[386] and had followed several years in which lower productivity had resulted in a gradual decline in output.[382] Government policies—including the focus on rapid industrialisation, the socialisation of livestock, and the emphasis on sown areas over crop rotation—exacerbated the problem;[387] the state had also failed to build reserve grain stocks for such an emergency.[388] Stalin blamed the famine on hostile elements and sabotage within the peasantry;[389] his government provided small amounts of food to famine-struck rural areas, although this was wholly insufficient to deal with the levels of starvation.[390] The Soviet government believed that food supplies should be prioritized for the urban workforce;[391] for Stalin, the fate of Soviet industrialisation was far more important than the lives of the peasantry.[392] Grain exports, which were a major means of Soviet payment for machinery, declined heavily.[390] Stalin would not acknowledge that his policies had contributed to the famine,[379] the existence of which was kept secret from foreign observers.[393]

Ideological and foreign affairs[edit source]

See also: Stalin’s cult of personality

In 1935–36, Stalin oversaw a new constitution; its dramatic liberal features were designed as propaganda weapons, for all power rested in the hands of Stalin and his Politburo.[394] He declared that “socialism, which is the first phase of communism, has basically been achieved in this country”.[394] In 1938, The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks), colloquially known as the Short Course, was released;[395] Conquest later referred to it as the “central text of Stalinism”.[396] A number of authorised Stalin biographies were also published,[397] although Stalin generally wanted to be portrayed as the embodiment of the Communist Party rather than have his life story explored.[398] During the later 1930s, Stalin placed “a few limits on the worship of his own greatness”.[398] By 1938, Stalin’s inner circle had gained a degree of stability, containing the personalities who would remain there until Stalin’s death.[399]Review of Soviet armored fighting vehicles used to equip the Republican People’s Army during the Spanish Civil War

Seeking improved international relations, in 1934 the Soviet Union secured membership of the League of Nations, of which it had previously been excluded.[400] Stalin initiated confidential communications with Hitler in October 1933, shortly after the latter came to power in Germany.[401] Stalin admired Hitler, particularly his manoeuvres to remove rivals within the Nazi Party in the Night of the Long Knives.[402] Stalin nevertheless recognised the threat posed by fascism and sought to establish better links with the liberal democracies of Western Europe;[403] in May 1935, the Soviets signed a treaty of mutual assistance with France and Czechoslovakia.[404] At the Communist International’s 7th Congress, held in July–August 1935, the Soviet government encouraged Marxist-Leninists to unite with other leftists as part of a popular front against fascism.[405] In turn, the anti-communist governments of Germany, Fascist Italy and Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1936.[406]

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936, the Soviets sent 648 aircraft and 407 tanks to the left-wing Republican faction; these were accompanied by 3,000 Soviet troops and 42,000 members of the International Brigades set up by the Communist International.[407] Stalin took a strong personal involvement in the Spanish situation.[408] Germany and Italy backed the Nationalist faction, which was ultimately victorious in March 1939.[409] With the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in July 1937, the Soviet Union and China signed a non-aggression pact the following August.[410] Stalin aided the Chinese as the KMT and the Communists had suspended their civil war and formed the desired United Front.[411]

The Great Terror[edit source]

Exhumed mass grave of the Vinnytsia massacre

Stalin often gave conflicting signals regarding state repression.[412] In May 1933, he released from prison many convicted of minor offenses, ordering the security services not to enact further mass arrests and deportations.[413] In September 1934, he launched a commission to investigate false imprisonments; that same month he called for the execution of workers at the Stalin Metallurgical Factory accused of spying for Japan.[412] This mixed approach began to change in December 1934, after prominent party member Sergey Kirov was murdered.[414] After the murder, Stalin became increasingly concerned by the threat of assassination, improved his personal security, and rarely went out in public.[415] State repression intensified after Kirov’s death;[416] Stalin instigated this, reflecting his prioritisation of security above other considerations.[417] Stalin issued a decree establishing NKVD troikas which could mete out rulings without involving the courts.[418] In 1935, he ordered the NKVD to expel suspected counter-revolutionaries from urban areas;[380] in early 1935, over 11,000 were expelled from Leningrad.[380] In 1936, Nikolai Yezhov became head of the NKVD.[419]

Stalin orchestrated the arrest of many former opponents in the Communist Party as well as sitting members of the Central Committee: denounced as Western-backed mercenaries, many were imprisoned or exiled internally.[420] The first Moscow Trial took place in August 1936; Kamenev and Zinoviev were among those accused of plotting assassinations, found guilty in a show trial, and executed.[421] The second Moscow Show Trial took place in January 1937,[422] and the third in March 1938, in which Bukharin and Rykov were accused of involvement in the alleged Trotskyite-Zinovievite terrorist plot and sentenced to death.[423] By late 1937, all remnants of collective leadership were gone from the Politburo, which was controlled entirely by Stalin.[424] There were mass expulsions from the party,[425] with Stalin commanding foreign communist parties to also purge anti-Stalinist elements.[426]Victims of Stalin’s Great Terror in the Bykivnia mass graves

Repressions further intensified in December 1936 and remained at a high level until November 1938, a period known as the Great Purge.[417] By the latter part of 1937, the purges had moved beyond the party and were affecting the wider population.[427] In July 1937, the Politburo ordered a purge of “anti-Soviet elements” in society, targeting anti-Stalin Bolsheviks, former Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, priests, ex-White Army soldiers, and common criminals.[428] That month, Stalin and Yezhov signed Order No. 00447, listing 268,950 people for arrest, of whom 75,950 were executed.[429] He also initiated “national operations”, the ethnic cleansing of non-Soviet ethnic groups—among them Poles, Germans, Latvians, Finns, Greeks, Koreans, and Chinese—through internal or external exile.[430] During these years, approximately 1.6 million people were arrested,[431] 700,000 were shot, and an unknown number died under NKVD torture.[431]

During the 1930s and 1940s, NKVD groups assassinated defectors and opponents abroad;[432] in August 1940, Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico, eliminating the last of Stalin’s opponents among the former Party leadership.[433] In May, this was followed by the arrest of most members of the military Supreme Command and mass arrests throughout the military, often on fabricated charges.[434] These purges replaced most of the party’s old guard with younger officials who did not remember a time before Stalin’s leadership and who were regarded as more personally loyal to him.[435] Party functionaries readily carried out their commands and sought to ingratiate themselves with Stalin to avoid becoming the victim of the purge.[436] Such functionaries often carried out a greater number of arrests and executions than their quotas set by Stalin’s central government.[437]

Stalin initiated all key decisions during the Terror, personally directing many of its operations and taking an interest in their implementation.[438] His motives in doing so have been much debated by historians.[431] His personal writings from the period were — according to Khlevniuk — “unusually convoluted and incoherent”, filled with claims about enemies encircling him.[439] He was particularly concerned at the success that right-wing forces had in overthrowing the leftist Spanish government,[440] fearing a domestic fifth column in the event of future war with Japan and Germany.[441] The Great Terror ended when Yezhov was removed as the head of the NKVD, to be replaced by Lavrentiy Beria,[442] a man totally devoted to Stalin.[443] Yezhov was arrested in April 1939 and executed in 1940.[444] The Terror damaged the Soviet Union’s reputation abroad, particularly among sympathetic leftists.[445] As it wound down, Stalin sought to deflect responsibility from himself,[446] blaming its “excesses” and “violations of law” on Yezhov.[447] According to historian James Harris, contemporary archival research shows that the motivation behind the purges was not Stalin attempting to establish his own personal dictatorship; evidence suggests he was committed to building the socialist state envisioned by Lenin. The real motivation for the terror, according to Harris, was an excessive fear of counterrevolution.[448]

World War II[edit source]

Main article: Soviet Union in World War II

Pact with Nazi Germany: 1939–1941[edit source]

As a Marxist–Leninist, Stalin expected an inevitable conflict between competing capitalist powers; after Nazi Germany annexed Austria and then part of Czechoslovakia in 1938, Stalin recognised a war was looming.[449] He sought to maintain Soviet neutrality, hoping that a German war against France and Britain would lead to Soviet dominance in Europe.[450] Militarily, the Soviets also faced a threat from the east, with Soviet troops clashing with the expansionist Japanese in the latter part of the 1930s.[451] Stalin initiated a military build-up, with the Red Army more than doubling between January 1939 and June 1941, although in its haste to expand many of its officers were poorly trained.[452] Between 1940 and 1941 he also purged the military, leaving it with a severe shortage of trained officers when war broke out.[453]Stalin greeting the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop in the Kremlin, 1939

As Britain and France seemed unwilling to commit to an alliance with the Soviet Union, Stalin saw a better deal with the Germans.[454] On 3 May 1939, Stalin replaced his western-oriented foreign minister Maxim Litvinov with Vyacheslav Molotov.[455] In May 1939, Germany began negotiations with the Soviets, proposing that Eastern Europe be divided between the two powers.[456] Stalin saw this as an opportunity both for territorial expansion and temporary peace with Germany.[457] In August 1939, the Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact with Germany, a non-aggression pact negotiated by Molotov and German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop.[458] A week later, Germany invaded Poland, sparking the UK and France to declare war on Germany.[459] On 17 September, the Red Army entered eastern Poland, officially to restore order amid the collapse of the Polish state.[460] On 28 September, Germany and the Soviet Union exchanged some of their newly conquered territories; Germany gained the linguistically Polish-dominated areas of Lublin Province and part of Warsaw Province while the Soviets gained Lithuania.[461] A German–Soviet Frontier Treaty was signed shortly after, in Stalin’s presence.[462] The two states continued trading, undermining the British blockade of Germany.[463]

The Soviets further demanded parts of eastern Finland, but the Finnish government refused. The Soviets invaded Finland in November 1939, yet despite numerical inferiority, the Finns kept the Red Army at bay.[464] International opinion backed Finland, with the Soviets being expelled from the League of Nations.[465] Embarrassed by their inability to defeat the Finns, the Soviets signed an interim peace treaty, in which they received territorial concessions from Finland.[466] In June 1940, the Red Army occupied the Baltic states, which were forcibly merged into the Soviet Union in August;[467] they also invaded and annexed Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, parts of Romania.[468] The Soviets sought to forestall dissent in these new East European territories with mass repressions.[469] One of the most noted instances was the Katyn massacre of April and May 1940, in which around 22,000 members of the Polish armed forces, police, and intelligentsia were executed.[470]

The speed of the German victory over and occupation of France in mid-1940 took Stalin by surprise.[471] He increasingly focused on appeasement with the Germans to delay any conflict with them.[472] After the Tripartite Pact was signed by Axis Powers Germany, Japan, and Italy in October 1940, Stalin proposed that the USSR also join the Axis alliance.[473] To demonstrate peaceful intentions toward Germany, in April 1941 the Soviets signed a neutrality pact with Japan.[474] Although de facto head of government for a decade and a half, Stalin concluded that relations with Germany had deteriorated to such an extent that he needed to deal with the problem as de jure head of government as well: on 6 May, Stalin replaced Molotov as Premier of the Soviet Union.[475]

German invasion: 1941–1942[edit source]

With all the men at the front, women dig anti-tank trenches around Moscow in 1941

In June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union, initiating the war on the Eastern Front.[476] Although intelligence agencies had repeatedly warned him of Germany’s intentions, Stalin was taken by surprise.[477] He formed a State Defense Committee, which he headed as Supreme Commander,[478] as well as a military Supreme Command (Stavka),[479] with Georgy Zhukov as its Chief of Staff.[480] The German tactic of blitzkrieg was initially highly effective; the Soviet air force in the western borderlands was destroyed within two days.[481] The German Wehrmacht pushed deep into Soviet territory;[482] soon, Ukraine, Byelorussia, and the Baltic states were under German occupation, and Leningrad was under siege;[483] and Soviet refugees were flooding into Moscow and surrounding cities.[484] By July, Germany’s Luftwaffe was bombing Moscow,[483] and by October the Wehrmacht was amassing for a full assault on the capital. Plans were made for the Soviet government to evacuate to Kuibyshev, although Stalin decided to remain in Moscow, believing his flight would damage troop morale.[485] The German advance on Moscow was halted after two months of battle in increasingly harsh weather conditions.[486]

Going against the advice of Zhukov and other generals, Stalin emphasised attack over defence.[487] In June 1941, he ordered a scorched earth policy of destroying infrastructure and food supplies before the Germans could seize them,[488] also commanding the NKVD to kill around 100,000 political prisoners in areas the Wehrmacht approached.[489] He purged the military command; several high-ranking figures were demoted or reassigned and others were arrested and executed.[490] With Order No. 270, Stalin commanded soldiers risking capture to fight to the death describing the captured as traitors;[491] among those taken as a prisoner of war by the Germans was Stalin’s son Yakov, who died in their custody.[492] Stalin issued Order No. 227 in July 1942, which directed that those retreating unauthorised would be placed in “penal battalions” used as cannon fodder on the front lines.[493] Amid the fighting, both the German and Soviet armies disregarded the law of war set forth in the Geneva Conventions;[494] the Soviets heavily publicised Nazi massacres of communists, Jews, and Romani.[495] Stalin exploited Nazi anti-Semitism, and in April 1942 he sponsored the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC) to garner Jewish and foreign support for the Soviet war effort.[496]The center of Stalingrad after liberation, 2 February 1943

The Soviets allied with the United Kingdom and United States;[497] although the U.S. joined the war against Germany in 1941, little direct American assistance reached the Soviets until late 1942.[494] Responding to the invasion, the Soviets intensified their industrial enterprises in central Russia, focusing almost entirely on production for the military.[498] They achieved high levels of industrial productivity, outstripping that of Germany.[495] During the war, Stalin was more tolerant of the Russian Orthodox Church, allowing it to resume some of its activities and meeting with Patriarch Sergius in September 1943.[499] He also permitted a wider range of cultural expression, notably permitting formerly suppressed writers and artists like Anna Akhmatova and Dmitri Shostakovich to disperse their work more widely.[500] The Internationale was dropped as the country’s national anthem, to be replaced with a more patriotic song.[501] The government increasingly promoted Pan-Slavist sentiment,[502] while encouraging increased criticism of cosmopolitanism, particularly the idea of “rootless cosmopolitanism”, an approach with particular repercussions for Soviet Jews.[503] Comintern was dissolved in 1943,[504] and Stalin encouraged foreign Marxist–Leninist parties to emphasise nationalism over internationalism to broaden their domestic appeal.[502]

In April 1942, Stalin overrode Stavka by ordering the Soviets’ first serious counter-attack, an attempt to seize German-held Kharkov in eastern Ukraine. This attack proved unsuccessful.[505] That year, Hitler shifted his primary goal from an overall victory on the Eastern Front, to the goal of securing the oil fields in the southern Soviet Union crucial to a long-term German war effort.[506] While Red Army generals saw evidence that Hitler would shift efforts south, Stalin considered this to be a flanking move in a renewed effort to take Moscow.[507] In June 1942, the German Army began a major offensive in Southern Russia, threatening Stalingrad; Stalin ordered the Red Army to hold the city at all costs.[508] This resulted in the protracted Battle of Stalingrad.[509] In December 1942, he placed Konstantin Rokossovski in charge of holding the city.[510] In February 1943, the German troops attacking Stalingrad surrendered.[511] The Soviet victory there marked a major turning point in the war;[512] in commemoration, Stalin declared himself Marshal of the Soviet Union.[513][514]

Soviet counter-attack: 1942–1945[edit source]

The Big Three: Stalin, U.S. PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt, and British Prime MinisterWinston Churchill at the Tehran Conference, November 1943

By November 1942, the Soviets had begun to repulse the important German strategic southern campaign and, although there were 2.5 million Soviet casualties in that effort, it permitted the Soviets to take the offensive for most of the rest of the war on the Eastern Front.[515] Germany attempted an encirclement attack at Kursk, which was successfully repulsed by the Soviets.[516] By the end of 1943, the Soviets occupied half of the territory taken by the Germans from 1941 to 1942.[517] Soviet military industrial output also had increased substantially from late 1941 to early 1943 after Stalin had moved factories well to the east of the front, safe from German invasion and aerial assault.[518]

In Allied countries, Stalin was increasingly depicted in a positive light over the course of the war.[519] In 1941, the London Philharmonic Orchestra performed a concert to celebrate his birthday,[520] and in 1942, Time magazine named him “Man of the Year“.[519] When Stalin learned that people in Western countries affectionately called him “Uncle Joe” he was initially offended, regarding it as undignified.[521] There remained mutual suspicions between Stalin, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who were together known as the “Big Three”.[522] Churchill flew to Moscow to visit Stalin in August 1942 and again in October 1944.[523] Stalin scarcely left Moscow throughout the war,[524] with Roosevelt and Churchill frustrated with his reluctance to travel to meet them.[525]

In November 1943, Stalin met with Churchill and Roosevelt in Tehran, a location of Stalin’s choosing.[526] There, Stalin and Roosevelt got on well, with both desiring the post-war dismantling of the British Empire.[527] At Tehran, the trio agreed that to prevent Germany rising to military prowess yet again, the German state should be broken up.[528] Roosevelt and Churchill also agreed to Stalin’s demand that the German city of Königsberg be declared Soviet territory.[528] Stalin was impatient for the UK and U.S. to open up a Western Front to take the pressure off of the East; they eventually did so in mid-1944.[529] Stalin insisted that, after the war, the Soviet Union should incorporate the portions of Poland it occupied pursuant to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Germany, which Churchill opposed.[530] Discussing the fate of the Balkans, later in 1944 Churchill agreed to Stalin’s suggestion that after the war, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and Yugoslavia would come under the Soviet sphere of influence while Greece would come under that of the West.[531]Soviet soldiers in Polotsk, 4 July 1944

In 1944, the Soviet Union made significant advances across Eastern Europe toward Germany,[532] including Operation Bagration, a massive offensive in the Byelorussian SSR against the German Army Group Centre.[533] In 1944 the German armies were pushed out of the Baltic states (with the exception of the Ostland), which were then re-annexed into the Soviet Union.[534] As the Red Army reconquered the Caucasus and Crimea, various ethnic groups living in the region—the Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingushi, Karachai, Balkars, and Crimean Tatars—were accused of having collaborated with the Germans. Using the idea of collective responsibility as a basis, Stalin’s government abolished their autonomous republics and between late 1943 and 1944 deported the majority of their populations to Central Asia and Siberia.[535] Over one million people were deported as a result of the policy.[536]